In 1999, at the tender age of 18, Craig Buntin boarded an airplane in Kelowna, BC. His destination: Montreal. His purpose: to find the necessary coaching that would help him reach his dream of going to the Olympic games as a figure skater. He had a one-way ticket, and enough savings to keep him going for a couple of months. If it didn’t pan out, he would be hitching a ride home.

It was a bold, risky, and strategic move that ultimately paid off. Seven years later, and after having won the Canadian national championship, Buntin represented Canada as a pairs figure skater at the 2006 Olympiad in Torino, Italy. But this high-stakes gamble was just the first of many for this athlete-turned-entrepreneur.

Why did the young Olympic hopeful stake so much on coming to Montreal? At the time, the choice was somewhat pragmatic – in those days, the skating world centred around Montreal and Toronto, so it was natural for someone seeking to be the best to surround himself with the best. But perhaps there was something more profound in his decision. Perhaps we can even detect the hand of destiny at work in the path of this Olympian.

Some hyperbole – supported by history – may illuminate this point. To wit: Montreal is the greatest sporting city in Canada, period. A strong claim, but let the evidence speak for itself.

A sporting city

Of course, one can point to Montreal hosting the Summer Olympic games in 1976. But there are 23 other cities around the world that have also had this distinction. But which other Olympic city can count on an institution like the Montreal Canadiens with their 24 Stanley Cup victories, a total unmatched by any other team in the league (and for a time, unmatched by any team in any sport on earth)?

And don’t forget the Montreal Royals, who provided the backdrop for the great Jackie Robinson to break the colour barrier in 1946. And the Montreal Expos, although they have since moved away, were another boundary-pushing outfit, as the first Canadian team to play in the majors.

The list goes on: Formula One, Tennis, Soccer, Boxing. You name it, this city has done it and at the highest level – even NASCAR racing.

But if we look even further back, we can see that Montreal – indeed, McGill University itself – was not just playing sports but creating them: Football in 1874, Hockey in 1875, and Basketball in 1891.

Not a lot of other cities have sat that close to the cutting edge, then or now.

Which brings us back to Buntin, and the hand of destiny. Because following his first Olympic dream, he took a run at a second one, with his eyes on a medal at the Vancouver Games of 2010. But life did not go exactly according to plan.

In 2007, his skating partner of the previous five years, Valerie Marcoux, decided to retire. Finding someone to replace her was no small task. Indeed, the search took months, and he drove thousands of kilometers to visit rinks across Canada and the US, until he found Meagan Duhamel.

Career-changing injury

But in the lead up to the 2010 games in what should have been a routine performance Buntin heard a wrenching ‘pop’ in his shoulder as he hoisted his partner in the air. He had torn three ligaments in his rotator cuff, and although the pair continued their campaign, training and competing as furiously as ever, they did not reach the selection standards and were left off the Olympic team.

This, however, was not the end of a career, but rather the beginning of a new one, a career and a company that once again brings Montreal to the cutting edge of sport – and artificial intelligence.

Realizing there was a whole world beyond the bubble of athletics, Buntin knew that education was the key. He had been dabbling in a new kind of coffee roasting as a hobby throughout his skating days and tried to turn that into a business. He quickly realized there was a lot more to running a business than meets the eye.

So with the all-in, high-stakes approach he was familiar with, and despite not having set foot in a classroom for over twelve years, in 2011 he sat for the GMAT exam and submitted an application to the MBA program at the Desautels Faculty of Management. He was accepted – if fact he was the first student in McGill history to be accepted for a graduate program without an undergraduate degree.

It was here that Buntin’s drive, experience and penchant for risk coalesced with what had perhaps been missing earlier in his career: vision. A vision not merely of achieving goals or obtaining success, but rather of what the world has yet to realize. It’s the stuff that, when properly executed, makes dreams into reality.

An opportunity in AI

The initial seed was to develop driverless cars. A laudable goal, but one fraught with engineering and computing challenges that have proved insurmountable for many. Even start-up giant Uber gave up on their efforts to bring this technology to the masses.

