Have you ever heard the story of the Japanese dog, Hachikō? For years, Hachikō accompanied his owner, Ueno, on part of his commute to work, walking with him to and from the Shibuya train station. Even after Ueno passed away, Hachikō continued to walk to the train station, awaiting his owner’s return from the workday. Hachikō’s loyalty never wavered — he waited faithfully until the day he died, almost ten years later. There’s no better way to describe this story than one that tugs on your heartstrings, a distinct combination of fondness, sadness, and compassion.

The phrase is thought to be based on anatomical knowledge from the 15th century. Heartstrings were presumably the tissues and/or vessels that surrounded heart, holding them in place and guiding the emotions. These have since been defined as the pericardium and the great vessels, vital for cardiovascular function but not necessarily responsible for any emotional processing. The nickname “heartstrings,” however, remains common in anatomy education, referring to structures within in the heart called the chordae tendineae.

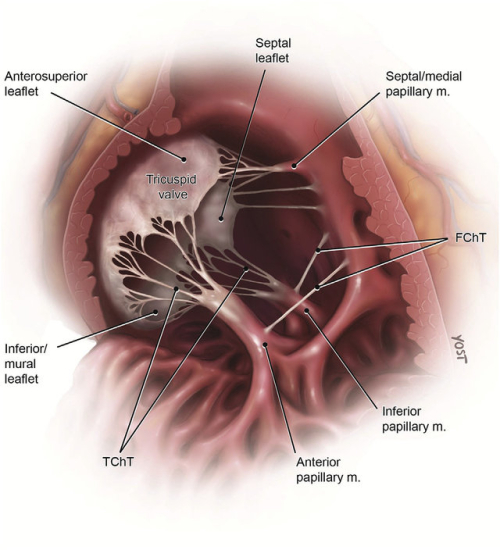

Chordae tendineae, which translates from Latin to “tendinous chords,” are exactly what the name suggests: tendinous connections found in two valves of the heart. The human heart is divided into four chambers, two atria on top and two ventricles below. Blood coming from the body cycles from atrium to ventricle on the right side of the heart before going to the lungs to become oxygenated. After leaving the lungs, the blood cycles through the left atrium and ventricle before being pumped to the rest of the body through the aorta. As blood flows from atrium to ventricle, it's regulated through valves called the atrioventricular valves (“tricuspid” on the right and “mitral” on the left), which is where the chordae tendineae are found.

Image Source: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tria.2019.100049

Each valve resembles a parachute, with the leaflets of the valve being the canopy and the chordae tendineae being the strings. The chordae tendineae are anchored through small muscles that hold the valve open, preventing the leaflets from prolapsing inwards, and allowing blood to fill the ventricle. The chordae tendineae play an integral part in the dynamics of blood flow in the heart, but still aren’t the cause for that “tugging,” or feeling of sadness.

The heart as a whole, however, is tied to emotion. When you have strong or sudden feelings, a cascade of reactions happens in the body. Stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline are released, the heart rate increases quickly, and blood pressure rises. You do “feel” that in your heart. In fact, there have been numerous studies looking at cardiac physiology in response to various emotional states. One area of research has found that the suddenness of experiencing strong emotions can have cardiovascular effects like heart attacks or strokes. An article from 2018 showed that persistent strong negative emotions and stress are highly prognostic for heart disease. Conversely, positive emotions were associated with better heart health.

So, whether it’s a sad melody, or the story of a loyal dog — it’s true that your emotions are felt (in part) in your heart. Perhaps you should say tugging at your heart. But that doesn’t sound quite as poetic.