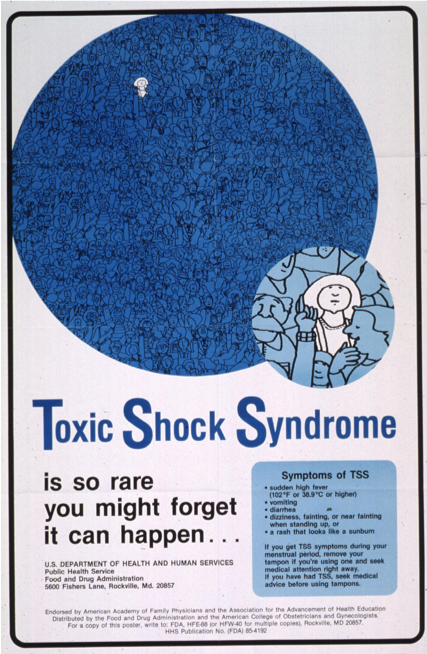

In the early 1980’s and 90’s toxic shock syndrome was on everybody’s mind. Its prevalence dominated headlines, inspiring fear in every tampon-using woman across North America. Young adults going through puberty were taught to watch out for toxic shock syndrome like it was hiding beneath every tampon wrapper.

My mom, going through puberty in the mid 80’s, was inundated with warnings to not leave tampons in too long and to always pay attention to new or unexplained rashes. But by the time I hit puberty in the early 2010’s the flood of warnings had slowed to a trickle. I was made aware that toxic shock syndrome was a risk, but also that it was rare, unlikely and treatable. Almost a decade later I don’t think I’ve heard the words toxic shock syndrome in years.

So what happened? How did people stop dying of toxic shock syndrome, or if they didn’t, why did we stop hearing about it?

What is toxic shock syndrome?

Toxic shock syndrome or TSS is an infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus, the same bacterium responsible for “staph infections” on the skin.S. aureusis normally present in human’s respiratory tracts and on their skin, but it’s what’s called an opportunistic pathogen. Given an opening (a compromised immune system or an injury on the skin),S. aureuswill infect its host, causing all sorts of nasty effects from pimples to pneumonia.

Toxic shock syndrome or TSS is an infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus, the same bacterium responsible for “staph infections” on the skin.S. aureusis normally present in human’s respiratory tracts and on their skin, but it’s what’s called an opportunistic pathogen. Given an opening (a compromised immune system or an injury on the skin),S. aureuswill infect its host, causing all sorts of nasty effects from pimples to pneumonia.

TSS is a condition resulting from an S. aureus infection. It can occur because S. aureus contain what are called superantigens. Antigens are substances that T-cells (a type of white blood cell and main player in our immune systems) bind to. Normally, some T-cells bind to antigens and then display them on their surface, to show other T-cells that the infection is being dealt with. Superantigens, however, skip this displaying step, causing more T-cells than usual (or necessary) to be activated.

These activated T-cells then go on to release cytokines, little proteins that cause inflammation. Normally, inflammation is actually a good sign. It’s the result of the body increasing blood flow to an injured area in order to heal it. But too many T-cells release too many cytokines which cause too much inflammation in a process called a cytokine storm. As the name suggests, it’s not good. Cytokine storms are associated with fevers, fatigue, nausea, rashes, diarrhea and dizziness, which are also the symptoms of TSS.

TSS is a tampon disease, right?

In 1983 over 2,200 cases of TSS were examined, and it was determined that 90% of the patients were menstruating when they fell ill. Of these menstruating patients, 99% of them were using tampons.

But TSS is not exclusive to tampons. It was first identified in five non-menstruating boys and girls in 1978. From 2001 to 2011 there were 11 cases of TSS associated with bandages used to treat burns in children, and in 2003, a man died as a result of TSS after having tattoo work done.

It’s estimated that 25-35% of TSS cases are unrelated to menstruation. These cases of nonmenstrual TSS can be caused by S. aureus or by Streptococcus pyogenes, and have a mortality rate 6 to 12 times higher than menstrual TSS. While the incidence of menstrual TSS has fallen sharply since its heyday in the 80s, the incidence of nonmenstrual TSS has remained essentially constant.

