Pushing the speed limit: What will the future of the Internet look like?

More people rely on the Internet to work, play, shop, and connect with others, growing the demand for global data traffic by 40% every year. To keep pace with the drive for more bandwidth, McGill Professor and Canada Research Chair David V. Plant and his team are working on pushing the speed limits of the Internet by making data transmission quicker, more efficient, and greener. Recently, they set a world record by achieving a 1.6 Terabits per second data transmission over a distance of 10 kilometers – about a thousand times faster than common household Internet speeds.

McGill Professor and Canada Research Chair David V. Plant and his team.

“Every time you use apps like Uber or Amazon, you’re touching the Internet. All these interactions flow through optical fibre transmission systems that use light signals to send data to and from your mobile phone, tablet, or computer,” explains Professor Plant.

“These transmission systems which constitute the plumbing of the Internet span the globe. As of 2020, over 5 billion kilometers of fiber-optic cable has been deployed around the world, this is enough optical fibre to go to mars and back almost nine times,” he adds.

Optical fibre lines consist of hundreds of small strands of glass cables, each about the diameter of a human hair. Data is transmitted using pulses of light that travel across fibre cables at close to the speed of light.

Fiber optic patch panel showing many optical connections to/from the Internet.

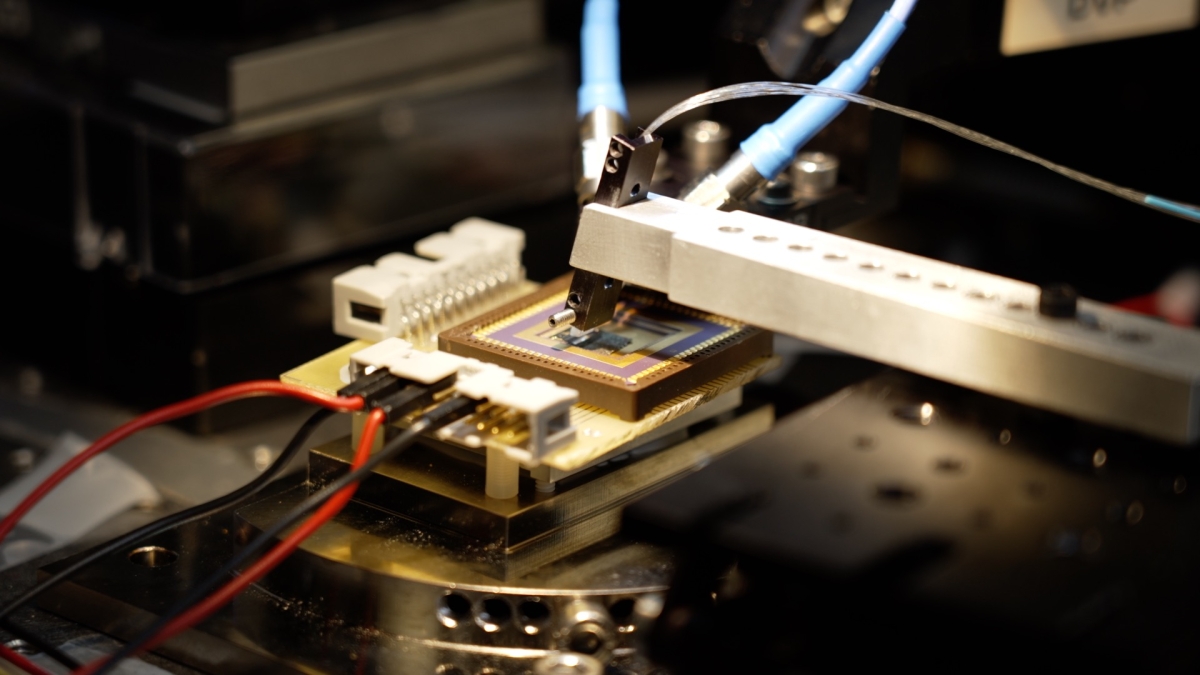

Specializing in next generation optical fiber transmission systems, Professor Plant’s lab is one of the few worldwide – and the only one in North America – equipped with advanced capabilities to push these systems to the limit. Working with industry partners, the team developed new technology using low-cost components to achieve the record-breaking data transmission.

“We’ve achieved much faster data transfer over longer distances compared to traditional methods, while reducing power consumption, cost, and space needs,” says Professor Plant. According to the researchers, this is good for companies like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, that run data centers interconnected by such fiber optic networks over distances of tens of kilometers.

So, what will the future of the Internet look like? “What comes will be even more transformative for any and all Internet users,” he says.

An electro-optic modulator operating with an optical and radio frequency probe station.