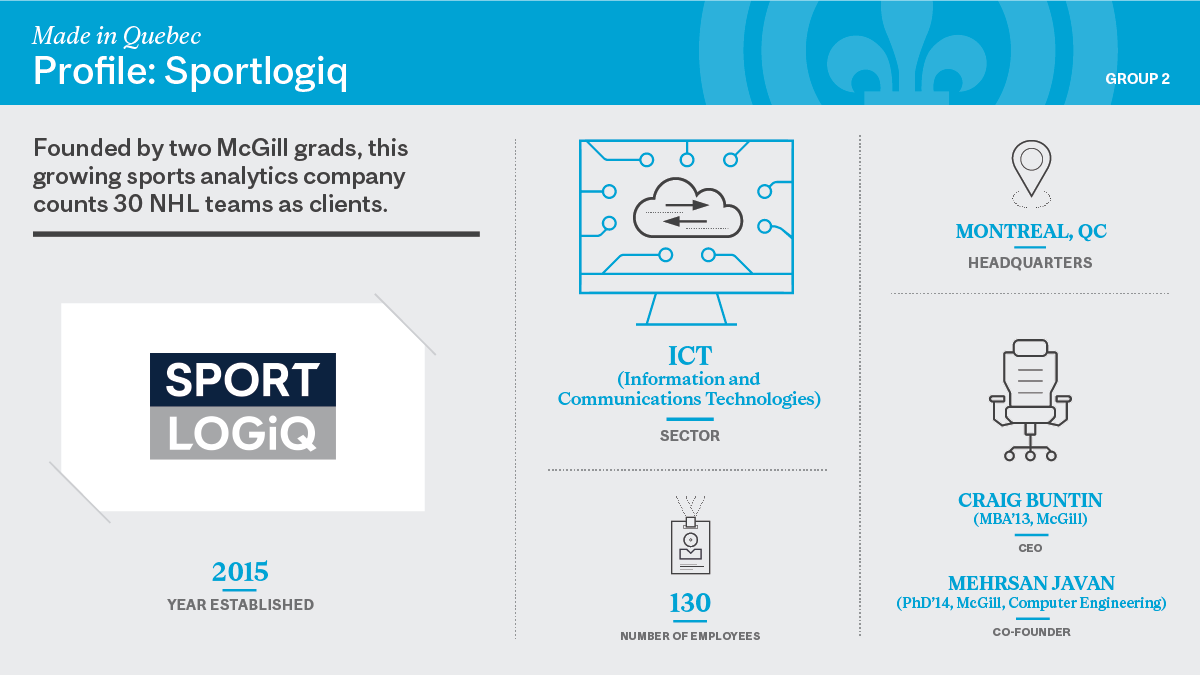

But in his work with Professor Martin Levine, along with project partner and eventual co-founder Mehrsan Javan, Buntin realized that using computer vision to detect traffic was highly applicable to an environment where human participants all wore numbers, moved in excellent lighting conditions and in environments with clear markings, i.e. professional sports.

“It’s a perfect petri dish with really pronounced and articulated problems,” explained Buntin on why they zeroed in on sports. “But these were technical problems that were more solvable than the variables involved with driving.”

Identifying a set of problems does not alone a business make, however. Buntin also gives recognition to the approach that McGill took to support the fledgling operation. They signed a license option agreement which temporarily gave them exclusive rights to the technology they needed. The agreement provides the option to make the license permanent or to let it expire, an ideal arrangement for a company still exploring its path forward (eventually they decided to convert the option into a full-fledged license).

“It was the perfect framework for what was still just an idea,” Buntin said. “In the early stages of business, people need to value risk a bit more. It was a real help that McGill understood this.” Eventually, Buntin and his team saw they had a real opportunity on their hands and agreed to purchase the license.