If nonmenstrual TSS is more prevalent and more dangerous, why do we only associate TSS with tampons?

Well for one, because the nonmenstrual TSS is still fairly rare. With an incidence rate of 2-4 cases per 100,000 people, nonmenstrual TSS is less common than dysentery (5.39 cases per 100,000) or Lyme disease (8.3 cases per 100,000).

Mostly, though, we don’t hear about nonmenstrual TSS because of the epidemic of menstrual TSS that took place in the early 80s.

Modern tampons were first patented in 1931, but not produced until Gertrude Tendrich bought the patent in 1933. They didn’t rise to mainstream popularity until WWII when women entering the workforce began to use them en masse.

Those tampons, marketed largely by the same brands as today (Tampax and o.b.), were made of cotton and rayon and were fairly similar to the tampons of today. One brand, however, decided to explore other materials to make their tampons more absorbent.

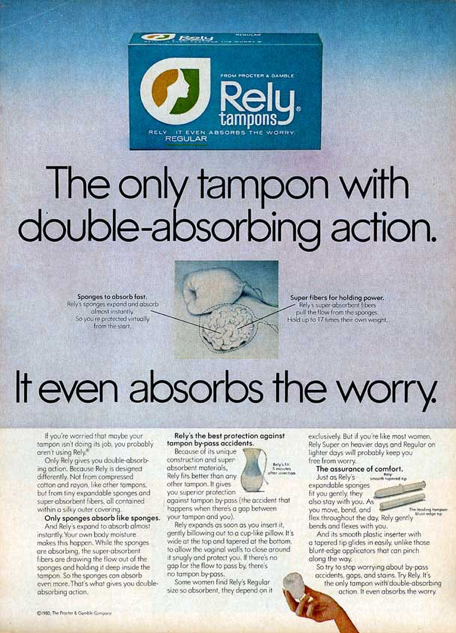

Rely tampons utilized compressed polyester beads and carboxymethylcellulose instead of cotton. These tampons were super-absorbent, holding nearly 20 times their own weight in blood, and opened inside the vagina to form a sort of cup to help prevent leakage. While these sound like fantastic features for a tampon, they turned out to also be fantastic features for a bacterial infection.

Menstrual blood is not as acidic as the vagina normally, so during menstruation the pH of the vagina is raised, which can hinder its ability to kill bacteria. But that shouldn’t matter, so long as there are no cuts inside the vagina for bacteria to enter, right?

Well, the super-absorbent nature of Rely tampons meant that the vagina was left much dryer than usual. This caused tiny ulcerations to form when tampons were inserted or removed, giving bacteria the opening they needed. Couple this with the fact that people could leave Rely tampons in for longer (thereby maximizing the bacteria’s time to grow and infect) and you have the epidemic of TSS that occurred in 1980.

Rely tampons were recalled on September 22nd 1980, but cases of TSS kept occurring. It wasn’t until 1984 that researchers realized that TSS was associated with the use of any high absorbency tampon, cotton or polyester.

I don’t want TSS! What should I do?

First, don’t panic. TSS is really rare. While several high profile cases of TSS have occurred recently, the rates of TSS are lower than ever.

