The 'Dialogues on Indigenous Peoples' Territories: Stories of Resilience' were launched on February 17, 2022.

The dialogues are created by Doctoral Candidate Luisa Castaneda-Quintana, in collaboration with Doctoral Candidate Giusto Amedeo Boccheni, the Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism and the Indigenous Law Association / Association du Droit Autochtone (ILADA).

The Dialogues are an initiative to start conversations on Indigenous Peoples, their realities, endeavours, and positive contributions to issues of global concern. The objective is to involve students, scholars, the faculty, civil society, and the larger public in meaningful discussions to foster theoretical and practical engagement to advance Indigenous Peoples' rights.

March 16, 2023, Indigenous Peoples in Africa, Challenges and Complexities

The sixth session of the dialogue was held online on March 16, 2023. The event featured guest speaker Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim and Vital Bambanze, members of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, in conversation with the coordinator of the Dialogues, Luisa Castaneda-Quintana.

More than 130 people connected from different countries, including Chad, Burundi, South Africa, Colombia, Russia, Ghana, Kenya, the Philippines, Cameroon, Australia, France, Honduras, Myanmar, the United States, Italy, Morocco, Canada, Zimbabwe, Gabon, Niger, Uganda, Rwanda, Liberia, India, Republic Democratic of Congo, Switzerland, and others.

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim and Vital Bambanze touched upon several key themes in their discussion. These included: colonial history and its legacy, the weaponization of the label “Indigenous,” the impacts of climate change on Indigenous Peoples, the role of Transnational Corporations in these issues and lastly, how change can come about.

They began by laying out the current and complex state of affairs for Indigenous Peoples in Africa. Ms. Ibrahim explained how Indigenous Peoples are defined under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples can be very different to how Indigenous Peoples from Africa define themselves. These categories, labels and definitions can be used to further marginalize the very people they are meant to protect. Mr. Bambanze emphasized that these are tactics used by administrative authorities to suppress Indigenous Peoples. Ms. Ibrahim outlined the significant work that was done to settle on the criteria used to define who is Indigenous. What came out of that work were 2 major criteria: 1. You need communities that can self-identity 2. You need connection to land. Ms. Ibrahim called for more laws to protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples at the national level. Foreign corporations have been worsening the situation of Indigenous Peoples by forcing them to leave their traditional territories (Mr. Bambanze). Ms. Ibrahim mentioned the lack of restrictions placed on Transnational Corporations in many of the African countries’ constitutions thus allowing foreign corporations or rich persons to grab the land in this way, especially premium land such as those near water - they occupy the land. And this occupation does not come about through free, prior, informed and consent.

Both speakers emphasized the serious impacts climate change has had on Indigenous Peoples, especially since they are the most vulnerable communities because of their livelihoods, connections to the land and loss of lands due to migrants (e.g. Lake Chad has lost 90% of its water according to Ms. Ibrahim). Tensions are also arising between Indigenous Peoples (e.g. pastoralists) and local farmers resulting from climate change migrations. Environmental degradation (due to monoculture, deforestation) and climate change are creating security, food and other crises. But both emphasized that Indigenous Peoples at the local level are also the ones spearheading adaptation and changes using traditional knowledge, by combining traditional and scientific research and working collaboratively. In essence, change is possible. Not only legislatively but also hopefully through vertical levels of governments in order to ensure lasting solutions (Mr. Bambanze). Direct access funding opportunities for Indigenous Peoples is one way of exercising change by enabling them to build their own way of development and to protect resources (Ms. Ibrahim). But we must ensure the money goes to them directly as it often gets lost along the way in administration and overhead. Lastly, for Mr. Bambanze, when we are asking for our rights as Indigenous Peoples (to practice our culture, protections for those rights) we are simply asking for the rights which we naturally and inherently have, we want those rights respected. Whose rights were threatened by the imposition of European ways of life on Indigenous Peoples and the territorial tensions created by the European colonial powers’ arbitrary division of Africa. We need to recognize the reparations Indigenous Peoples are due for their lost ways of life and lands. For Mr. Bambanze, human rights are also a matter of political evolution with Indigenous Peoples uniting against the white settlers, leading to self-determination took on a revolutionary dimension with the departure of the whites.

