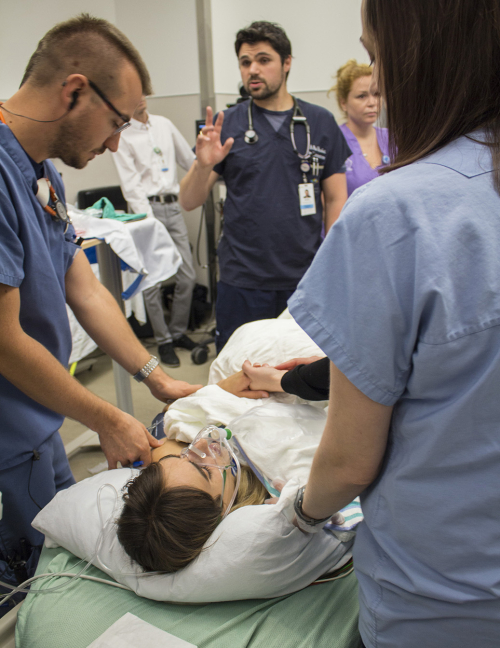

"My baby! Where’s my baby?” Pale and frightened, the young woman who has just given birth wails tearfully as she writhes in pain on her emergency stretcher.

Despite exhaustion, her shrill cry rises above the beeping monitors and the commotion in the JGH Emergency Department’s Resuscitation Unit. Tightly clutching the hand of her partner, the mother gazes pleadingly at the doctors and nurses who encircle her stretcher, newly blood-spattered from a difficult birth.

Then she overhears a nurse’s remark to the team that’s looking after the infant: “The baby’s not crying or breathing. We’ll need to initiate neonatal resuscitation!”

“My baby! My baby!” screams the mother, realizing the gravity of the situation and recalling what she’d glimpsed a few moments earlier. “Why is my baby blue?!”

Then without warning, she begins to hemorrhage from the birth canal. The Emergency and Obstetrics teams now focus intently on her, as they work to control the bleeding, under the guidance of Dr. Paul Brisebois, the Emergency physician in control of the situation, who unites the team with frequent verbal medical summaries.

Meanwhile, after a swift intervention by personnel from Neonatology and Respiratory Therapy, the infant is stabilized, put on a respirator and prepared for transport to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

And then… In the blink of an eye, it’s over! A ripple of spontaneous applause breaks out, as members of staff smile broadly, sigh with relief and pat one another on the back.

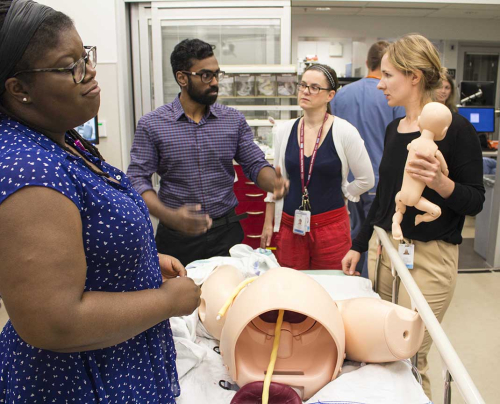

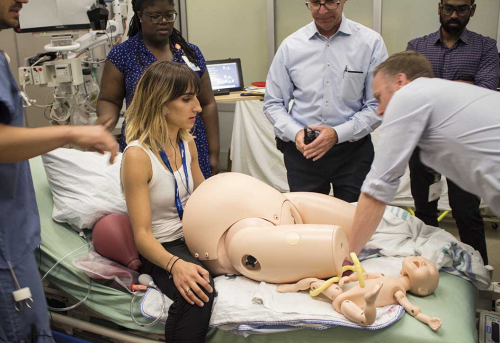

The young mother removes her oxygen mask, runs a hand through her sweat-dampened hair and hops off the stretcher—her role as a patient now finished. Behind her she leaves the plastic, life-sized, pregnancy-shaped PROMPT ™ abdomen. Its yellow plastic umbilical cord and red placenta sit atop sheets stained with splotches of ketchup and food colouring. The baby, a plastic manikin, lies silent and immobile in the emergency warming unit that, minutes earlier, had been keeping it “alive”.

On this morning in mid-June, staff from a wide range of specialties have been immersed in a simulated, yet remarkably life-like scenario headed by Dr. Errol Stern, an Emergency staff physician and Director of the JGH Emergency Medicine Simulation Program.

Months of preparation

Though the simulation lasted a mere 20 minutes, it required two months of meticulous preparation. Not only did a large multi-disciplinary team plan every aspect of the exercise, its members had to balance and satisfy the learning objectives of each of the participating healthcare specialties.

“The primary objective was not to emphasize the medical specifics of this case, in which a mother is brought to Emergency, gives birth to a non-breathing baby, and then suffers a post-partum hemorrhage,” says Dr. Stern.

“Rather, the goal of the simulation was to look at how the various healthcare teams function, how they interact in rare, stressful situations, and how the quality of their treatment and care can be improved.” (Certain of the elements in this scenario were borrowed from an actual event at the JGH last year.)

The way to do that is by amping up the pressure: start by having a pregnant woman go to the Emergency Department, where a precipitous, high-risk birth is not common. Then, have the life-saving procedures performed by coordinated healthcare teams in the confines of a single resuscitation room.

