We are living in the future. We have robotic personal assistants, watches that replace credit cards, phones that recognize our faces, and self driving cars are just around the corner. But for all our advancement, patients with diabetes still need to stab themselves multiple times a day to check their blood glucose levels. There has to be a better way, right?

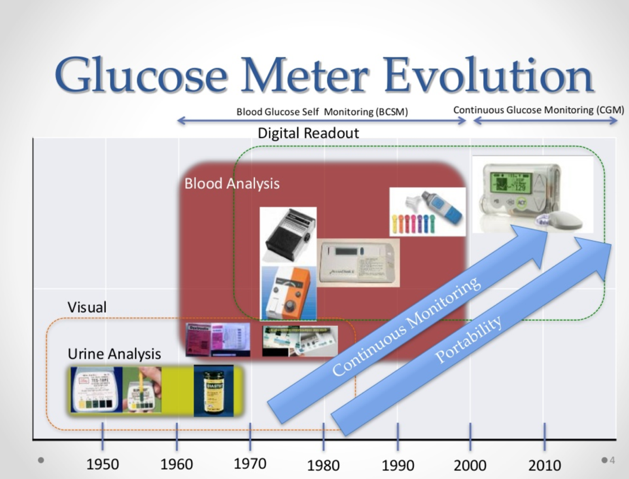

The history of glucose meters starts in 1956 with Leland Clark presenting a paper on an oxygen electrode, later to be renamed after him. Six years later the Clark electrode had been developed, with the help of Ann Lyons, into the first glucose enzyme electrode. These early glucose meters were large, bulky and only used in hospitals. It wasn’t until 1981 that at-home monitors were popularized, sold on the market by the same names you’d recognize today: Glucometer and Accu-chek.

These glucose meters worked by a method still used today that’s quite similar to how breathalyzers detect blood alcohol content. Electrons are transferred from the glucose in blood through molecules until it reaches the electrodes in the glucometer. These moving electrons create an electrical current proportional to the amount of glucose in the blood, and the number appears on the monitor.

But what if we could measure our blood sugar without having to prick our fingers?

A lot of research and development has gone into that very idea.

Instead of measuring the glucose in blood directly, attempts have been made to measure the glucose in other fluids. Urine tests have been available for much longer than even blood tests but visiting a bathroom every time you need to test your sugar is far from ideal as those with type 1 diabetes may need to test their sugar up to 12 times a day!

New technologies are looking at using tears. Since these fluids are naturally external to the body their measurement needs no needles, something that would decrease the cost of testing and likely increase the reliable tracking of patients’ blood sugar.

Google notably prototyped a contact lens in 2014 that would contain the chips and sensors to measure sugar levels and either change colour accordingly, or transmit that data to an external device. Because of the low volume of tears, the lenses need to be exceptionally accurate. Reliable relationships between the glucose in tears and in blood need to be established and contact lens solution that doesn’t inhibit the lenses needs to be developed.

A few other technologies have been investigated for non-invasive blood sugar testing. A device using near-infrared spectroscopy that would shine light through the earlobe to sense glucose was prototyped, but required a lot of measurements (like earlobe width and blood oxygen levels) to calibrate (though a similar product has been sold outside of the US and Canada). Scientists have attempted to create devices that would pull glucose out from the blood through the skin, using chemicals or electrical currents, as well as devices that would measure blood sugar via polarized light measurements, but at least as of yet, none of these devices have been commercially available in Canada.

One product that may soon be seen on market is Glucair, which functions similarly to a breathalyzer. It analyzes the acetone present in your breath to take a measurement of your blood glucose level. This system could be made quite small, like modern breathalyzers, and would require no finger pricking or needles of any kind.

For now the best alternative to finger prick tests are continuous glucose sensors. They consist of a needle that is embedded in the skin that can take blood samples very often, and the circuitry to measure the glucose content. The results are seen by scanning the sensor with a receiver, a smartphone, or via bluetooth connection. They give live results and can last up to 7 days, but tend to be very expensive, given the disposable nature of the inserts, and aren’t always covered by insurance like glucometers are.

In Canada there are a few neat options available. The Freestyle Libre is what's called a flash glucose monitoring system. The small sensor is inserted into the skin and worn for 14 days, and can be scanned whenever needed by the receiving decide to get blood sugar levels. The Dexcom G5 is also a small sensor that can be worn for 10-15 days, but it transmits wirelessly to your smart devices. This makes it especially useful for parents or caretakers wanting to monitor someone else's glucose levels.

(Click here to view a higher resolution version of this image)

Continual monitoring allows greater accuracy in insulin doses and allows a patient to provide more information about their blood sugars to their doctors. Ideally continual sensors will also be able to communicate directly with insulin pumps, so that type 1 diabetics can receive their correct dose without needing to finger prick first.

Considering how far we’ve come since the advent of blood glucose monitoring in the 1960s, I have faith continuous and non invasive technologies are coming. It’s really just a question of how many needles diabetics will have to endure before they do.

Want to engage with this content? Comment on this article on our Facebook page!