By 2500 earth could be alien to humans

To fully grasp and plan for climate impacts under any scenario, researchers and policymakers must look well beyond the 2100 benchmark. Unless CO2 emissions drop significantly, global warming by 2500 will make the Amazon barren, the American Midwest tropical, and India too hot to live in, according to a team of international scientists.

“We need to envision the Earth our children and grandchildren may face, and what we can do now to make it just and liveable for them,” says Christopher Lyon, formerly of University of Leeds and now a Postdoctoral Researcher at McGill University. “If we fail to meet the Paris Agreement goals, and emissions keep rising, many places in the world will dramatically change.”

The scientists from Montreal and the United Kingdom ran global climate model projections based on time dependent projections of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations for low, medium, and high mitigation scenarios up to the year 2500. Their findings, published in Global Change Biology, reveal an Earth that is alien to humans.

Vegetation moves to the poles

Under low and medium mitigation scenarios – which do not meet the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius – vegetation and the best crop-growing areas may move towards the poles. The area suitable for some crops would also be reduced. Places with long histories of cultural and ecosystem richness, like the Amazon Basin, may become barren.

The Amazon: The top image shows a traditional pre-contact Indigenous village (1500 CE) with access to the river and crops planted in the rainforest. The middle image is a present-day landscape. The bottom image considers the year 2500 and shows a barren landscape and low water level resulting from vegetation decline, with sparse or degraded infrastructure and minimal human activity. Credit: James McKay, CC BY-ND, The Conversation

Tropical regions uninhabitable

They also found that heat stress may reach fatal levels for humans in tropical regions that are highly populated. Even under high-mitigation scenarios, the team found that the sea level keeps rising due to expanding and mixing water in warming oceans.

“These projections point to the potential magnitude of climate upheaval on longer time scales and fall within the range of assessments made by others,” says Lyon.