Watch the full recording of the sixth dialogue:

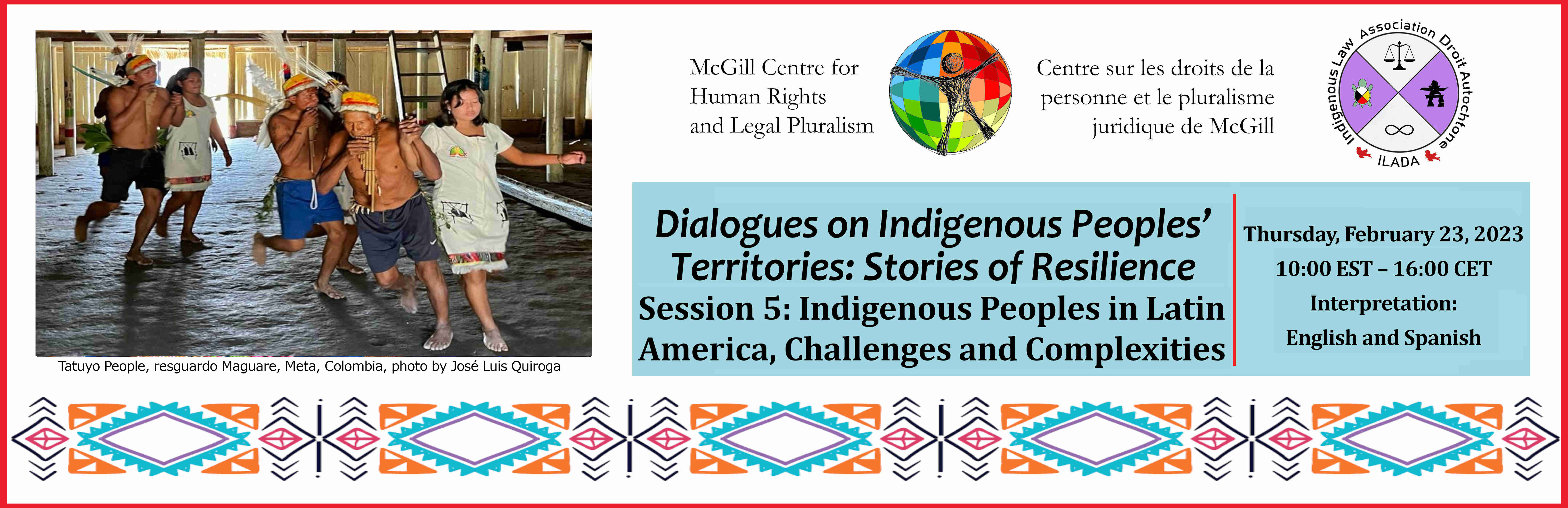

February 23, 2023: Indigenous Peoples in Latin America, Challenges and Complexities

The fifth session of the dialogue, titled “Indigenous Peoples in Latin America, Challenges and Complexities” was hosted virtually on February 23rd, 2023. The event featured a discussion with Dario Mejia Montalvo, Chair of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, in conversation with the coordinator of the Dialogues, Luisa Castaneda-Quintana.

More than 150 people connected from different countries, including Panama, Argentina, Chile, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Peru, Ecuador, Costa Rica, el Salvador, Bolivia, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, the United States, Canada, Kenya, Burundi, India, Italy, France and others.

Dario began his talk by sharing stories of his childhood and early understandings of Indigenous Peoples’ identity. He discussed how not understanding why his people needed to fight for their land has guided his work and the central question of what does it mean to recover land. Dario discussed the role of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues as a mechanism for Indigenous Peoples to communicate with states with their own voices and at the same level. Dario highlighted the centrality of Indigenous Peoples’ lands, societies, and peoples in economic, climate, and development issues worldwide.

