In a recent test, a little over a thousand American adults were shown eight videos, and they had to choose if the video was real or if it had been completely generated by an artificial intelligence (AI). Half of the videos were real; the other half, AI generated. The results show that, on average, people couldn’t tell. As a group, they were split fifty-fifty on almost all of them.

Technology has improved dramatically in the last couple of years to allow for the wholesale creation of images, texts, audio, and video that appear to come from humans but are actually made by computers. Meanwhile, our species is already at a profound disadvantage when it comes to media literacy: most teenagers can’t tell the difference between a fact and an opinion in a text they read, and nearly half of all Canadians are functionally illiterate. We have the makings of a massive problem on our hands.

Even if the fakes are not that good, their mere existence facilitates the manufacture of doubt. A snippet of audio or a smartphone snapshot makes you look bad? It’s clearly a fake! (Just ask Donald Trump, who is already using this defence.)

Trying to explain how these AIs work is only partially possible, as even experts don’t understand exactly what happens inside of these black boxes. Suffice to say that AI platforms like ChatGPT and DALL-E can do things that would normally require a human brain to do, which includes forms of learning. To learn, these AIs can be trained by humans in different ways. They can be fed large data sets and, much like with a dog, their learning can be reinforced using rewards and penalties to train them to achieve a desired result. Free-to-use and pay-to-play services are now available, where anyone can converse with an AI or ask that AI to generate multimedia content based on a written request. And these AI systems are getting very good at meeting our quality standards very quickly.

In the coming years, we will all need to play detective when evaluating questionable content online. There are signs that point the finger (or too many fingers, as we will soon see) at AI, signs we should learn to recognize, even if all of this advice will be outdated six months from now as technology catches up.

Butter fingers

Artificial intelligence can create images from scratch from a text prompt that anyone can write through an interface like Microsoft Bing, for example. While the realism of these images has improved immensely in a short amount of time, there are still telltale signs we can spot in many of these AI creations. I generated a few as examples.

Human hands are already difficult to draw in three-dimensional space, and AI still generates hands with too many fingers and with fingers that blend into one another in weird ways. AI can generate realistic hands, but it’s still not a sure thing.

The hands in this one look very realistic (even down to the barely visible hair on the hand), but the watches in the box are only approximations of watches.

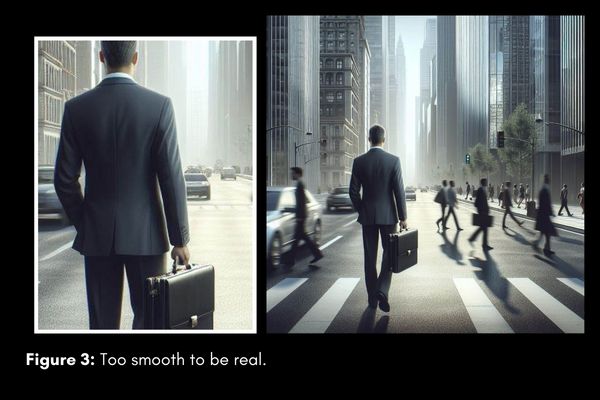

Meanwhile, the people the AI generates tend to be conventionally attractive and youthful: lean, with large eyes, and a lot of hair. Moreover, in this particular example, the model’s skin and hair are just a bit too smooth to be realistic, a common problem with AI-generated images as we can also see below.

There is an uncanny sheen to the man’s suitcase, suit, and hair. Even the buildings lack details when you lean in to take a closer look.

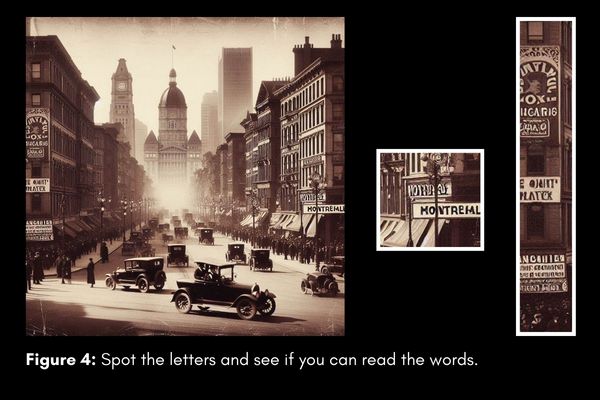

AI currently struggles with words. I asked it to generate a photograph of Montreal from 1931. First off, the tall skyscraper right of centre is clearly out of place, and while the overall architecture certainly suggests Old Montreal, anyone who has been to our city will know that this is not Montreal. But notice the signs: some of the letters are real, while others are gibberish. Someone wanting to spread disinformation could replace these signs with proper letters in an image editing software, but images fresh from the AI will very often show mumbo-jumbo instead of actual words.

