Findings and Analysis

5.1 Introduction

A study of the physical spaces in village housing with special emphasis on women's activities and use/avoidance of these spaces forms the essence of the field research. In this chapter the findings from the field research will be presented. Social and spatial aspects of gender segregation are described and analyzed to establish a pattern of women's use of space. At first, however, some relevant facts about Bangladesh are introduced as a background for the field study.

5.1.1 Bangladesh - Background

Bangladesh is one of the least urbanized nations in the world, with 90% of its population living in rural areas. If we consider women exclusively, they are even less urbanized. 95% of women live in villages. The total area of Bangladesh is 142,776 sqkm and the population according to the 1990 census is 112 million. Poor in mineral and power resources, Bangladesh is mainly dependent on agriculture which is done in the most traditional way. Poverty and over-population are two of the country's main problems.

The topography of Bangladesh is basically low-lying, flat alluvial land with an extensive network of rivers and channels. Its typical monsoon climate is characterized by rain-bearing winds, warm temperatures and humidity, resulting in a lush green landscape all year round. Its geographical location renders it susceptible to heavy rains, floods, high intensity storms and tidal bores which cause immense loss of life and property year after year.

For its entire recorded history, this region has been a peasant society, whichhas provided the foundations of its distinctive culture. In addition, Bangladesh shares in two of the oldest and richest traditions. Its roots reach back in two directions, both to ancient Indic civilizations and to Islamic culture. This northeast corner of the Indian subcontinent has been influenced by successive Indian civilizations but its people have retained a certain autonomy and cultural distinctiveness - mainly because of its location outside of the mainstream, at the periphery of major cultural changes. The crystallization of the Bengali language from the classical Sanskrit during the Indian Medieval period provided the region with a linguistic underpinning for its separate cultural identity. Following the conquest by Muslim invaders from Central Asia in the thirteenth century and the subsequent arrival of Muslim missionaries, a substantial portion of the population gradually converted to Islam. This reinforced the sense of distinctiveness and eventually found expression in the demand to create an independent state, first in 1947 as the eastern province of Pakistan, and then in 1971, as independent Bangladesh.

5.1.2 Islam in Bangladesh

Islam in Bangladesh has a unique local form and identity. Conversions to Islam during the era of Islamic empires came more as a spontaneous response to the preaching of itinerant Sufi mystics and Muslim teachers than as a result of state policies encouraging such religious change. Because of the peaceful penetration of Muslim missionaries, the evolution of Islam was different from that of Northern India. In North India the spread of Islam was primarily confined to cities and urban administrative centres. In eastern Bengal, it spread mainly in the villages. Far from the cradle of Islam, with no knowledge of Muslim scriptures (which were either in Arabic or Persian), illiterate Bengali villagers evolved their own brand of Islam. Pitted against a rich but unpredictable environment, their desire to tame the cruelties ofnature distinctly affected and shaped their visions of religion and culture. As a result, many local customs, rites and rituals were incorporated into Islamic beliefs. Saint worship, belief in supernatural powers of the spirit world, belief in astrology - although contrary to Islamic practices - all are part of the rural spiritual faith.

5.1.3 Rural Settlement Patterns in Bangladesh

The majority of the population of Bangladesh live in rural settlements dispersed among the agricultural land. These settlements are characterized by two major forms, namely the nucleated or clustered settlement and the scattered or dispersed settlement. A third variant, semi-nucleated or semi-dispersed is also notable in some areas. These can take a linear pattern or clustered pattern or a combination of the two. According to the geographical, physical and social forces, we find different patterns of settlements in different regions of Bangladesh:

- Nucleated and semi-nucleated or clustered in the high flat land of the northern Piedmont and the Barind regions, Chittagong Hill Tracts and Haor areas of Sylhet

- Scattered in the central delta region, the flood plains, where homesteads are built on artificially raised mounds

- Scattered in isolated clusters in the coastal areas and offshore islands

- Linear along the levees of rivers and in the moribund delta area of the south-west region.

- Linear and sparse along the spring line in Chittagong (Fig 18)

5.2 Setting for the field study

The villages Bajitpur and Shadashivpur are located near the Indian border. The villagers are proud of the fact that it is through this area that Islam first entered Bangladesh in 1204 A.D. with the invasion by Ikhtiar Muhammad Bakhtiar Khilji. Bakhtiar Khilji established a capital in Gaur, an area about eight miles north of Bajitpur. There are several historical edifices in the area: remains of palaces and courts of erstwhile rulers, the thirteenth century walled city of Gaur and the Sona mosque of the fifteenth century.

This settlement is the place where four brothers from Shashani in Patna (India) came and established an estate in the middle of the nineteenth century. A British administrator named James Grey, out of gratitude for their generosity (they wrote off a large loan when he defaulted), conferred additional government land and the title of Chowdhury on the family. Bajitpur is named after the eldest brother Bajit Dewan, while Shampur is named after the second. The youngest brother Abdul Karim Peshkar is said to have written the first autobiography in the Bengali language.

The two villages can be reached by bus and ferry from the nearest town, which is the district capital Nawabganj. At the time of the study, the roads were at places virtually impassable due to the post-flood situation. Fortunately a four-wheel drive jeep could be found to make the journey to Kansat, a marketing centre next to Shampur Union. The river Pagla between Kansat and Shampur was crossed by boat. A two-kilometer walk through the muddy and rutted road to the research site followed.

The population of the two villages is 9,825 with 380 homesteads in Shadashivpur and 425 homesteads in Bajitpur. There are about 20 Hindu households in Bajitpur, concentrated in three paras. Although there are one or more mosques in each para, there are no Hindu temples in the two mauzas.

The river Pagla on the east separates the villages from Kansat, which boasts of a post office, a college, daily and weekly markets (Saturdays and Tuesdays) and a silk weaving cottage industry.