In reflection on the role of Indigenous Peoples at COP26 and COP15, Dario reminded us that Indigenous Peoples are not a divisible "sector" or "industry" in the same way that one might compartmentalize health, education, or the environment. Indigenous Peoples are distinct and complete within their own societal logic and order. Colonial political projects such as class struggle are built around divisions from a societal order that is distinct and not necessarily applicable to Indigenous Peoples. Building on this point to answer more directly the question of the role of Indigenous Peoples at COP15 and COP26, Dario emphasized that societal and cultural diversity is critical to protecting biodiversity, especially since the division between climate and culture is based on societal norms and is non-existent to many Indigenous Peoples. At large, the COP conferences were largely closed to Indigenous peoples. The negotiation rooms were limited to state entities and large corporations. Dario blamed this failure on a refusal to work with Indigenous Peoples on their own terms, and a focus on procedural hurdles when discussing returning land or enacting Indigenous Peoples’ rights. The way forward is for Indigenous Peoples to demand autonomy over environmental decisions and the resources needed to enforce those decisions.

In response to follow-up questions Dario provided a few more insights. First, discussing the need for a joint dialogue tool at a regional level in Latin America to push for further enactment of the rights promised by United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Next, the importance of providing sufficient digital services to Indigenous Peoples, particularly in the area of translation and transmission of legal rights and information. Lastly, on the role of Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and the need to better protect Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge within Intellectual Property law frameworks.

This conversation with Dario provided an important window into the role of Indigenous Peoples on the International stage, and the practical fight for Indigenous Peoples’ rights being pushed through the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Dario highlighted the importance of recognizing the distinct nature of Indigenous Peoples, but also how Indigenous Peoples can and must work within imperfect institutions to pursue their rights, even when faced with resistance from colonial political and state actors.

Watch the full recording of the fifth dialogue:

November 23, 2022: State of realization of the rights to safe drinking water and sanitation for Indigenous Peoples

The fourth session of the Dialogue was held hybrid on November 23rd, 2022. The fourth session’s theme was “State of realization of the rights of safe drinking water and sanitation for Indigenous Peoples.” The event featured guest speaker Pedro Arrojo-Agudo, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Water and Sanitation, in conversation with the coordinator of the Dialogues, Luisa Castaneda-Quintana presented his recent report about the state of realization of the right to safe drinking water and sanitation for Indigenous Peoples, addressing the constraints and failures in the fulfilment of these rights.

More than 85 people connected from different countries, including India, Cambodia, Burundi, Colombia, Venezuela, Nepal, Cameroon, Canada, The United States of America, Kenya, Nicaragua, Honduras, Tanzania, Pakistan, Morocco, México, Chile, Brazil.

Mr. Arrojo-Agudo began by recognizing the sustainable practices of Indigenous Peoples that have been used for millenia. Unfortunately, climate change as well as extractivist projects have disrupted those practices. Now water that used to be safe, clean and protected is polluted. Mr. Arrojo-Agudo emphasized the notion of accessibility and noted that Indigenous Peoples’ territories tend to be situated in disadvantaged areas, which are far from public services. Affordability is another important concept to consider in this context, especially considering Indigenous Peoples represent 19% of the poorest people worldwide. Furthermore, he mentioned that it is often women who take on the responsibility of traveling to get access to water. Indigenous Women have to travel greater distances to access water, thus requiring more time, which encroaches on their studies and leisure time. Because of these long distances, they are also more vulnerable to gender-based violence. In his report, Mr. Arrojo-Agudo acknowledges the crucial role Indigenous Women play as wardens and protectors of water in their communities. They are holders and sharers of traditional water knowledge.

