The Honey Bee (known in Latin as Apis mellifera) is a species that was introduced into Canada from Europe but is incapable of naturalizing in Canada due to the harsh winters throughout most of the country. These bees only exist here as colonies managed by fruit and vegetable farmers or apiculturists (bee farmers) for the pollination services they provide as well as for their yummy honey.

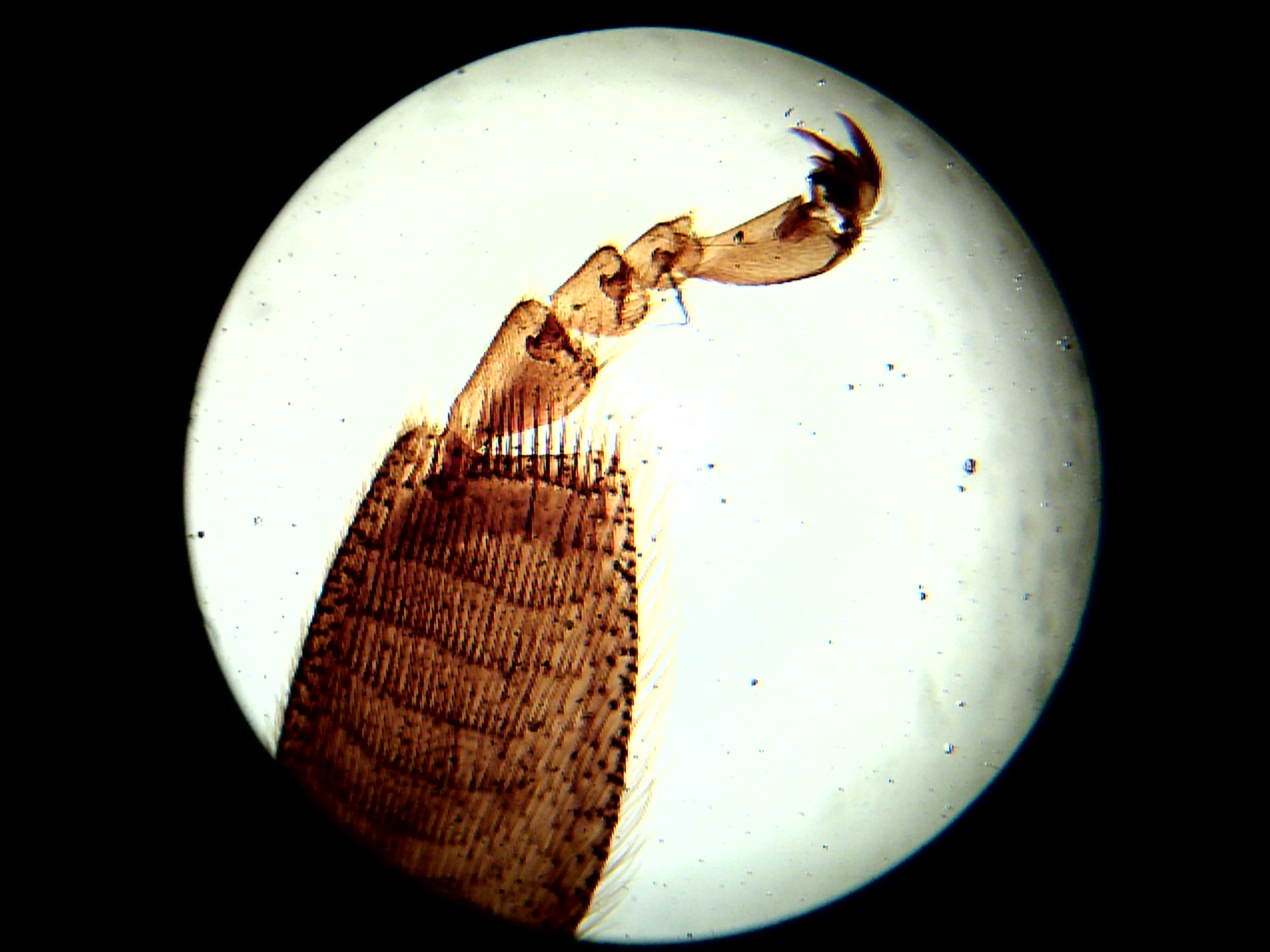

Because this species is so easy to manage, is reasonably docile for a stinging insect, and produces a rich bounty of melliferous syrup, it is estimated that Honey Bees are involved in the pollination of around a third of our food crops. Bees have hairs on their limbs (as shown in the photos) that facilitate pollen collection. Some species even have a special cavity in their tibias surrounded by hairs called a pollen basket for transporting their food.

Of course, it would be an economic and nutritional catastrophe if we were to lose Honey Bees from our fauna from one day to the next. The exact causes of the recent Honey Bee decline, or Colony Collapse Disorder, is not known, although neonicotinoid pesticides are suspected to be at play. While we would certainly be prudent to be cautious about using the neonics, they are more likely to be the straw that broke the camel’s back, rather than the smoking gun in this case. Honey Bees that are managed commercially for agricultural pollination have been experiencing health problems for decades, in part as a consequence of the hives being reared in industrial conditions and transported from farm to farm. As social animals, Honey Bees get easily stressed and one consequence of that is a weakening of their immune systems, making them more prone to infection by disease and attack by parasites.

However, insect pollinators come in many shapes and forms, many MANY shapes and forms. In fact, there are over 20,000 species of bees in the world, 1000 of which are in Canada. This large Super-Family of insects (called Apoidea in Latin) includes the Honey Bee, but also Bumble Bees, Mining Bees, Sweat Bees, Digger Bees etc. To most people, these bees (other than Honey and Bumble ones) go unnoticed... but they are out there. However, there are also other important groups of insect pollinators, including the Hover Flies, the ones that look like bees and wasps in order to fool their predators into leaving them alone at the flowers. There may be another 1000 species of these effective pollinating flies in Canada alongside the bees. This is not to mention the butterflies and beetles that act as important pollinators of Canadian flowering plants as well.