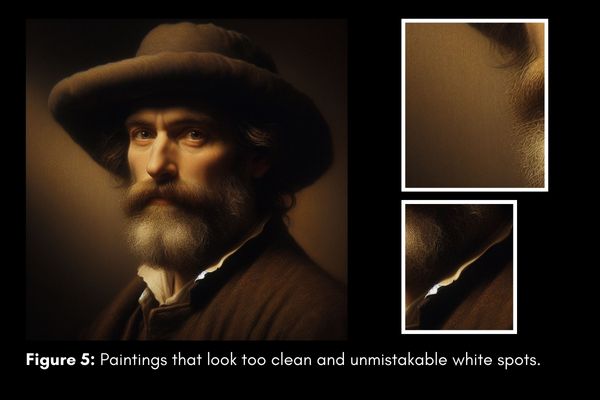

When asked to generate fake paintings, AI is pretty good. The above shows DALL-E aping Rembrandt. But the painting is too clean. Look at that background. It should show the wear and tear of time. Also, notice the man’s collar. Those white tips are very common in AI art. Scroll back up to figure 2 and you will notice that the hand holding up the arm that’s wearing the watch also has unnatural white spots where the skin should be.

And the next time you feel like ordering a meal through a food delivery app, keep in mind that some kitchens listed on these apps have been caught using AI-generated images of their offerings. Notice the unnatural colours and the lack of details.

A glossy sheen, too many fingers, and incomprehensible words are clear signs that the image was AI generated, and the more you play with these AI services, the better you will be able to recognize the level of realism that AI is actually capable of right now. It’s like training your eye to recognize Romantic paintings or the works of Jackson Pollock. At some point, your brain subconsciously picks up on revealing patterns that help identify what kind of painting you are looking at.

There are online detection tools that exist, where an image can be submitted to know if it has been generated by AI or not. In fact, these image detectors themselves use AI in order to spot other AIs, but are they any good? A summer fellow for Bellingcat, the investigative journalism group, tested one image detector’s accuracy, and while it was very good when given high-quality images, it started to make mistakes when the images submitted were compressed and of suboptimal quality. This is a problem because low-quality images can easily circulate on social media, and those are the sorts of pictures that people will want to authenticate.

Before we move on to AI-generated text, it’s worth pointing out that fake images are not new: image editing software has been available for decades and it is all-too-easy to doctor an image, as we were reminded recently during that whole Kate Middleton image debacle.

An arms race

When my friend Aaron Rabinowitz, a Ph.D. candidate in education and lecturer in philosophy at Rutgers University, decided to prompt ChatGPT to write an article about artificial intelligence for The Skeptic magazine, he noticed something peculiar. In a paragraph entirely written by the AI and focusing on the claim that it just engages in mimicry, the AI wrote, “First, let’s address the parrot in the room.”

ChatGPT had made a joke.

It was familiar with the expression “the elephant in the room.” It was also familiar with the phrase “stochastic parrot” used to indicate that large language models like ChatGPT do not understand what they are writing, much like a parrot simply repeats words it has heard. And it “understood” that a parrot and an elephant were two animals, and that the one could replace the other in this context to make a coherent quip.

People still playing around with ChatGPT version 3.5, which is free, may not realize how much more impressive the paid version, version 4, is and how difficult it is now to detect if a text was generated by a human or by artificial intelligence. Unlike with images, there is no smoking gun. And the people most preoccupied with telling the difference right now seem to be educators, who often turn to online tools to know if an essay their student submitted was actually penned by ChatGPT.

