Today, the conventional treatment of ulcers often involves the use of antibiotics. That’s because there is now clear-cut evidence that many ulcers are caused by the Helicobacter pylori bacterium. When the bacterial connection was first suggested by Drs. Barry Marshall and Robin Warren back in the 1980s, it was certainly in the “alternative” realm. After all, physicians “knew” that ulcers were caused by stress and excess stomach acid. Skeptics, appropriately, wanted evidence before they jumped on the bandwagon. And it didn’t take long for it to be provided.

In a cavalier, and somewhat foolhardy fashion, Marshall drank a solution of Helicobacter pylori and developed a case of gastritis. No ulcer formed, but the experiment managed to stir the scientific community into action and within a few years hundreds of papers were published on the subject. Controlled trials were carried out, and antibiotics were clearly shown to be an effective treatment for ulcers. Today, this is the preferred treatment and is taught in every conventional medical school. Although initially some physicians may have scoffed at the idea of ulcers being caused by bacteria, they were quickly won over by the evidence. Contrary to what is often claimed by alternative practitioners, scientists are not closed-minded about approaches that are not mainstream, they just would like to see some sort of evidence of efficacy before advocating them.

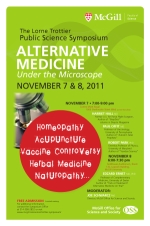

“Alternative” treatments span a wide spectrum of methodologies, ranging from the absurd, such as bathing in the light of the full moon, to acupuncture, possibly efficacious for some conditions. The intriguing question is why people flock to such treatments. After all, homeopaths, reflexologists, energy healers or magnet therapists cannot furnish proper scientific evidence for their claims. But they can offer patients charisma, time and hope. Often that is all that is needed. They are adept at using the placebo effect to great advantage and capitalize on the fact that many diseases are self-limiting and resolve by themselves. While in most cases alternative therapies are innocuous, there are exceptions. Patients may be lured away from effective treatments by seductive nonsense. “Alternatives” to vaccination or chemotherapy may indeed extract a high price.

Whatever one’s views on alternative medicine may be, there’s no question that the subject merits attention and discussion. There may be some gems among the rocks. Some science-based sifting is certainly in order—followed by putting the results under the microscope.