From start-up to scale-up

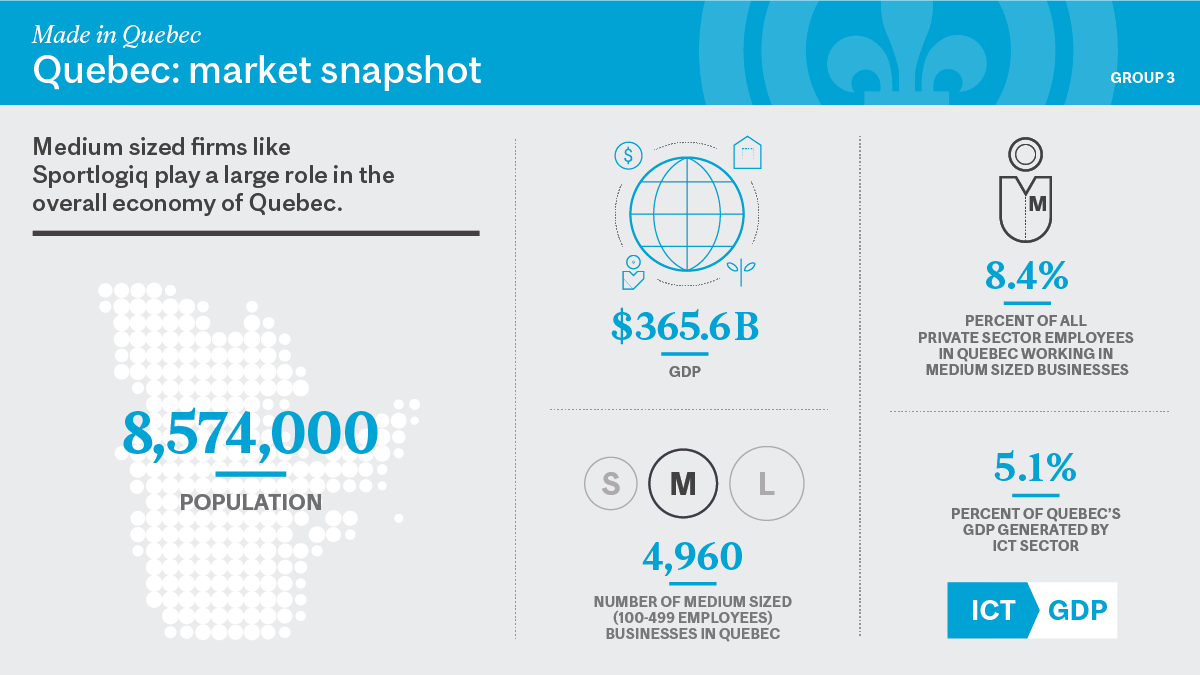

And with that, Sportlogiq was born. Founded in 2015, the company went through TandemLaunch, a Montreal-based start-up incubator – which was soon followed with a major investment by entrepreneur extraordinaire Mark Cuban. Things have since moved quickly for the dynamic start-up, which now boasts over 130 employees and two satellite offices in BC and Ontario in addition to its Montreal headquarters. In 2020, the company made the Globe and Mail’s list of Canada’ fastest growing companies, coming in at number 52 for revenue growth of over 1000% over a three-year period.

So what does the company offer to warrant this rapid growth? Simply put, they provide sports teams with a means to control their own destiny. How? Sportlogiq uses AI-based machine learning to analyze sports performance, based on the existing video feeds provided by broadcast television. Already the company has signed agreements with 30 of the 31 teams in the NHL and is growing into other sports like NFL football.

Many readers of course will be familiar with Moneyball, the 2011 film and book that described the success of major league baseball team the Oakland Athletics at using a data-driven approach to nearly win the American League championship in 2002. Naturally, in the competitive world of pro sports, this approach has become the standard, but Sportlogiq’s offering takes this to a whole new level.