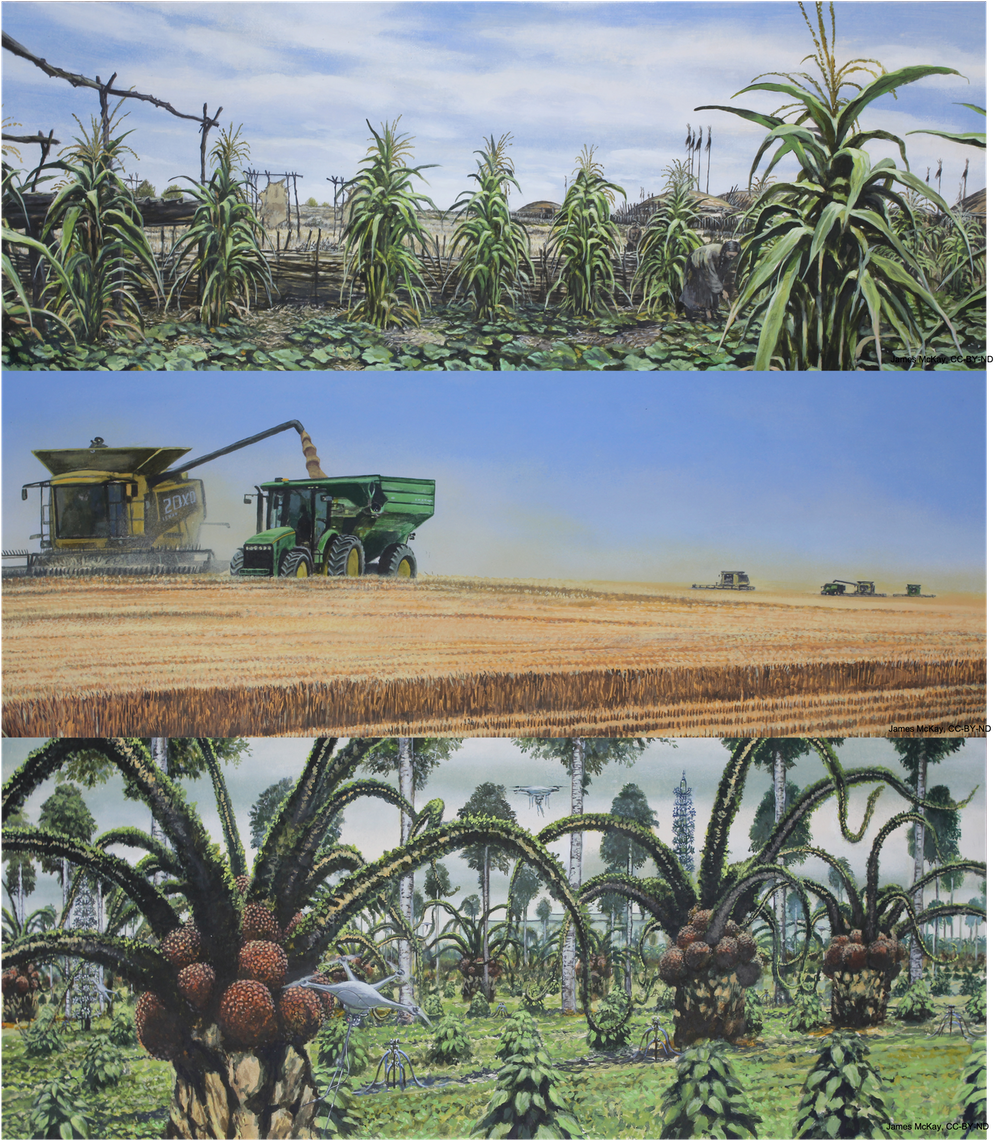

Midwest US: The top painting is based on pre-colonisation Indigenous cities and communities with buildings and a diverse maize-based agriculture. The second is the same area today, with a grain monoculture and large harvesters. The last image, however, shows agricultural adaptation to a hot and humid subtropical climate, with imagined subtropical agroforestry based on oil palms and arid zone succulents. The crops are tended by AI drones, with a reduced human presence. Credit: James McKay, CC BY-ND, The Conversation

Looking beyond 2100

Although many reports based on scientific research talk about the long-term impacts of climate change – such as rising levels of greenhouse gases, temperatures, and sea levels – most of them don’t look beyond the 2100 horizon. To fully grasp and plan for climate impacts under any scenario, researchers and policymakers must look well beyond the 2100 benchmark, says the team.

“The Paris Agreement, the United Nations, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s scientific assessment reports, all show us what we need to do before 2100 to meet our goals, and what could happen if we don’t,” says Lyon. “But this benchmark, which has been used for over 30 years, is short-sighted because people born now will only be in their 70s by 2100.”

Climate projections and the policies that depend on them, shouldn’t stop at 2100 because they cannot fully grasp the potential long-term scope of climate impacts, the scientists conclude.

