Denial. Anger. Bargaining. Depression. Acceptance.

This group of terms has become so ingrained in our cultural consciousness that almost anyone could tell you what they are: the five stages of grief.

Introduced to the world in the 1969 book On Death and Dying by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the Kübler-Ross model (sometimes called the DABDA model) surmises that there are sequential stages of various emotions that a patient goes through when diagnosed with a terminal illness, starting with denial and ending with acceptance.

Wait, did you think that the five stages of grief were experienced by the loved ones of a recently deceased person? So did I until researching this article! In reality Kübler-Ross developed her stage model after interviewing many individuals with life-threatening illnesses. It was only the experiences of these patients that she attempted to model.

While she was a psychiatry resident in New York, Kübler-Ross realized how little attention was paid by hospital staff to terminally ill patients, and how little medical knowledge there was regarding the psychological aspects besetting patients facing death. She worked extensively with terminally ill patients throughout her medical school career and continued to study and teach about such topics when she became a professor at the Pritzker School of Medicine.

Using these experiences Kübler-Ross wrote her now famous book outlining the DABDA model, citing her contact with ‘‘over two hundred dying patients’" as its basis. Now, she did write in On Death and Dying that, “family members undergo different stages of adjustment similar to the ones described for our patients,” but having a loved one diagnosed with a terminal illness is not the same as losing said loved one to death. The five stages of grief were never meant for the bereaved. That’s just how they’ve been applied again and again.

Putting aside that this model has been seriously misappropriated throughout the last few decades, it’s important to realize that from its conception, the Kübler-Ross model of grief was not based on empirical or systematic investigations. It was essentially “a collection of case studies in the form of conversations with dying patients.”

I asked our OSS colleague, Dr. Christopher Labos, to define case studies in one sentence, and he sent me this: “It’s a description of what happened to a single patient. It’s an anecdote.” As we are hopefully all aware by now, anecdotes are the lowest form of evidence. They cannot stand on their own. Kübler-Ross saw many patients and gathered many anecdotes, and then used them to create a scientific model that simply is not based on good evidence.

Comic source

Since the publication of On Death and Dying, a few studies have attempted to test the stage theory’s validity empirically. Most of the results have found it lacking. This 1981 study looked at 193 individuals who had been widowed for various lengths of time. Their results indicate that “the stresses of widowhood persist for years after the spouse's death; they do not confirm the existence of separate stages of adaptation.” Work by Bonnano in 2002 looked at 205 individuals before and after their spouses’ death, and found that only 11% followed the grief trajectory assumed to be “normal”.

Many of the studies whose findings do support the existence of a stage theory of grief have suffered from serious methodological problems. Take for example this 2007 study that examined 233 bereaved individuals. After its publication, several letters to the editor critiqued its design and findings, and the authors later undermined their own conclusions by suggesting relabeling and reconceptualizing the stages of grief.