With so many species of potential insect pollinators around, you would think it unnecessary to go to the trouble of hiring or raising managed Honey Bees around farms to ensure the pollination of our crops. Unfortunately, the native pollinators are often notably absent from where they are needed most due to a number of practices all too common in large-scale agricultural farms. Conventional farming typically goes hand-in-hand with a large acreage of monoculture crops that facilitate planting, weeding and harvesting but that leave no room for wildlife to live nearby. Add to that the widespread use of pesticides that impact insect pollinators and pests alike, we can see how the use of managed pollinators becomes a must when there is no way for a native one to survive.

Different kinds of pollinators feed on different kinds of flowers, relationships that are mostly dictated by the kinds of mouthparts on the insect and the shape and depth of the floral tube or corolla. Generally speaking, bees and butterflies have long probing tongues and favour flowers that have deep bell- or tube-shaped corollas, whereas flies and beetles have short and lapping mouthparts, requiring open or bowl-shaped flowers for them to be able to feed on pollen and nectar within.

As a consequence, a committed pollinator gardener will find that it is important to think carefully about what flowers to plant and to ensure enough floral diversity to feed the whole pollinator community. Often the real issue is overlooked, as our pollinator problem is not simply a Honey Bee one. When we are planting our pollinator gardens, we need to be thinking more about the conservation of native pollinators, not the managed ones.

Sure the apiculture industry has some challenges to work out, but wildflower habitat is not their principal concern.... it may very well be a top priority for the conservation of native pollinators though. Research has shown that if we reintroduce habitat for pollinators, including flowers but also nesting and overwintering sites, refuge from the weather and predators and other important features of habitat for native insect biodiversity, that they respond favourably to that and their populations increase.

@AdamOliverBrown and @AdaMcVean

Want to comment on this article? View it here on our Facebook page!