On the west is Chama, which also hasweekly markets (Thursdays and Sundays). The Union Council Office and a coeducational High School is located in Chama. An agricultural bank and a small electric ricemill is located in Bajitpur. The individual paras of the villages are scattered among agricultural land and mango-groves. (Fig. 19)

This region is mainly dependant on agriculture. Mango, sugarcane and paddy are the main crops. Jute, pulses, mustard vegetables, etc. are also important cash crops. There are no industries in this area. The primary occupation of most villagers is agriculture, either by direct cultivation or by commercial dealing. Other occupations include traders, teachers, health workers, artisans and businessmen.

This area is flooded about two months a year during the rainy season, but as most of the houses are built on elevated ground, they are usually above flood-level. But the surrounding countryside remains under water and the only mode of transportation is the boat. Continuous rain and rising groundwater, however, cause many of the mudhouses to crumble and there was ample evidence of this in the villages at the time of the survey due to the recent floods. Ninetysix homesteads were reported to be affected.

About fifty years ago there were single village chiefs in each of the paras, many of which are named after these chiefs (Bahadur Morol Tola, Enayet Bishash Tola, etc.) Nowadays there are three to four chiefs (matbor) in each para heading their own communities or factions which are often made up of members of the same kingroup. These chiefs are not necessarily hereditory, but elected by the villagers periodically. Their main function is to arbitrate differences in their factions, individually or by "calling a shalish (group of arbitrators)." They also advise in important family matters and take part in marriage negotiations of members of their groups.

Officially the union is governed by a Union Council board. The board consists of a Chairman and nine members, all elected. The Chairman has always been a member of the landlord family, reflecting their status in the region. The main political parties are quite active in the villages. The most influential one is the "Jamat-e-Islami," a political group with fundamental ideology. This group is active in trying to encourage and maintain Islamic rules and standards, one of which is the segregation of women.

[ TopOfPage(); ]5.3 Analysis of findings: The physical environment

5.3.1 The Settlement Pattern

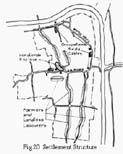

The two villages together seem to function as a single entity.(Fig. 20.) In the middle of the community is the landlords' enclave - Chowdhurypara. The rest of the socio-economic groups are scattered in different paras, which are separate linear clusters surrounded by orchards and crop-land. Rich and poor farmers live side by side - often the only way to distinguish their houses is by the condition they are in, and sometimes by their size. Some Hindu occupational groups such as the smiths, the carpenters and the milkmen have their own enclaves at the edges of the settlement.

The main public institutions - the schools, the bank and the ricemill are located on the main road and on its main subsidiary, the road along the edge of Bajitpur, parallel to the river. This road is a thoroughfare leading to other villages and in this study it will be called the edge road.

There is a very definite hierarchy of spaces in the circulation pattern. (Fig. 21) The main road (D.B.road) which runs from east to west is mainly a circulation spine in Shampur union built by the British for revenue collection purposes. This road joins two markets, one in Kansat and one in Chama. The secondary village roads which feed the individual paras branch out at right angles to the main road.

The main road runs through mango-groves, canefields and paddy fields; ditches on both side of the road act as drainage channels where children often fish. Because of its relatively high level, this road is often the only one not to be submerged during the annual monsoon. During heavy rains, however, (as for example just before the field study took place) boats instead of oxcarts ply on the D.B.road. The other vehicles used on this road are bicycles and occasional motorcycles. Only a few houses face this road; among them the three households of the village smiths, who take advantage of the commercial traffic on this road.

The secondary roads, which are the village lanes, branch off perpendicular to the D.B. road and lead into the individual paras or neighbourhoods. (Fig. 22)

Homesteads are organized in a linear pattern on both sides of the village lanes. Only the edge road has homesteads on one side. Men walk along these roads and congregate to stand and talk. They sit by the roadside to socialise or to work. Mosques and small neighbourhood shops on the roadsides also encourage social gatherings. Children play all day long in safe surroundings - there is no fear of wheeled traffic (except bicycles and on rare occasions, an oxcart). Cows kick up a dusty haze when they are led home at sunset. Women are almost totally missing from the street life. Their appearance there is conditional to necessity and to modest behaviour. Sometimes women are visible in the entrances to their homesteads, looking out at the road. Their role in the street-life is as discreet spectators, neveras participants.

The third category of roads are the network of back-lanes and footpaths at the back of the homesteads. These lanes, which are often nothing more than narrow dirt paths created by walking feet, meander through mango-groves and crop-fields and link the different paras. These lanes are used by women to get about, but men also use them to get to their fields or as short-cuts.

5.3.2 Public Spaces

Public spaces are conceived as "male spaces." (Fig. 23) Women do not visit public institutions such as the mosque or the bank. Women usually move discreetly within a cluster of homesteads or sheltered paths when men are in the fields. They avoid open fields and public roads. If women travel on foot, they must be accompanied, either by male relatives or by their children. They often shield their faces with an umbrella while travelling. The most common mode of transportation for men is the bicycle, while for women it is a covered oxcart or a covered boat. When women are going to a nearby village to visit relatives, they usually walk through the fields and mango groves at the back of the house. The D.B. road is generally not used by women, specially on hat (weekly market) days when the traffic increases. In the post-flood period, however, when many of the pathways through the fields were virtually impassable, women were sometimes forced to use the D.B. road.

The public areas can be categorized in the following manner:

Public: D.B. road, mosques, fields, mango orchards, daily and weekly markets, school, bank, ricemill

Semi-public: Village lanes, neighbourhood shops, the frontyard or goli, public handpumps

Semi-private: Back-lanes, women's pond and bathing pier

Private: The enclosed courtyard, the backyard or kanta

Women use spaces according to the order; the higher in the hierarchy, the less the spaces are used by women.

5.3.3 The Homestead or Bari

The name for the homestead is synonymous with the family name or occupation. Which bari a villager belongs to is an important factor determining his status and social standing. Although the traditional extended family structure is disintegrating under the onslaught of poverty with many members leaving the often overcrowded homesteads, they are still known as members of their original bari.