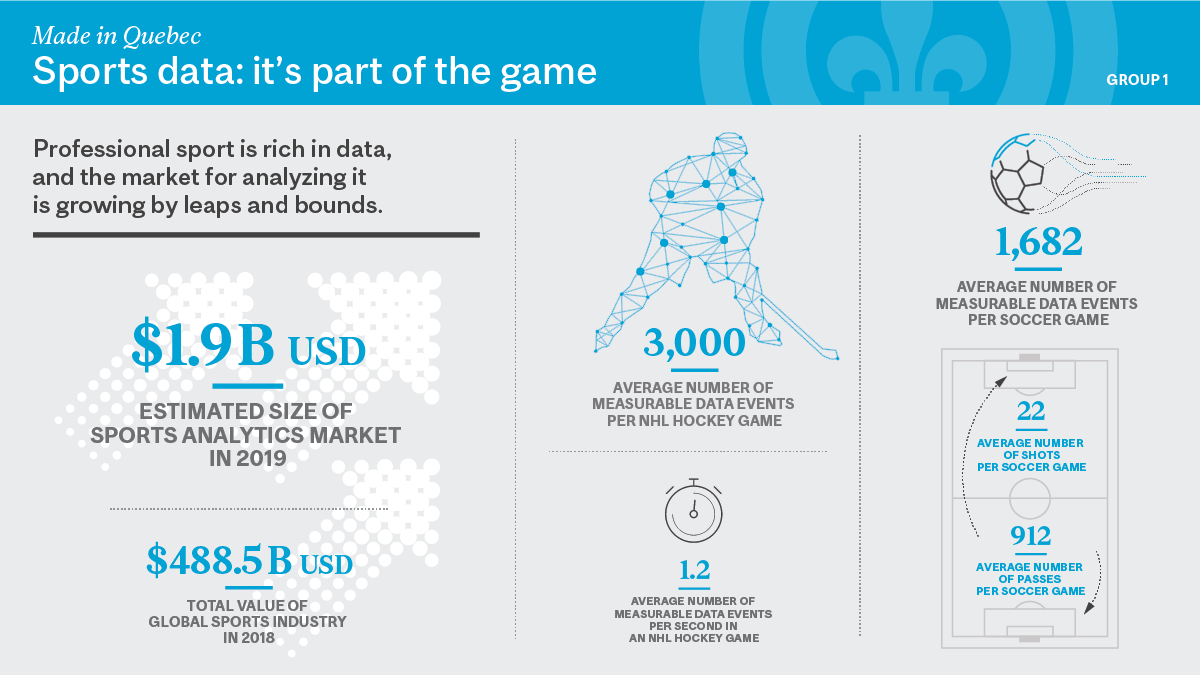

For example, Sportlogiq’s technology is so sensitive it can record a measurable action every 1.2 seconds during a typical professional hockey game. Over the course of a 60-minute game, that translates into 3,000 potential data points. And no data point is too small to be ignored: Angle change of play preceding shot attempt, offense generating plays, loose puck recoveries, expected goals per shift. These are just a small set of the variables they can analyze.

All of these measurements mean real value for teams, whether it’s pre-game preparation, post-game analysis or scouting for the next Wayne Gretzky. And the benefits for spectators are also huge. That ineffable ‘momentum shift’ where the course of a game seems to change can now be identified and quantified – the insight of the play-by-play caller is no longer a monopoly.

And the brilliant part? None of this requires any special investment on the part of the client. No hardware or software to install, and no changes to your stadium or infrastructure.

Sportlogiq first targeted hockey teams as potential clients – a natural choice as a Canadian company – and they have been able to sign up 30 out of the NHL’s 31 teams as clients. Reaching out to hockey in other countries – Sweden, for example – was a logical next step.

All of this has the makings of a dream job for a hockey nerd, something confirmed by Nick Czuzoj-Shulman, a senior data analyst with the company. Coming from a background as a data analyst for clinical research trials, he is a self-confessed hockey obsessive. Born and raised in Montreal, it is a no-brainer that is also a Canadiens fan. So what’s it like working at Sportlogiq? “It’s a dream come true,” he said. Part of this stems from the company culture, he adds. “We don’t take ourselves seriously, but we take our work seriously.”

