Enlarge

Donor: Children’s Memorial Hospital of Montreal (CMH)

Date: 1946

Size (H x W x D cm): 13 x 10 x 3

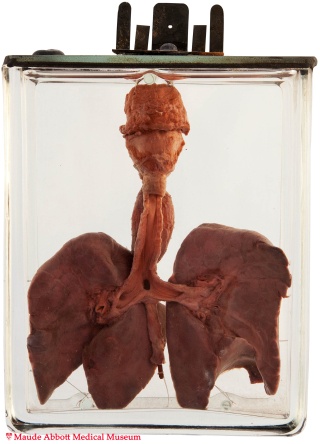

The trachea has been opened anteriorly to show the origin of a fistula with the distal esophagus just above the carina (A, arrow). A red rod exits from the esophagus inferiorly. A back view (B) shows the dilated upper esophageal “pouch” located above the atretic portion of the esophagus.

A. Click on image to enlarge B. Click on image to enlarge

History: Six day-old infant boy. Unknown history or additional abnormalities.

Comment: The respiratory system begins as an outgrowth of the ventral foregut. Initially, the two are widely connected; however, the connection is soon closed by an esophago-tracheal septum (except at the entrance to the presumptive larynx). Deviation of this septum posteriorly is thought to lead to focal esophageal atresia and/or communication with the adjacent trachea.

Several anatomic types of the anomaly are described, most of which have an associated tracheo-esophageal fistula. A blind ending proximal esophagus with fistula between the lower esophagus and the trachea is the most common, comprising about 85% of cases. It is usually manifested in infancy as feeding difficulty following regurgitation of milk from the proximal esophageal “pouch”.

The anomaly occurs in about 1 in 2000 to 4000 live births. Although often “sporadic”, it is not uncommonly associated with trisomy 13, 18 or 21. Maternal hydramnios is frequent because of inability of the fetus to swallow amniotic fluid. In the past, “failure to thrive” or infection from accompanying aspiration pneumonia led to death of most affected individuals in infancy (as in the three examples shown here). Early recognition and surgical repair of the abnormality can now lead to cure in most patients. However, associated congenital anomalies (particularly cardiac) are not uncommon and may affect overall prognosis.