Organization

The homesteads are arranged in rows on one or both sides of the village road. The residential plots (as shown on the mauza land maps) are usually rectangular with the narrower side abutting the street. Plots are generally not demarcated by physical boundaries. The homestead is started by creating a flat mound (bhiti) for flood control. The traditional Bangladeshi homestead is an aggregation of loosely spaced free-standing units grouped around a central courtyard. In this region, however, the more compact layout with adjoining rooms, similar to the North Indian model, was also noticeable. The size and number of huts and the size of the courtyard is a good indicator of the economic condition of the family.

The total plot is not built on. The homestead is organized on the plot in a distinct hierarchical sequence. (Fig. 24) There is a fairly large transition space on the street side of the plot. This is a semi-private space known as the goli. At the back of the house is an open space with vegetation known as the kanta. The living area is made up of several huts (ghar) grouped around and facing a square or rectangular courtyard. This courtyard, known as the angina, is the heart of the homestead where most activities take place. The courtyard is entered on the street-side by the deori, the indirect entrance which acts as a visual barrier. There are one or more huts around the courtyard, which are only used for storage and for sleeping. Most huts have attached semi-open covered spaces known as baranda, which act astransitions between the open courtyard and the enclosed courtyard.

The structure and layout of the homesteads are not uniform, although certain systems of organization can be observed. The dwellings of five socio-economic groups were studied; however, according to systems of organization, the dwellings can be categorized in three main groups - homesteads of the landless, the farmers and the landlords (Fig. 25)

|  |

Each house is unique and changes with the needs of the family and reflects the pattern of its growth and modifications. Rather than a division within an enclosure, it is an aggregation of spaces. A nuclear family shares one room and an additional one is built when a son gets married. Huts can be dismantled and transported if a family member decides to move. A large courtyard is fragmented into smaller ones as the family multiplies and separates. This flexibility is inherent in the organisation of the homesteads and the transitory nature of the building materials used.

Most families are nuclear, often with single families living in separate homesteads. More common however is what may be called the semi-extended family where members of the same family share a homestead with one or more courtyard, but have separate incomes and eating arrangements. Among the landless, there is also the arrangement of several nuclear unrelated families sharing a homestead with a single courtyard. Adjacent homesteads usually belong to relatives and have interconnected courtyards. Family ties are an important determinant in the grouping and proximity of individual homesteads.

Elements

The Goli: The goli (Fig. 26) in front of the homestead mostly remains unfenced and is freely used as circulation space for people passing through. It is usually at a higher level than the street. The family uses it forfeeding livestock, keeping the haystack and receiving guests who are not close or important enough to be taken inside the house. Men usually gather here in the evenings to converse. Mobile quilt-makers, vendors and the village barber use this space to set up temporary shop. This space is considered to be "male" space, although women too use it to some extent. They use it for work that often spills over from the courtyard, for example for drying grain or to make mud storage bins. They however do not linger there for extended periods of time. Previously, women were hardly ever visible in the goli, but nowadays they can be seen there socializing with one or two other women and watching the activities on the road. However, I have seen women actually sitting in the goli on only one occasion and that was in a relatively isolated area at a time when men were at the weekly market. At other times it is obvious that they do not feel at home in this space, although it is part of their homestead.

The Baithak: In many of the homesteads, there is a long shaded porch facing the goli for receiving male guests. (Fig. 27) This is known as the baithak. In more affluent homesteads the baithak is a proper room, which is also used by the family for sleeping and/or as a study for older boys. Previously, baithaks were separate structures; the present trend is to incorporate them into the main structure. For occupational groups like the village smiths, the workshops double as baithaks where men gather to play cards in the afternoon. In some homesteads baithaks are also used to shelter domestic animals. Several related families may share one baithak even if they do not share a courtyard.

The Deori: The homestead is usually entered through a corner of the courtyard between two huts. This entrance is generally indirect with specially built walls for visual privacy. (Fig. 28) The entrance space is known as the deori.

In affluent households the courtyard has boundary walls with entrance doors that can be locked. In other households, however, the corners between the structures remain free from fencing and the entrances do not have doors. Often in poor households, the entrance is not visually obstructed by staggered walls. Nevertheless there is always an attempt to create visual barriers, either by hanging a jute-mat or old quilt in the doorway or by a movable doormade with leaves in a reed-frame. The deori acts as a buffer or filter between the public outside and the private inside. It is the "threshold" between the two domains.

The Ghar: The individual huts known as ghar are usually single- or two-room multi-functional structures used mainly for sleeping and storage. They are also used for other household activities during inclement weather. The huts are rectangular in plan and entered from the courtyard on the longer side. They are usually made of mud with overhanging sloped roofs of thatch or tile. Bamboo walls were popular in the past, but beyond the means of most villagers at present. Thatch, jutesticks or reeds may also be used for walls. In some huts there is a false ceiling which is used for storage. Corrugated iron roofs are rare but are regarded as status symbols. The structures in the landlord para are all built of brick with flat roof of burnt clay tiles supported by wooden beams. During feudal times, peasants were not allowed to build in permanent materials like brick, and to this day, there are not many brick houses other than the landlords' homes. In the typical village home, usually one nuclear family shares one room until the son grows up and marries. Then another hut is built for him. The individual huts are oriented in cardinal directions.

Furniture: In contrast to other regions of Bangladesh, there is a tradition of having some household furniture in this region. Even the poorest family usually owns a wooden bed or a string cot. Other furniture used are wooden chests and in more affluent households small cupboards and a few chairs. Jute hangers hang from the rafters to store food items, bottles and crockery. Paddy or rice are stored in mud storage bins which are usually plastered closed till they are needed. These bins and often beautifully decorated mud storage shelves are made by women. Water is stored in earthenware or brassjugs. Brass utensils are a sign of status and wealth. They also can be pawned in times of need.