These detection tools have been tested by researchers and the results should worry anyone looking to use them to launch accusations. At least two studies were published last year feeding the abstract (or summary) from many academic articles published before AI technology was available into AI detection tools. All of these abstracts had been written by humans, and yet the detection tools flagged some of them as having been written by AI. The largest of the two studies tested thousands of abstracts published between 1980 and 2023: up to 8% of them were mistakenly attributed to a computer. These abstracts represent the sort of formal writing that university students will be asked to produce in class. Why are 8% getting erroneously flagged? In my opinion, academic writing has become so stiff and, let’s be honest, boring, it can easily look like it was formulated by a computer.

To add a layer of complexity, students attending a school in a language they are not fluent in may be tempted to write an assignment in their native tongue and use Google Translate or a similar online service to translate it into the school’s language. That simple act can get their text flagged as “AI-generated” by these detection tools.

Meanwhile, students who do use AI to generate their homework can more easily evade detection by changing some of the words with synonyms (a process known as “patchwriting”) or adding extra spaces. The companies behind these AI detection tools will claim they are highly accurate, with minimal false positives and false negatives, and that papers published in 2023 showing otherwise are now outdated. But the AIs these papers were using have also become more sophisticated. It is a rapid arms race and not one that the detection tools are likely to ever win.

This leaves teachers and professors having to decide if they want to play cyber-cop by feeding their students’ assignments into unreliable tools and confronting the flagged students with what is essentially a black box. These tools do not provide evidence for their results. They use rules like a text’s randomness (humans tend to write in chaotic ways; AIs, not so much) and variation in the length of sentences (we vary; machines do not), but unlike detecting a copy-and-paste job from a different author, there is no sure sign here. And how can a student defend themselves against these accusations when no real evidence is presented?

At least machines can’t steal our voices yet. Right?

The future is here

The late comedian George Carlin had his voice cloned and rendered by an artificial intelligence for a controversial comedy special earlier this year. It later came out that the jokes were written by humans, but the voice was made by a computer trained on archival material. You may think the process of recreating a voice like Carlin’s is tedious. It really isn’t. I managed to clone the voice of our own director, Dr. Joe Schwarcz, in about five minutes by submitting a three-minute sample from his radio show to ElevenLabs’ VoiceLab, typing out a text for the voice to read out, and tweaking the settings. You can hear the final product by clicking here.

I have done something similar for both my voice and that of my podcast co-host, and I would say that the voices are 90% accurate. In those two cases, the AI got the “a” sound wrong, overly nasalizing my co-host’s. You can also hear in the fake Joe Schwarcz example that the word “total” isn’t quite right if you are very familiar with how he sounds. Keep in mind: this is the worst the technology will ever be. It will improve in the blink of an eye.

As if this wasn’t concerning enough, there is now AI-generated video. The makers of ChatGPT have created Sora, which can generate video from text. It is not yet available for the public to play with at the time of writing, but the examples the company has released are frighteningly good, including photoreal humans and dogs. They’re not perfect: tech reviewer Marques Brownlee spotted a horse suddenly vanishing in the middle of a clip that’s meant to represent California during the Gold Rush, and weird hands and a candle with two flames at a birthday party. But how many people are eagle-eyed when scrolling through social media? Already, creators are churning out AI-generated videos to keep children entertained on YouTube, and it’s all starting to feel a little dystopian.

The rise of AI-generated content asks us to wrestle with complex moral questions that have no easy answers. Should non-English-speaking scientists use AI to write their papers and help disseminate their results to an international audience? Should educators attempt to police their students’ use of AI using opaque and unreliable tools, or should they see artificial intelligence as equitably distributing the ability to cheat, which used to be reserved to wealthier students who could pay others to do their assignments? Should deceased celebrities be revived using AI to generate money for studios that don’t employ them?

How do we even begin to answer these questions?

Let me ask ChatGPT.

Take-home message:

- AI-generated images often display signs that they were made by a computer: colours and surfaces are too smooth and glossy, background objects are misshaped, lettering is gibberish, and hands are (often though not always) anatomically incorrect

- There is no foolproof way of detecting if a text has been generated by an AI or written by a human, as online detection tools do produce false positive and false negative results

- AI can clone human voices to a frighteningly accurate degree, though some of the sounds may be slightly off