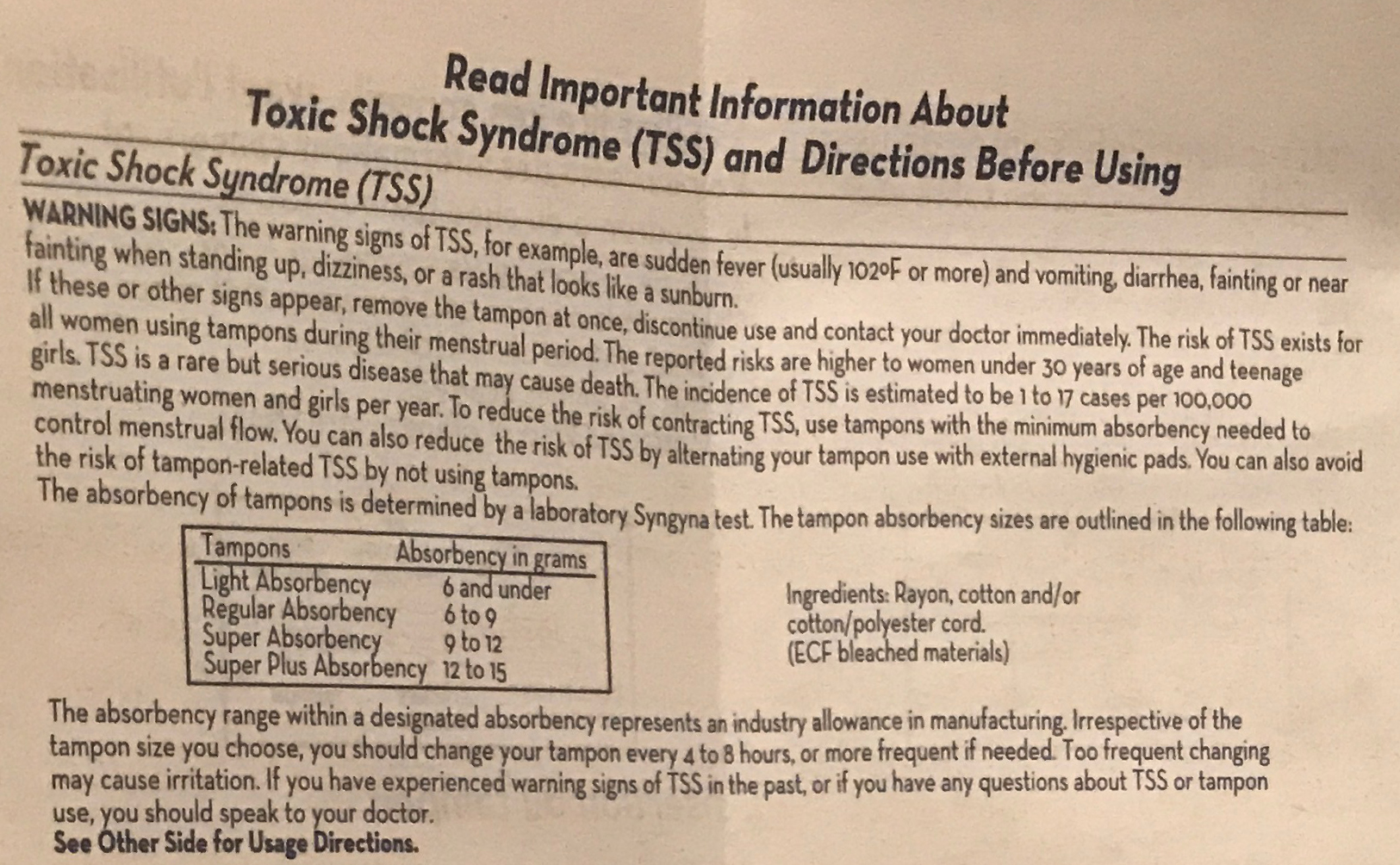

Tampon companies and government agencies have worked together to identify a strategy of use that minimizes your risk. Their recommendations are as follows:

- Use the lowest absorbency tampon that you can.

- Change your tampon every 4-8 hours.

- Wash your hands before inserting a tampon.

- Do not use tampons when you’re not on your period.

Can’t I just use a menstrual cup to avoid any risk of TSS?

Menstrual cups lessen the risk of TSS, but they don’t eliminate it. While it’s true they don’t absorb any blood, and therefore don’t cause vaginal dryness leading to ulcerations, they can be really difficult to put it, especially for new users, leading to scratches or cuts on the vaginal wall.

Menstrual cups lessen the risk of TSS, but they don’t eliminate it. While it’s true they don’t absorb any blood, and therefore don’t cause vaginal dryness leading to ulcerations, they can be really difficult to put it, especially for new users, leading to scratches or cuts on the vaginal wall.

Case in point, a 37-year-old woman was diagnosed with TSS in 2015 after using a menstrual cup for the first time.

If you’re not going to change your tampon every 8 hours, you should consider a menstrual cup. They are approved by Health Canada to stay in the vagina for up to 12 hours at a time, making them great options for those who work 8-hour days or are just forgetful.

But do still remember to wash your hands before inserting the cup, and make sure to sanitize it between cycles.

If you’d like to learn more about TSS, click here for a short but very informative video.

Want to comment on this piece? View it on our Facebook page!