Openings: The mud huts often do not have any windows and only one doorway as a source of light. If there are windows present, they are very small, usually only a horizontal slit or round narrow holes. The reason given for absence of windows or for their small size is visual privacy and more importantly, a safeguard against evil spirits entering the room. In more affluent homes, windows are larger, often with wooden shutters. The shutters or wooden flaps are in four parts, so that the lower two can remain closed during the day to ensure privacy. (Fig. 29)

Baranda: The baranda is a transitional space between the open courtyard and the enclosed space of the ghar. (Fig. 30) These roofed semi-open porches are usually attached to a ghar and face the courtyard, but they may also be attached to the courtyard wall. The baranda is a shaded space used as an extension of the courtyard to support outdoor activities during hot or rainy weather. It also protects assets such as storage urns and animal coops. In more affluent homesteads, the barandas are continuous covered spaces running along the length of the courtyard wall. At times the baranda or part of it may be enclosed to provide additional room for family members.

The Kitchen: Kitchens are small sheds not as well-built as the sleeping rooms. (Fig. 31) The baranda is also often used as a cooking area. The stoves are built in the mud floors of the kitchen. Interestingly, in affluent homesteads with brickwalls and cemented floors, the kitchen or part of the kitchen always has a mud floor with stoves dug into the floor. Usually there are built-in mud stoves in the courtyard for open air cooking during fair weather, which is most of the year. Kitchen utensils include a grinding stone, round-bottomed earthen pots, a winnowing basket and a curved cutting edge fixed to a wooden base.

The Cattleshed: Cattle are kept in cowsheds or the baranda at night. The cowshed is one of the structures surrounding the courtyard. In some of the homesteads, due to crowded conditions, some family members share theirsleeping quarters with their cows.

The Courtyard: The courtyard is the focus and spiritual centre of the home. (Fig. 32) It is swept twice a day and plastered every few days with a mixture of mud and dung. In fact, sweeping the courtyard is the first task to be undertaken each day. In Hindu households the courtyard contains the sacred tulsi-plant and has to be plastered daily and kept meticulously clean; otherwise bad fortune may befall the family.

When women invite other women to visit their home, they will say, "Come to our courtyard." I myself was invited several times in this manner, which seemed symbolic of the status of the courtyard in the home. The courtyard is kept private only from non-kin males. Women, known or unknown, never need permission to enter a courtyard. It is quite acceptable for women to use courtyards to get from one place to another. Men other than family members, however, will never enter a courtyard unless invited. For a male, entering a courtyard without permission is an act of symbolic violation. Even when men close to the family come to visit, they will always call out the name of the householder or make their presence known before entering. Only close male relatives or important male guests are invited to sit in the courtyard. Others are received in the goli.

The courtyard supports all the activities of work and leisure. Cooking, eating, sleeping, child rearing, processing paddy, manufacturing household items (income-generating work for men usually takes place in the goli), sewing and gossiping all take place in the courtyard. Women use the courtyard for the majority of their activities, but mostly sleep indoors even during the hot and humid summers. This is because the courtyards have several entries and thieves may enter. Another reason is that she may be touched by an "evil" wind. The "evil" wind, which mainly affects women, is blamed for many illnesses. In affluent homesteads the courtyard may be plastered with cementand a part of it may be used as a garden. Neighbouring courtyards are usually inter-connected so that women can visit each other without having to go out on the road. The boundaries of the plots are rarely fenced, but the courtyard boundaries are always well defined, even if only with ramshackle straw fences.

The Kanta: The kanta is the backyard of the homestead, which usually contains the vegetable patches, bamboo groves and fruit-trees. (Fig. 33) Often it is a low level area (as soil is dug from here to build the house) with a small water-body and a handpump where women wash their utensils and clothes. Private ponds in the backyards, a common feature in most regions of Bangladesh, are relatively rare in this area. Although the backyard is usually not fenced, it has some privacy because of the vegetation and women feel free to bathe and work there. The kanta is considered primarily women's space.

Sanitation: Of the sixty homesteads surveyed only nine had existing toilets, while two homesteads lost their latrine structures in the flood. The common practice is to use the bushes, cane-fields or mango-groves behind the houses. This practice is the source of complaint for many of the women. As Moinara(30) reported, " Our husbands do not allow us to go to out on the goli, but they do not care if we are seen performing this very private activity. I have heard that a concrete ring and a sanitary slab costs only 70 Taka (about C$2.00), but still they do not see how important this is for us. We have to wait till dark or go before daybreak in order to hide our shame." Her sister-in-law added, "If we have diarrhoea, we are forced to go out in daylight, which is very humiliating." Women who live near canefields are slightly more comfortable as the tall plants afford some privacy. Only nine women reported that they have no complaints about sanitation practices and did not feel shy to go out during daylight. The few homesteads that have sanitarytoilets are of the pit-latrine type, usually placed in the kanta at a safe distance from the house (up to twenty metres). In the landlord's houses the latrines were often placed in separate courtyards. Up to about thirty years ago, there were separate toilets for women in Chowdhurypara.

Urinals, if there are any, are usually located adjacent to the homestead. Urine is considered less polluting than excreta. The reason why the toilets are located at a distance is two-fold. Firstly there is the problem of odour, flies and the sense of pollution. Also, certain members of the spirit world are believed to live on excreta and as such the toilets are often believed to harbour such spirits. This may account for the general reluctance of the rural populace to have fixed toilets. Women are often said to be possessed by spirits when going out to defecate. Women who wait till dark to defecate in the bushes often took their husbands to guard them as this was also the time when spirits were most active.