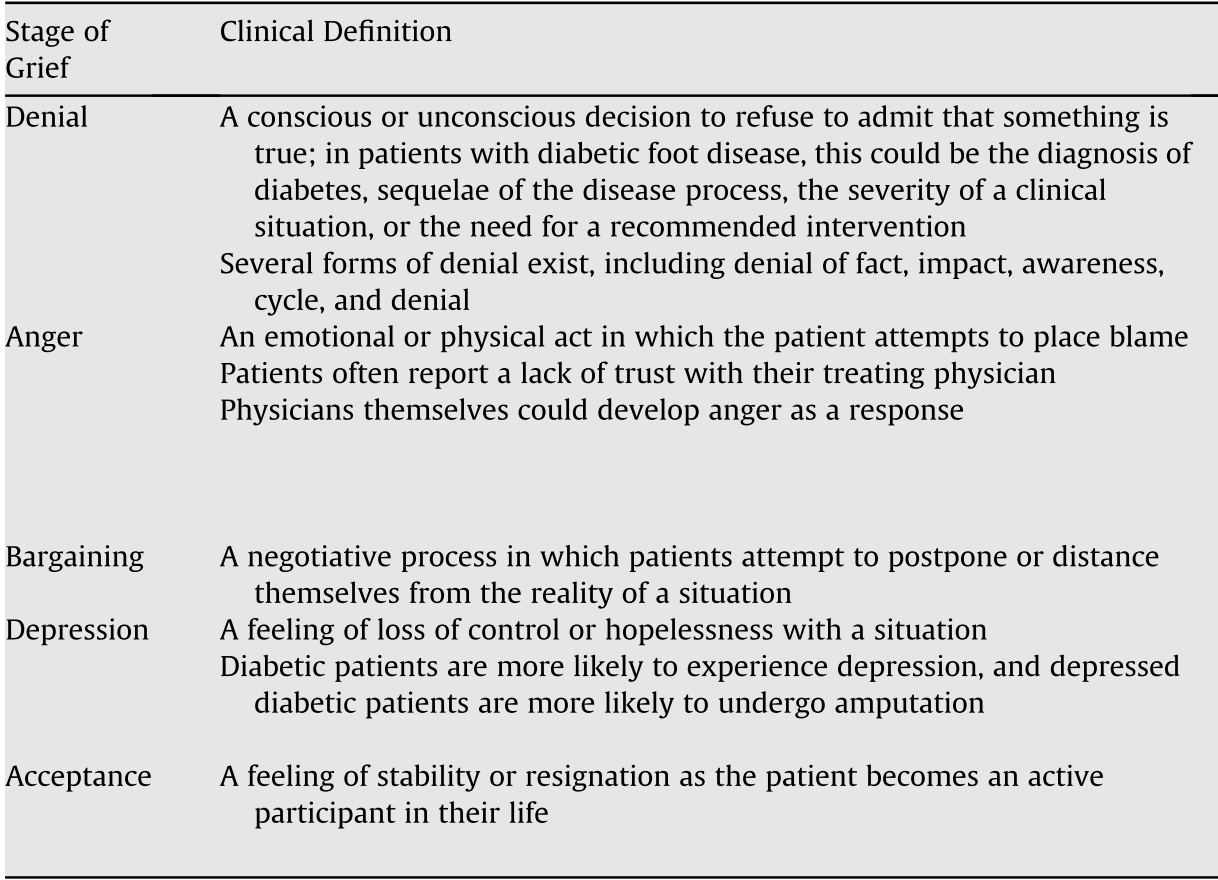

Despite the lack of evidence to back up the Kübler-Ross stage theory of grief, its original birthplace, On Death and Dying, has been cited 15 509 times on Google Scholar at the time of writing. It has been applied to everything from the grief processes of those diagnosed with diseases like COPD or HIV, to the grief experienced by caregivers of those with dementia; patients who have amputations due to diabetes; doctors who receive low patient satisfaction scores or go through reduced resident work hours; even (and I am not making this up) the grief experienced by consumers after the iPhone 5 was a disappointment.

Why are we, scientists and the general public alike, so eager to believe in this non-evidence-based model?

Having experienced the sudden and tragic loss of my mother only six weeks ago, I can personally attest to the time following a loved one’s death being confusing, overwhelming and desperate. During such a harrowing time, narratives like the five stages of grief can bring immense direction and comfort to your life. Emotions like anger or even acceptance can feel inappropriate and having an outside force like the Kübler-Ross model affirm and validate your experience can really help you cope with your feelings.

To put it another way, “we are pattern-seeking, storytelling primates trying to make sense of an often chaotic and unpredictable world." The narrative of the Kübler-Ross model reminds us that whatever we’re feeling now isn’t permanent. It essentially guides us through a difficult time and assures us that eventually we will reach acceptance and be OK. Assuming your experience lines up well with the five stages, you’re given a sense that you are managing your grief in the “right” way. That you’re doing well. But that’s exactly the problem.

Not everyone experiences grief in the same way. But in addition to dealing with the loss of their loved one, those whose experiences do not follow the Kübler-Ross model must contend with the idea that there is a right way to grieve and that they’re not following it.

The five stages model was meant as descriptive but has become prescriptive. Bereaved individuals can feel like there are certain reactions they should be having, and that they are somehow grieving wrong by not having them. There is no set pattern of emotions that must be experienced to come to terms with death, and we can seriously harm bereaved individuals by comparing their experiences to a non-evidence-based, not-even-meant-to-describe-their-experiences model.

One year after her own death in 2004, a new book by Kübler-Ross and David Kessler was published. In this book, Kübler-Ross remarked that the five stages are “not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or goes in a prescribed order.” If these five stages are not universal (and indeed how could they be, given the huge differences between cultures in regard to their grieving processes?), or even sequential, why they’re conceived of as stages is a mystery to me.

It is time to realize that grief takes countless forms, is experienced in limitless ways, and cannot possibly be explained by a simple five stage model. When we push this narrative as universal, we alienate those for whom it doesn’t apply and only cause them more pain in an already painful time.

There is no right way to grieve. There is no wrong way to grieve. And I hope that when you experience grief you can take some small comfort in knowing that how ever you’re feeling is just fine.

Want to comment on this article? View it here on our Facebook page!