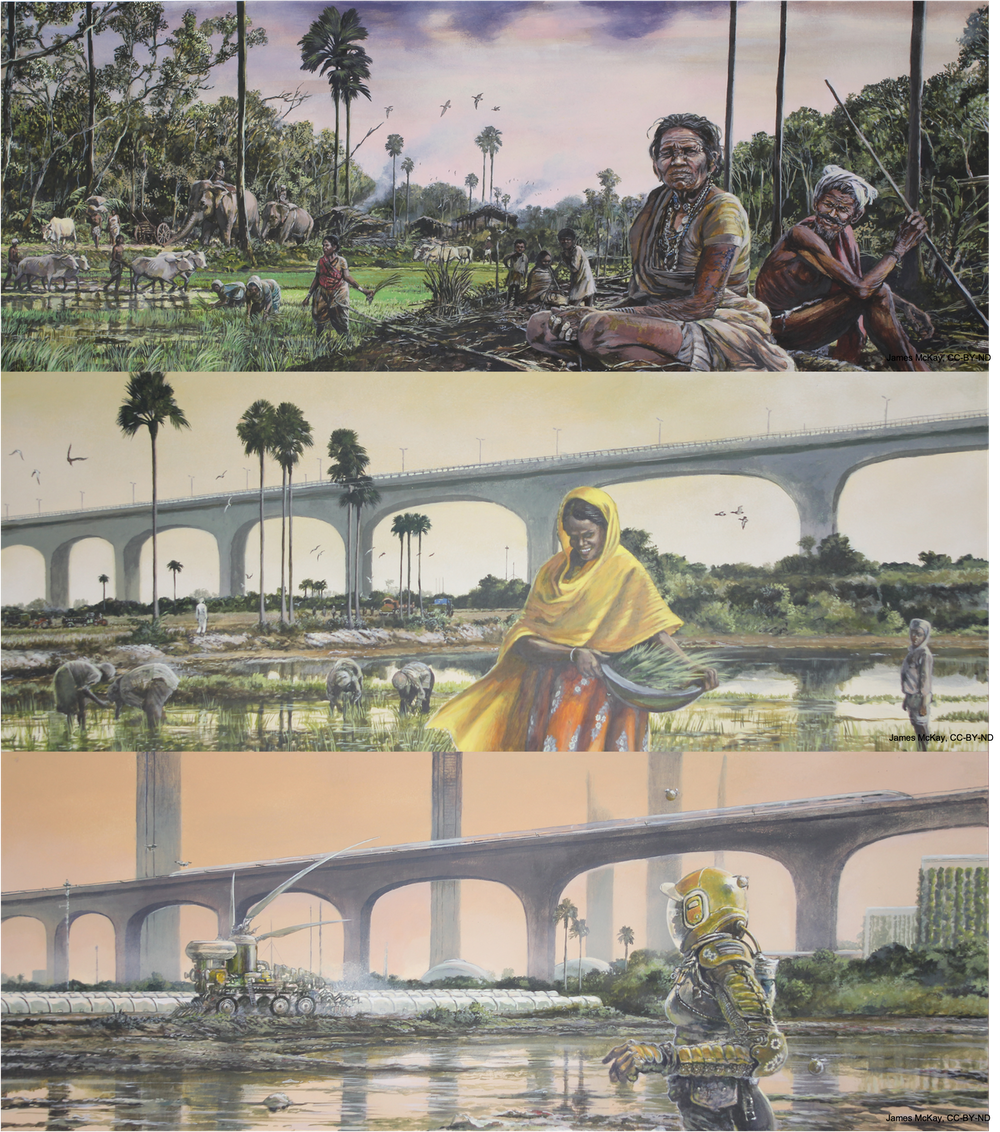

The Indian subcontinent: The top image is a busy agrarian village scene of rice planting, livestock use, and social life. The second is a present-day scene showing the mix of traditional rice farming and modern infrastructure present in many areas of the Global South. The bottom image shows a future of heat-adaptive technologies including robotic agriculture and green buildings with minimal human presence due to the need for personal protective equipment. Credit: James McKay, CC BY-ND, The Conversation

|

About this study "Climate change research and action must look beyond 2100" by Christopher Lyon, Erin E. Saupe, Christopher J. Smith, Daniel J. Hill, Andrew P. Beckerman, Lindsay C. Stringer, Robert Marchant, James McKay, Ariane Burke, Paul O’Higgins, Alexander M. Dunhill, Bethany J. Allen, Julien Riel-Salvatore, and Tracy Aze was published in Global Change Biology. The research was supported by the White Rose University Consortium. |

About McGill University

Founded in 1821, McGill University is home to exceptional students, faculty, and staff from across Canada and around the world. It is consistently ranked as one of the top universities, both nationally and internationally. It is a world-renowned institution of higher learning with research activities spanning three campuses, 11 faculties, 13 professional schools, 300 programs of study and over 40,000 students, including more than 10,200 graduate students.

McGill’s commitment to sustainability reaches back several decades and spans scales from local to global. The sustainability declarations that we have signed affirm our role in helping to shape a future where people and the planet can flourish.