The village has several old wells, some of which are still in use. Almost all households surveyed, however, depend on handpumps for their consumption needs. These handpumps were either privately owned or government tubewells. Private handpumps, even when shared by several families, were usually installed in the kanta or in the courtyard, while government handpumps were located in the goli. Women bring water from the handpumps in earthenware or brass vessels. They also bathe near them, usually when the menfolk were away at work. If the tubewells are placed next to the road, women carry water home and bathe behind the house. In some households, women bathe in ponds or in the river. There is a special spot in the riverbank where only women bathe.

Also there is a women's pond near Kanapara in Shadashivpur, where women from as far as one kilometer away come for their daily bath and to wash clothes. Although most households have access to handpumps, many women prefer to go to the women's pond, possibly because they can meet women other than their immediate neighbours. There are not many ponds in this area, but the ones that are there, are not used much by women for bathing. Women bathe fully clothed. They often have only two saris, one to bathe in and one to change into. Clothes and utensils are washed at the tubewell. Sometimes they are also washed in the waterbody at the back of the house. (Fig. 34)

5.3.4 Building Process and Rituals

Most homes are built with family labour unless the family is wealthy enough to be able to afford hired help. The building of a new home involves several ceremonial rites. It also involves an established division of labour among men and women when the homes are self-built. (Fig. 35)

Whenever a new home is built, 4 nails are buried in the four corners of the hut, otherwise it is believed that the house will fall in. Women dig the earth from the kanta, bring water and prepare the mud. The walls of the house are built by the men of the family. Women plaster and finish the walls. A roofer, known as gharami is hired to make the roof frame and to cover it with thatch or tiles. Before moving in, a mullah or two madrassa students are called to recite the Quran in the courtyard. People, who can afford it, will have a milad in the goli. A milad is a religious gathering where incidents from the prophets life are discussed and prayers offered collectively. Only males take part in milads. Women listen from inside the courtyard or from behind screened partitions.

For both Hindus and Muslims, the "home is the temple," where prayers and religious rituals are a part of daily life. Hindus have the sacred tulsi-tree in their courtyard and an altar in their huts where they worship their patron gods. Muslims have special prayer-corners in their homes which have to be kept pure and clean. For Muslim women, the home is the only temple. They do not visit mosques.

5.3.5 Examples of Homesteads of Different Socio-economic Groups

House A: Homestead of landless nuclear family (Fig. 36 and 37)

|  |

Jonaki, her husband and three children live in a one-room house with a fenced courtyard in Ajgubi near the river. Her husband is a boatman and ferries people across the river for a nominal fee. They moved to this house three years after their marriage when her affinal home became too crowded. She was fifteen years old at that time. The plot, which is in the middle of a small orchard was given to them by her father who owns the orchard. Jonaki and herhusband jointly built the small house. To ensure privacy, the house has its back towards the street. There is no screen wall in the deori, but a movable reed door conceals the courtyard from passers-by.

The house is isolated and surrounded by big trees. For this reason (so she feels), Jonaki was possessed several times by spirits and had to be exorcised. Jonaki rarely visits her neighbours, but women in groups of two or three come almost daily to visit her. They sit on a string-cot in the kanta under the shade of the mango-trees. The only place that she visits is her natal home, usually by the backlanes under the trees. She has been to Kansat twice. Once her husband took her to attend a huge religious gathering where she sat in a screened enclosure along with other women and listened to the waj - religious discourse. This was, as she noted, a highlight of her otherwise routine life.

Jonaki and her husband had been saving a long time to buy a hand-pump. It stands in a corner of the courtyard surrounded by loose bricks. Previously she used to bring water from the school or from a nearby pond. She and her family use the nearby cane-field for defecation, but she wishes they would have an enclosed toilet as in her natal home.

Jonaki's first child was born in her father's home where she stayed seven months for the occasion. Her oldest daughter is six years old but does not go to school. Jonaki knows how to pray and read the Quran, but her husband never received any kind of education.

Her husband barely earns enough to feed and clothe the family. The reason that her daughter does not go to school is because her only dress is torn. Jonaki tries to supplement the family income by sewing quilts, but she does not get many orders. Her husband and her father would not like her to work outside the home and she too would not feel comfortable. When their situation becomes too desparate her father helps them out. [Fig. 37]

House B: Homestead shared by several landless families (Fig. 38 and 39)

|  |

Mukta is a fourteen year-old orphan, who along with her two younger siblings, lives in the homestead of her paternal uncles. The homestead is entered through a passage between two huts. On the left of the entrance is her parental homestead, while on the right is the homestead of her father's cousins. Both homesteads are open towards the kanta which slopes down into a muddy water-logged space. The nuclear families who share the homestead all have separate cooking spaces.

Mukta's uncles are too poor to support her, so Mukta works in one of the landlord's houses. Every morning, she walks three kilometers to her work-place using the foot-paths through the orchards because "I don't like walking in front of men sitting in the goli and I can walk in the shade of the mango-trees." Mukta works a long ten-hour day. Her employer depends on her to help in the housework, as well as "outside" work such as getting wheat milled at the mill. As wages, she gets food for herself and her siblings and clothes twice a year. She also receives the yearly zakat (compulsory charity according to Islamic rules) from her employer's family.

In the homestead, each conjugal family shares a room. Mukta's youngest uncle, who recently got married, built a small straw hut in the courtyard for himself and his new wife. At the time of the survey, his wife was visiting her natal home. Her father refused to send her back till a proper mud-hut is built for her. Mukta and her siblings do not have a hut; her parents' hut whichrightfully belongs to them, was occupied by one of her uncles. Her father's cousins allow the three children sleep in a sheltered baranda in their homestead. There, among the storage urns, Mukta has set up her little household. A part of the long baranda was enclosed with bamboo matting to prepare a birth-room. One of the daughters of the house, who has come to her parent's home to give birth to her first child would live there for at least six months. Mukta hopes that when her cousin returns to her husband, she will be allowed to use the small room for her family.