In order to determine how everyone functions in conditions which Dr. Stern describes as “controlled chaos,” it is necessary to create a scenario that involves numerous hospital departments and disciplines, with nurses and doctors from Emergency, Obstetrics/Gynecology and Neonatology, as well as paramedical personnel including respiratory therapists, unit agents, orderlies and security staff. Input is also sought from Quality and Risk Management, Information Technology (IT), Telecommunications, and Audio-Visual Services personnel.

Another challenge is to see how personnel perform outside their comfort zone, explains Melanie Sheridan, Clinical Nurse Specialist in the Emergency Department. “While members of staff cope smoothly in their own departments, where familiar facilities, equipment and healthcare workers are close at hand, how do they fare when called upon to work in a crisis in unfamiliar surroundings?”

In addition, to determine how the staff interact with a same-sex spouse, Andrea Willett, a Nursing Care Counsellor from the Family Birthing Centre, is enlisted to be the partner of the mother, played by Emily Churchill-Smith.

“Medical or nursing knowledge is not really what’s being evaluated or assessed,” Dr. Stern told the participants in a briefing session shortly before the simulation got under way. “What we’re really looking for is how individuals work together, and how teams interact in the same scenario.

“As individuals, we’re good. As teams, we’re even better. And if we can function effectively as multi-disciplinary teams, we’re truly the best. With this simulation exercise we need to explore ways of working together with the common goal of helping patients.”

Before the session, Dr. Stern cautioned the participants that their performance “may not be optimal, because the scenario was intentionally designed to be challenging. That’s okay, as we all know that everyone who participates in this simulation is intelligent, motivated, cares about doing his or her best, and wants to improve.”

Different types of simulations

Normally, Dr. Stern runs scenarios in a simulated environment at the JGH, where training is currently provided to residents and nurses in Emergency Medicine and Internal Medicine. (Dr. Stern is hoping to expand the Simulation Program to include other departments.) In this simulated, critical-care hospital room, a sophisticated, high-fidelity manikin and monitor are remotely manipulated to exhibit a variety of conditions and symptoms, to which the trainees must respond. To enhance the realism, the manikin speaks to the trainees, thanks to a hookup with a supervisor in a nearby control room.

Like the June scenario, the aim of these simulations is to offer participants an opportunity to examine and reflect upon clinical and communication skills, with responsive debriefing that promotes learning rather than criticism.

Dr. Marc Afilalo, Director of the JGH Emergency Department, highlights how this simulation differs from prior sessions: “Firstly, it took place in the Emergency Department and not in an artificial environment. Secondly, the patient was a real person and not a manikin. And thirdly, the participants were not medical residents, but experienced hospital staff members intent on identifying potential latent deficiencies in the delivery of care to our patients, so that we can focus on corrective action.”

“Whenever a serious event occurs in the hospital, a follow-up review is always conducted to determine how to prevent similar incidents from recurring,” says Krystle North, a Quality Advisor in the Department of Quality and Risk Management. “However, simulation takes it one step further. Re-creating a serious event, with obviously much less risk, is a great way to close the loop in solving these problems.”

But if the participants know they’re in a simulation (even if they aren’t informed of the details in advance), can they be expected to react realistically when called upon to treat a simulated patient with a plastic pregnant abdomen and a baby manikin?

As the June exercise demonstrated, the answer is Yes. “In these situations,” Dr. Stern explains, “members of staff become so emotionally absorbed in the event that the lines between simulation and reality become blurred, and they approach the scenario as if it were real.”

Dr. Haran Balendra, an attending physician in the Emergency Department, notes, “People really get into character and take it very seriously. At the end of a simulation session, I’ve heard them say, ‘Wow, that was so realistic! I can’t wait for the next one!’”

Assessing the simulation

Within minutes of concluding the simulation, about 55 members of staff—40 in a conference room in Pavilion K, with a video hookup to ten in Emergency and another five in Obstetrics—met for more than an hour to exchange impressions of what they’d just experienced.

From the perspective of the patient experience, Ms. Churchill-Smith said that despite the frenzied activity in the Resuscitation Unit, “people were very attentive to me and were clearly focused on my baby’s well-being.” She was also reassured that after her baby had been intubated and was breathing more easily, she received information promptly about the infant’s condition.

Ms. Willett, the simulated patient’s partner, noted that members of staff treated her respectfully and acknowledged her connection to the patient. However, she added, she was asked only for basic information about the patient, even though there was much more background that she was prepared to provide.

During the frank and wide-ranging debriefing, staff covered topics such interdisciplinary team communication and medical management, the need for use of the infant warming unit to provide temperature regulation for critically ill newborns, the additional role of respiratory therapists who are also trained in neonatal resuscitation, and the specific personnel who respond to a Code Lavender, the code which is called when there are neonatal emergencies.

In summing up, Dr. Stern thanked members of staff for the time they had devoted to the lengthy preparations for the event, as well as their participation in a scenario of such unprecedented complexity at the JGH.

“This was our first in situ simulation in Emergency,” he said, “and hopefully, it was the beginning of many more to come."

This article was originally published in JGH News.