The third concept introduced by Mr. Arrojo-Agudo is acceptability. He pointed to a lack of intercultural approaches and disrespect for Indigenous Peoples’ worldviews and beliefs as reasons why some projects have been abandoned or not accepted by Indigenous Peoples’ communities. A cultural dialogue is crucial, despite the many differences between Indigenous Peoples’ approaches and Eurocentric values. People must take the time to listen and learn from Indigenous Peoples if fruitful and mutually beneficial work is to be done together. Indigenous Peoples’ approaches are holistic, with an inherent sacred respect for wetlands, rivers, lakes, etc. Water is interconnected and part of Indigenous Peoples’ cosmovisions. Water in this sense embodies a way of life, as well as life itself. He also stressed that Indigenous Peoples have the right to use their territories as they wish, in line with the Declaration of the United Nations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). For Mr. Arrojo-Agudo, states have an obligation to recognize the rights of Indigenous Peoples and to ensure compliance with the UNDRIP. They must respect the self-determination and authority of Indigenous Peoples. Moreover, they must adhere to free, prior and informed consent in the case of projects on Indigenous Peoples’ territories. There are many challenges and obstacles to this, and Mr. Arrojo-Agudo denounced the criminalization of community leaders and social movements.

For Mr. Arrojo-Agudo, we can learn many lessons from Indigenous Peoples, such as how to tackle climate change, sustainable management of aquatic ecosystems and democratic governance of safe drinking water and sanitation. Those lessons should be valued and recognized. Instead of being seen as a commodity, Mr. Arrojo-Agudo argues that water should be considered a common good. Furthermore, water should be for everybody and should not be owned. Mr Arrojo-Agudo calls for a human rights approach to water management. For him, understanding lakes or wetlands as sacred spaces offers us a genuine expression of sustainability and an integrated system of biodiversity. The emergence of a sustainability paradigm requires us to see rivers and ecosystems as living beings. In conclusion, Mr. Arrojo-Agudo emphasized that having access to affordable and accessible water should be a human right, and not a commodity.

Watch the full recording of the fourth dialogue:

October 6, 2022: Indigenous Peoples in Asia: Challenges and Complexities

The third session of the Dialogues was held on October 6th, 2022. The theme of session three was “Indigenous Peoples in Asia: Challenges and Complexities”. The event featured guest speaker Dr. Kundan Kumar, Indigenous Peoples and Resources and Climate Change expert, in conversation with the coordinator of the Dialogues, Luisa Castaneda-Quintana.

Dr. Kumar began by discussing how Indigenous people are generally treated in Asia and the status of recognition of Indigenous peoples in the region. He pointed out that there are similarities in the ways Indigenous peoples have been treated in Asian countries. Dr. Kumar noted that each nation is affected by a complex history of processes which have affected Indigenous peoples’ systems and societies. In particular, Dr. Kumar explained that in many cases, government policies were put into place which appropriated Indigenous lands and territories to the state. Dr. Kumar also touched on processes of assimilation and the breaking down of customary systems of governance. Dr. Kumar shared that while many countries in Asia do not recognize Indigenous peoples, there are strong movements for Indigenous recognition in the countries where these movements are allowed to survive.

Dr. Kumar also discussed the issue of recognition of Indigenous lands and territories. He explained that the situation in each country is complex and depends on the specific legal systems and politics. In some countries, protections are provided under the law or constitution and territories have thus been respected to a certain extent. However, Dr. Kumar noted that much land has been allotted to private companies, resulting in displacement and criminalization of the daily lives of Indigenous peoples.

Dr. Kumar further discussed the impact of climate change on Indigenous peoples in Asia, and the role of Indigenous peoples in mitigating climate change. Dr. Kumar raised the issue that climate mitigation efforts are often highly land intensive (for example, solar or hydro power projects). He noted that when Indigenous people and their lands are not recognized, their lands may be appropriated for climate mitigation projects. In particular, forest conservation has caused trouble for Indigenous peoples, whose presence and lives on the land become criminalized. As a result, Dr. Kumar stated that climate mitigation projects have joined mining and resource extraction as a major threat to Indigenous peoples’ lands. Dr. Kumar pointed out that for the most part, Indigenous people have not been given any agency or role in climate mitigation in Asia, despite the fact that Indigenous management of the land is a strong potential climate solution.