Beyond hockey

But while parsing NHL hockey may be a dream for some, the reality is that the league is small fry in the sports world. The big dog, NFL football, is valued at over $90 billion USD, or almost four and a half times the NHL, even though football players only play 20% as often as their skating colleagues. So far, the company has concluded deals with four teams.

But tackling the NFL (pun intended) is no small task. While they were able to leverage their strength in hockey, it still required substantial investment to make the necessary transformations for the new sporting model. And these were investments without any real guarantee that they would lead to direct business.

Because, as mentioned earlier, Moneyball has been a ‘thing’ for over a decade now, and Sportlogiq is far from alone in this field. In fact, the industry of sports data is booming, already generating $2 billion USD in business activity as of 2019. It’s predicted to reach $5.2 billion by 2024, according to some analysts.

Growth, however, was hard to come by this past year, as a predictable result of the Covid-19 pandemic. While the company was able to avoid a massive downturn in its operations, it did mean a few adjustments were necessary.

“When the pandemic hit, we were forced to grow up very quickly.” explained Buntin. “We needed to prepare for a long and difficult fight where resources would be scarce. Culturally, that's a far cry from the early startup mentality of 'let's tear down the walls and flip the sport industry on its head.' We went back to the drawing board on almost every one of our products, focusing only on those that we knew we could do better than anybody else in the world.” The company not only managed that shift in culture, but unlike so many other sport companies, it grew its revenue through the pandemic.

But despite this challenge the company maintains a low-key and relaxed atmosphere, at least according to marketing content manager Brandon Di Perno. Hired in 2019, he came to Sportlogiq after a previous stint in a Madison Avenue advertising firm, so one can assume he knows energy when he sees it.

“The atmosphere at Sportlogiq is electric,” he said, speaking of the pre-Covid days. “People are really excited and passionate about what they are doing.”

Di Perno was quick to list the company’s values. All too often, statements like these result in much eye rolling, but in their case, it is hard not to be persuaded that it makes a difference to their employees. For example, Nice people finish first is one of their tenets. And so is the Olympic credo of citius, altius, fortius (i.e. faster, higher, stronger), a clear tip of the hat to Buntin’s background.

Quebec support for small business

But in addition to their somewhat quirky set of values Buntin also points to another important factor for their success: Quebec. It’s well known that the province does a lot to nurture its homegrown athletic talent. This is reflected in Quebec’s enviable Olympic record, for example. At the PyeongChang Winter Games in 2018, Quebec alone would have ranked tenth overall for the number of gold medals (four).

“Some of Canada’s best athletes are here in Quebec,” Buntin explains. “But they don’t have big egos. There is a willingness to roll up the sleeves and get work done. I don’t think you find that everywhere.”

It’s also a province where support for startups is prominent. For example, Quebec offers more generous tax credits for R&D expenses than other provinces – up to 50% more – and for several years it ran a program to help companies secure their first patent (the Premier Brevet program). Although this was eventually discontinued, Quebec companies have more Intellectual Property than other companies in Canada, according to StatCan. Sportlogiq is firmly in this camp, with nine registered patents and new research underway.

Certainly, financial support from both the Quebec and federal government (through the NRC-IRAP program, and the agencies NSERC and Mitacs) were also important factors, as it gave them the flexibility to reach out to new markets like NFL. But while the bottom line is arguably every company’s raison d’être, it takes more than just money to make things work.

Part of the pains that face any startup is ensuring there is a clear understanding of what the company is really about. On this point, Buntin is clear: despite the inherent focus implied by the name, Sportlogiq is a technology company.

“AI is a foundational technology that will reshape industries,” he said. “We are a technology company that began with a focus on services to the professional sports industry.”

As to what this means more specifically for Sportlogiq’s future, Buntin was reticent. After hockey, football and possibly soccer, what other sports are they targeting? Or will they pivot to a new industry? The ex-Olympian is playing his cards close to his chest, but if past accomplishments are anything to go by, you can be sure of one thing: it’s destined to be big.