House C: Homestead of a farmer (Fig. 40 and 41)

|  |

Jahanara is the middle-aged wife of a subsistence farmer. By Bangladeshi standards they are comfortably well off. They own seven acres of land and two cows. She has eight children (she is embarrassed at the large number) - oneson and one daughter are married. Her daughter-in-law is twelve years old and has come on a visit (she will live in her natal home for another two years). Jahanara sometimes brings her on visits "so that she will learn to love us." She is careful not to let her son alone with the girl as she is still young. In the crowded two-room house this is not difficult.

The house is about twenty yers old. It has a walled courtyard with a continuous baranda running along the wall. The entrance through the corner of the courtyard is fitted with a door that can be locked.

Jahanara's days are filled with numerous household chores, which she does with the help of her two daughters. She does not do any gainful work because as she says "while my husband is alive, why should I work?" Jahanara rarely visits her natal home as she is too busy to leave her household for longer periods. She remembers the thrashing she received from her husband when she once went to her natal home without his permission. Nowadays, she visits freely in the neighbourhood. Her age has afforded her mobility and she likes to joke with the neighbours - even the men. However, her movements are restricted to her neighbourhood.

House D: Homestead of a landlord (Fig. 42 and 43)

This large two-storey brick house built fifty years ago is in the middle of the landlord's enclave. Two brothers and their families used to share the house, but one brother built a new house nearby and moved there two years ago. At present only their mother, her older son and her daughter-in-law live in the huge house. The grand-children are all grown up and work or study in towns.

The main entrance door of the homestead is hidden behind a screen wall. The house has three courtyards - one for male guests, the main central courtyard and a service courtyard in the kanta. The central courtyard again is divided into two spaces, a cemented portion for drying produce or fuel and other household tasks and a separate fenced portion adjoining the kitchen for washing and cleaning. The handpump and a small vegetable garden is situated in this part of the courtyard. In contrast to houses in the rest of the village, houses in Chowdhurypara have fairly large windows, which however are hidden from the street by high walls.

Saleha Chowdhury, the grandmother, remembers the times when women were strictly confined to their homes in Chowdhurypara and never went out except in a covered palanquin. Every family had special decorated oxcart covers to be used by the women while travelling. Girls received instruction at home in Persian and Arabic, as well as Bengali. Her daughter-in-law studied in a Calcutta school. Two of her grand-daughters are graduates and the rest are in school.

Saleha and her daughter-in-law have two maids to help take care of the house. Their dafadar (field supervisor) also helps in household tasks whenever necessary. The two women hardly go out, except for extended trips to town to visit relatives. While in Chowdhurypara, they are totally dependent on theirmaids to take care of outside work. Their situation shows how the seclusion of one class of women is dependent on the mobility of another class.

[ TopOfPage(); ]5.4 Women's separate world: Gender roles and space use

5.4.1 Separate Roles

From a very young age, boys and girls from the villages are introduced to their separate roles in society. Boys are given preference in matter of nutrition, education and childhood demands. They have more time to play and to explore their surroundings, while girls, from a very early age are expected to help with household work, to collect fuel and to look after younger siblings. By the age of eight or nine, depending on the economic status of the family, most girls are quite adept in housework and rearing children. Boys, on the other hand, are sent on errands or to fish in the roadside ditches. They are gradually separated from the females of the household and taught the skills of ploughing, sowing, reaping and selling the crops in the market, which are considered male activities. Girls learn the processing of produce - work that can be done at home. From early childhood, both girls and boys internalize their different roles in society and their separate spaces -the private spaces in and around the house for girls and the more public spaces in the village for boys.

5.4.2 Purdah Practices

Purdah practices in the study area are not as strict as in some other regions of Bangladesh. Women are more relaxed about conversing with non-kin males, although only when necessary. None of the women interviewed own or wear a veil (wearing a veil is more of an urban phenomenon) but they modestly cover their heads with the end of their sari in the presence of adult males. When going out of the homestead, they can often be observed holding the end of the sari with their teeth, thus obscuring the lower part of the face. (Fig. 44)

At what age a girl should be confined to the homestead depends more on her physical appearance, than her age. A girl who looks mature at twelve would be confined earlier than a girl who still looks like a child at fourteen. A girl who is considered to be old enough to be confined, is expected to do a major share of the housework, including fetching water or fuel. A new bride, however, who may be the same age as an unmarried girl in the family, observes purdah more rigorously and is not even allowed to visit neighbours. At the Adult School for women, I found three women from the same household, but their newly married brother's wife did not accompany them. "She is a new bride. It would be shameful for the family if she goes out," they explained. As a woman grows older, she gradually gains more freedom, both in mobility and in her relations with men. An older woman reported that she took over tasks that involve going out of the homestead (like taking goats out to graze or to collect fuel) to ensure strict purdah for her daughter-in-law.

The observance of purdah seemed to me a complex practice with many subtle shades of behaviour and often contradictory patterns. For example it was quite acceptable for me to use the D.B. road during my field work, except on hat (weekly market) days. Walking about on those days, when there was a lot of traffic on the road, was considered bepurdah (non-purdah). So apparently purdah depended not only on the presence of males, but on the number of males that were present. Similarly, women use the back-lanes not because they will not meet any men at all, but because they will meet fewer men there. Also the social status of the males dictated whether the woman should cover her head or not. If a known male visitor is a social inferior or much younger than the woman of the household, she will not bother to pull her sari over her head. If however, the visitor is a social equal, an honoured guest or a relative by marriage, e.g., daughter's father-in-law, women cover themselves immediately and retire from their presence.

Most respondents considered purdah to be an ideal practice to which they aspire. It symbolizes for them a comfortable and sheltered life. It also raises the status of the family and brings honour to the family name. A woman who worked as a domestic servant would not let her teen-age daughter take up similar employment, although the family was barely able to sustain itself. She felt it might hamper her chances to contract a good marriage.

One of the first acts of upwardly mobile families is to confine the womenfolk within the homestead. A middle farmer, who became rich through smuggling, built a closed toilet for his daughters-in-law. He also forbade them to visit in the neighbourhood, which they had been accustomed to do previously. To emphasize the separation of sexes, all the new brick-built houses in the villages have proper baithak-rooms with separate entrances, while in the older mudhouses this feature was often missing.

The social order in a village, which includes adherence to purdah, is regulated by a very strong gossip network. There are no secrets in a village. Unbecoming behaviour of a woman can be cause for loss of face or social ostracisation of the family concerned. A woman's behaviour is so controlled by social mores that the norms of purdah are internalized by women and practised as correct behaviour. For example, in a group discussion, most women agreed that if a woman leaves the immediate neighbourhood without her husband's permission, it can be valid reason for wife-beating.

5.4.3 Purdah and Status

Status is also another determining factor of what constitutes purdah behaviour. For example, the landlords' wives do not think it necessary to hang curtains while travelling by oxcart, while women of other classes would not travel otherwise. On the other hand, upper class women feel it is extremely non-purdah to go out of the homestead for natural functions, while for women with lower status it is a common practice.

Purdah in Chowdhurypara is relatively relaxed. Women freely visit each otherin the afternoons and use the D.B. road to visit the other members of the family who do not live in Chowdhurypara. However, even they avoid the D.B.road when hats are in session. For trips ouside the village, women will use oxcarts to travel even if the trip is within walking distance. It is considered a loss of status and purdah to walk longer distances. The girls, when they reach puberty are not confined to their homes. They freely roam about the neighbourhood and congregate in the evenings to walk and converse. Three fourteen year-old girls are well-known for their tom-boyish exploits like climbing trees, fishing in the ditch and playing pranks. This kind of behaviour, which would not be tolerated in the other paras, is looked upon quite fondly by their families. Nevertheless, the young girls do not move out of their own neighbourhood unless they are travelling to town escorted by male members of the family. The principal of the girl's school, a landlord's wife, who is also the head of several charitable organisations in the area has to move about alone quite often. Although villagers appreciate her work, her behaviour is criticized by mullahs and other men of the village, often to her face. Another landlord's wife does not depend on male members of family for work she can do herself. She goes to houses nearby to buy eggs or milk. On one occasion, when her husband was absent, she even went to the orchard to supervise pruning of their trees. She is however an exception. The reason that the women of the landlords' family are more relaxed about purdah restrictions is that their status is quite secure in the village. They obviously do not feel the need to observe purdah for men who are their social inferiors. Nevertheless, their movements too are restricted to some extent.

Thus, while due to education and exposure to urban life, the women of the landlords' families were giving up many trappings of purdah bahaviour, lower class families were seeking to emulate the status that strict purdah signifies, not by emulating the present behaviour of the upper class women, but by what was once the tradition prevalent in Chowdhurypara. Among the farmer class, strict seclusion is still the ideal.

The "status" of a space or a facility is also an important determinant whether it is acceptable for women to use it. For example, neighbouring Kansat has weekly and daily temporary markets selling daily necessities, where women arenoticably absent. On the other hand, the permanent market at Kansat, with well-built shops selling clothes, books and other consumer items is an acceptable place for a woman to visit, escorted by a male member of her family.

5.4.4 Women and Folk Religion

Folk religion also has a strong influence on the mobility and movement of women and their use of local spaces. The rural syncretic belief includes the belief in an active spirit world which is largely associated with women. When a village girl reaches puberty, many sections of the village become off-limits for her due to the belief of evil spirits lurking in different spaces. If she is menstruating, she will never venture near big trees or leave the home after dark, as she may be harmed or possessed by evil spirits in her polluted state. In Bajitpur there are two places in the village which are specially dangerous - a swampy waterbody and a group of graves in the middle of the village. Women will make wide detours to avoid these spaces. A pregnant woman is not allowed to leave the homestead on full moon days and eclipses, for fear of bearing a deformed child. Similarly, a new mother and her baby are also believed to be specially vulnerable to spirits and are not allowed to leave the homestead for forty days. Spirit possession is a fairly common occurence among the village women. Any behaviour deemed abnormal is ascribed to possession by spirits. Excorcisms by local ojhas (excorcists) are held in the courtyard and involve incantations, fires and flowers and often merciless beatings of the women involved. Usually homesteads are supposed to be safe, but at times, the entire homestead is considered to be possessed. Insuch cases, the mullah is summoned to give azaan (call for prayer) in the four corners of the house to "close" the house to entry by evil spirits.

Women are excluded from mosques, but often they are regular visitors to saints' tombs and shrines, a common fixture in the countryside. Both Hindu and Muslim women visit these shrines to pray for a special favour, such as a son. The tomb of Sheikh Niyamatullah, a sixteenth century saint, is about eight miles from Bajitpur. Several women reported visiting the shrine for prayer.

5.4.5 Women's Work

Women spend most of their time in domestic work, which is labour-intensive and time-consuming. (Fig. 45) Women use spaces in around their homesteads for their daily activities. (See Appendix 2) Flour and spices have to be ground by hand. Paddy has to be husked manually to make rice. The homestead has to be swept twice daily and plastered periodically. Repairing and replastering the mud house is also a woman's job. Cooking is done on mudstoves with leaves and sticks for fuel. Cooking utensils become covered with soot and have to be cleaned by rubbing them with ash and coconut husk. Cattle is usually taken care of by men, as they are tied in the goli, but women take care of goats, chicken and ducks. However, women collect dung to make dung-sticks for fuel. If there is a vegetable patch in the kanta, it is within the women's domain. Vegetables grown commercially on the field, however, is grown by men. Women pump water from the hand-pump and carry it inside the homestead. Quilts, pickles and mud storage bins are made in the afternoon, during leisure time. This is also the time when women visit each other, pick lice and put oil in each other's hair.

