O sleep! O gentle sleep! / Nature’s soft nurse, how have I frightened thee, / That thou no more wilt weigh my eyelids down / And steep my senses in forgetfulness?

Henry IV is not one of the Bard’s most memorable plays. I think it once lulled me to sleep. But these lines speak of insomnia, a common problem that begs for a solution. There is no shortage of advice. Count sheep. Drink warm milk. Feast on turkey. Take melatonin pills. Take kava-kava. Try valerian root. Mix up a drink from a special powdered blend of pumpkin seeds and dextrose. Listen to recordings of chirping crickets. Settle down on a mat embedded with amethyst crystals. Relax on a “Polar Power Mega-Field Slumber Pad” designed by Dr. William Philpott whose last name rhymes with a term that can be used to describe his ideas about treating disease.

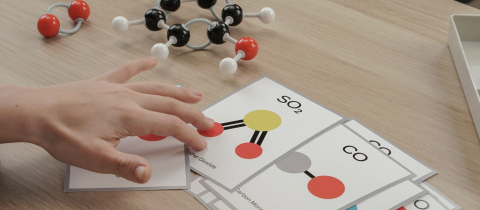

Virtually all diseases, Philpott maintained before he left us, could be managed or reversed with magnet therapy. Of course you had to have the right type of magnet. Only those that were capable of producing a “negative magnetic field” were therapeutic since “only these can promote an oxygen-alkaline rich environment within the body.”

That environment doesn’t come cheap. Philpott’s miraculous pads are still being sold for hundreds of dollars. But instead of focusing on the claptrap of negative magnetic fields, let’s look at something that may actually have a positive effect. Like that mixture of pumpkin seed powder and dextrose.

First, we need to do a little travelling back in time to the 1970s and the lab of MIT neuroscience professor Richard Wurtman. Unlike Philpott’s random ramblings, Wurtman’s research is backed by hundreds of peer-reviewed publications that have established him as one of the world’s leading authorities on chemical activity in the central nervous system.

It was Wurtman who demonstrated that levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain respond to dietary manipulation. This is of importance because higher serotonin levels have been linked with anti-anxiety effects, appetite suppression and sleep enhancement.

Serotonin is formed inside cells from the amino acid tryptophan, a component of most dietary proteins. When some questionable info emerged about turkey containing high doses of tryptophan, the lay press was ready to jump. Turkey became a remedy for insomnia and even made an appearance on a Seinfeld episode in which Jerry and George conspire to put Jerry’s current girlfriend to sleep by overdosing her on turkey so that they can play with her collection of antique toys.

Actually, turkey protein does not have more tryptophan than other meat proteins. In any case, as Wurtman demonstrated, tryptophan levels cannot be increased by eating more protein. That’s because amino acids are ferried across the blood-brain barrier by transporter molecules that have less of a preference for tryptophan than for the other amino acids that make up proteins.

However, should a tryptophan-containing food be coupled with a source of carbohydrates, levels of tryptophan in the brain, and consequently serotonin, will rise. This happens because carbohydrates stimulate the release of insulin, which prompts the absorption of amino acids into muscles.

But here, too, tryptophan is absorbed less efficiently, meaning that with the competing amino acids being driven into muscles, more tryptophan is available for absorption into the brain. Eating a turkey sandwich, with the bread providing the required carbs, actually makes some sense.

While serotonin may have a calming effect, it doesn’t actually induce sleep. The hormone melatonin, however, does. And it is made in the brain’s pineal gland from serotonin. This reaction, however, is inefficient as long as the eyes are stimulated by light. But with darkness, conversion of serotonin to melatonin begins and drowsiness sets in. The formula for sleep would then appear to be coupling darkness with a source of tryptophan and a carbohydrate that stimulates quick insulin release.

Wurtman’s research prompted Canadian psychiatrist Craig Hudson to investigate the possibility of a commercial product designed to increase melatonin levels. He knew that melatonin supplements were available, but evidence indicated that when taken in a pill form, the hormone has a short half-life. Hudson’s idea was to try to induce a normal sleeping pattern with a more continuous release of melatonin.

First, he needed a good source of tryptophan and found it in the seeds of a specific variety of pumpkin. He then mixed the powdered seeds with glucose, the archetypical insulin releaser. A bit of natural lemon or chocolate flavour, and “Zenbev” sleep-enhancer was born. It hit the market after a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial showed that subjects with sleep problems were able to reduce the time spent awake during the night. Admittedly, a single study is not very compelling, but there seems to be no risk giving Zenbev a shot.

Neither is there a risk, outside of a possible allergy, in eating two kiwifruits an hour before bedtime. That’s right, kiwis may help with sleep problems. In a study of 24 subjects, sleep onset, sleep duration and sleep quality were significantly increased with kiwi consumption.

But why study kiwis at all in this context? It turns out that the fruit is a source of serotonin. Although the authors declare no conflict of interest, they do acknowledge support from Zespri International Ltd. A quick Google search reveals that Zespri is a marketer of kiwifruit. That of course does not invalidate the study, but it would be comforting to see the trial duplicated by a totally objective research group. In the meantime, there’s no harm in giving the kiwi regimen a shot. Serotonin aside, kiwis are a great source of antioxidants and folate.

And if Zenbev or kiwis don’t lull you to sleep, you can indulge in a cup of decaffeinated Counting Sheep Coffee. It contains valerian root extract, which does have a history of use as a sedative. During the Second World War in England, it was even used to relieve the stress of air raids.

But as far as this coffee goes, we just have to take the marketer’s word for its sleep-inducing effect. That, though, coupled with an appearance on television’s Dragon’s Den, seems to have been enough to perk up sales.

And that should make the investors in Counting Sheep Coffee sleep better.