Watch the full recording of the third dialogue:

March 31, 2022: Challenging Scientific Hierarchies through Indigenous Peoples' Knowledge

On March 31, 2022, the Second Dialogue on Challenging Scientific Hierarchies through Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge was held with the special guest Tania Martínez-Cruz, an Indigenous Ëyuujk woman, scientist and interdisciplinary researcher, Member of the Global Hub on Indigenous Peoples Food Systems and Research Associate at Free University of Brussels. Around 120 people connected from different parts of the world. In conversation with Luisa Castaneda-Quintana, McGill Doctoral Candidate, Tania Martínez-Cruz shared stories of resilience where Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge has been crucial to ensuring the preservation of biodiversity and cosmovision and providing food and medicine for millions of people for centuries. She started the conversation by sharing her story when realizing she was and Indigenous woman and how that influenced her to become a scientist. She also mentioned how the educational system challenged her Indigenous knowledge and positionality as an Indigenous woman during her academic career and how she has reconciled with that.

Among other topics, Tania Martínez-Cruz highlighted the key role of Indigenous women in passing down the knowledge and the importance of language in this process. She noted and shared some experiences on how Indigenous Peoples' knowledge, territorial management practices, and food systems are vital to mitigate climate change and combat food insecurity. The second dialogue, in part, was based on the comment published in food nature by the Global-Hub on Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems titled “Rethinking hierarchies of evidence for sustainable food system”. We noted how dominant scientific knowledge is prominent while Indigenous Peoples' knowledge is disregarded as unscientific or less scientific and continues to be marginalized in policy and practice. Nevertheless, recognizing Indigenous Peoples' traditional knowledge systems as valuable is not new. There is a long acknowledgement that Indigenous Peoples are well-placed to provide expert contributions to global debates. They are informing global processes such as climate change, biodiversity and conservation. Yet, they are not part of the tables where decisions are made as expected. There's a troubling tokenistic aspect, almost like ticking a box, to including Indigenous Peoples' knowledge. The recognition of Indigenous Peoples' traditional knowledge systems as valuable is not about denying the value of scientific interventions but shifting hierarchies of power and knowledge. In this regard, the co-production of knowledge to generate context-specific knowledge is vital. There is a need to democratize science and recognize multiple ways of knowing. In this context, the Global-Hub on Indigenous Peoples' Food Systems serves as a channel to rethink dominant hierarchies of knowledge and then co-create and exchange knowledge that informs policymakers.

Watch the full recording of the second dialogue:

February 17, 2022: Indigenous Peoples and Global Challenges

For Session One on Indigenous Peoples & Global Challenges, we had a special guest, Anne Nuorgam, a Sámi woman, a long-term politician and a lawyer, and chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII).

During the launch, around 140 people connected from different parts of the world. Professor Frederic Megret, Co-Director of McGill's Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism and Simon Filiatrault, Co-President of the Indigenous Law association – ILADA, gave opening remarks. They acknowledged the traditional territory of the Kanien'kehà:ka and highlighted the importance of these dialogues to advance the respect of Indigenous Peoples' rights.

In conversation with Luisa Castaneda-Quintana, Anne Nuorgam started by sharing her story of realizing she was an Indigenous person and a Sámi woman and the importance of the language and education in the process. She talked about the global challenges that Indigenous Peoples face, such as lack of recognition of the existence of Indigenous Peoples by governments, lack of rights enforcement, lack of participation, climate change, and criminalization, among others. She noted that even though Indigenous Peoples live in more than 90 countries, their rights are not recognized in all of these countries. It is deeply unfortunate that many Indigenous Peoples are not recognized as such by governments on the continents of Asia and Africa. In this regard, she commented on the efforts of the UNPFII to advance the recognition of Indigenous Peoples' rights. We also discussed the criminalization of Indigenous Peoples. The State depicts indigenous Peoples who are defenders of their land and environment as "criminals". This has been a growing issue during the last few years. Some of the factors that have triggered increased violence, criminalization, and killing of Indigenous Peoples are the lack of land tenure rights and the pressures from illegal logging, mining, and general extraction of natural resources.

We concluded the session with a question regarding legal education, particularly in the role of law schools and Indigenous and non-Indigenous students to contribute to advancing the recognition and realization of Indigenous Peoples' rights.

Watch the full recording of the first dialogue: