Our session on 13 July was an initial exploration of the relationship between real architecture and race. The two main intentions were to consider how to read architecture through race and how to see and resist racism in the built environment. Those are skills we all need as architects and researchers.

The first reading, by Louis Nelson and Maurie D. McInnis, looked at the architecture of racism, that is buildings constructed from racism, and how those buildings made non-white people invisible. The book chapter is recent and is a model of excellent research using primary sources.

The second reading, by Amanda Hurley, was about an architecture of anti-racism. Because we were privileged to host architect David Adjaye as the Azrieli lecturer in 2017, our focus was his firm’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. I also visited the museum in Washington DC last fall and had been thinking about it a lot. Hurley’s piece is a model of criticism because it reviews other columns—it is almost like a literature review—thus acknowledging the role of racism in architectural criticism.

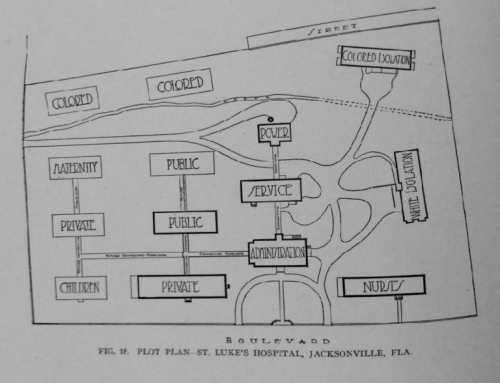

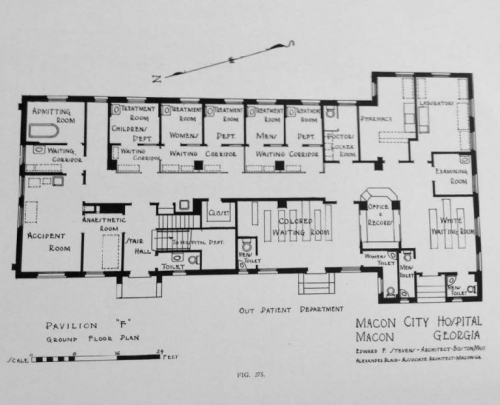

The session proceeded with a presentation of a dozen or so images meant to provoke discussion. The images were a wide range of building types, from Jim-Crow era hospital plans that boasted separate entrances and waiting spaces for Black patients, to convents, World’s Fairs, banks, churches, land-use surveys, suburban family rooms, highways, and architecture schools.

Questions we posed for the discussion:

- Nelson and McInnis, among others, have shown things how we take everyday spaces for granted. Their example is the corridor. What other architectural elements come to mind?

- Land acknowledgements can be an initial step towards addressing problematic histories: How can design make this acknowledgement a visible part of a building’s layout and symbolism?

- When considering the position of subjects in urban space, how might we re-assess visibility, hierarchy, domination? Whose actions are celebrated? Symbolism does not remain in a built object. How do its messages translate spatially to the public sites where monuments stand? Whose land ownership and sense of belonging do they claim?