Women spend a considerable time in productive work in the agricultural sector. Women work daily in processing and storing the farm produce. Men grow paddy, but women are responsible for paddy processing, storage and seed germination, in short, all the activities that can take place within the home. (Fig. 46) Paddy-boiling and drying is done in the courtyard. If there is not enough space this activity sometimes spills out to the goli. This is considered tobe purely women's work. One respondent described the uncommon devotion of a husband by stating that "he even processed paddy when his wife was ill." Fields are totally off bounds for a woman unless she is walking through them to travel. No woman has ever been known to work on the fields, even during periods of great want. Also women do not go to the fields to deliver food to their menfolk. The men usually carry their meals with them or it is delivered by children.

5.4.6 Women's Gainful Employment

There are very few opportunities for women to work for wages. They are absent from the main agricultural businesses of mango and sugarcane. Sugarcane growing and marketing is totally in the male domain. Sugarcane is grown on the fields and marketed from the fields. If molasses are made they are also made on the fields in big vats. Only men are involved in growing mangoes and caring for the orchard. Mangoes are also marketed from the orchard itself. Women are only involved in making amta, a dry sweet made from the juice of overripe mangoes or mango-pickles made with green mangoes collected from the ground after a storm. These are usually made for home consumption in richer households and for sale to wholesalers in poorer ones. Poor women often process paddy for wages. Paddy is brought from richer households, which the women husk at home or get husked at the ricemill. The paddy is either delivered to them or male family members or children bring it home. Only three of the women interviewed stated that they themselves went to the richer households to process paddy there or to bring it home. All of them were middle-aged widows. The electric ricemill, although viewed by the villagers as a symbol of development for the village, was actually detrimental to theincome-earning capacity of the women. Husking rice manually by the dheki is a labourious and backbreaking task, but the advent of the ricemill meant that many of the richer households could get their rice husked at the mill at a lower price. Thus opportunities for work, which are normally limited, decreased even more. Parboiling and drying is still done at home and the rice is husked at the mill. Another upshot of this development is that as very few women are able to go to the ricemill, which is next to the D.B. road, they have to be dependent on their husbands or their children to get the rice husked. Some of the families, if they manage to save or borrow some capital, buy paddy and husk it for profit.

Another traditional way for women to earn is by sewing quilts known as katha. These are hand-sewn and often beautifully embroidered. The kathas sewn in these villages are made for local consumption.

Domestic work in richer households is another way for women to earn a living. Usually such work is not remunerated in cash, but by meals for the worker's family and clothes once or twice a year. Respondents stated that, not so long ago, no married woman, however poor, would engage in domestic work, as it reflected on the honour of the husband. Nowadays, poverty has driven married women to hire out as domestic help, but the majority are unmarried young girls, or female head of households.

The government employs poor men and women in the "Food for Work" (FFW) program, in which wheat is given in exchange for cutting earth to repair roads. In Shampur Union there is only one gang of women earth-cutters consisting of fifteen women. In a population of women of which the majority are in need of gainful work, the small number of women employed in this kind of work represents the low status and loss of purdah that it entails. All fifteen women thus employed are widows or divorcees whose families are totally dependent on their income. Two of the women are from Bajitpur. I met one of them - Sabina, in her mid-thirties. After her husband died she tried very hard to support her children by the traditional income-generating work such as processing paddy and sewing quilts, but they often went hungry. She finally decided to join the FFW program, as it meant regular employment. At first herbrothers-in-law objected to the loss of purdah that this meant for the family, but they were too poor themselves to support her and eventually agreed. (As she was living on their property she had to obtain their approval.) Her neighbours also spoke ill of her and predicted that no-one would marry her daughters. But the fact that she worked in an all-female gang and that her demeanour and dress remained as modest as before made her work acceptable to her neighbours. She is now commended as she did not ask for charity to support her children but relied on her own labour. Nevertheless, although there are several other destitute women in her village, only one of her neighbours followed her example. To leave the confines of the bari and to work on the road, a "male" space, obviously is a bold step that not all women are willing or able to take.

5.4.7 Access to Social and Economic Institutions

Women are excluded from most village institutions. The "publicness" of these institutions discourage women from taking advantage of their services.

Legal Services

Women are often denied their Islamic and constitutional rights, but are powerless to fight for them because of the negative and public image of legal institutions. Respondents reported that women who attend court are a source of shame and loss of face for their families. None of the respondents had ever attended court. Most of them had given up their right to their parental property in favour of their brothers, so that their brothers would notconsider them a burden on their naior (vacation at parental home) visits or if they are forced to return to the parental home. In the village shalish (traditional arbitration court), which are called on to mediate village disputes, women are almost always represented by their male kin - husband, father, brother or adult son. These courts, which are held in the baithak and goli of the matbor (faction chief) or the neighbourhood mosque are all-male affairs. Only older widows have at times requested arbitration and attended these courts.

Marketing

Although women are excluded from daily and weekly markets, both as vendors and buyers, they are not totally excluded from commercial activitites. Door-to-door vending is very common. Most women do not observe purdah in front of male vendors, as mostly they are considered village "brothers." Pots and pans, cooking oil, bangles and ribbons, vegetables, fish, etc. are some of the items that are sold door-to-door. Transactions usually take place in the courtyard, where neighbouring women also congregate to sample the wares. (Fig. 47)

There is only one woman vendor in the area and she is a Hindu. This activity is not acceptable to Muslim women, however poor they may be. Wholesalers also visit the homesteads to buy eggs, milk and home-grown vegetables from the women. The money earned from selling these products remains in the hands of women. In poor households this money is obviously spent for food and other household expenses, but if possible it is spent on a few luxuries like plastic bangles or ribbons for the children.

There are small neighbourhood shops in all the villages selling daily necessities. These road-side shops are meeting places for males in the afternoons. Women go to these shops only when they have no alternative, for example if no-one else is at home. One husband reported that his wife never visited the neighbourhood shop, although it was a few yards from his doorstep. The wife, however, later told me privately that she does visit the shop ifnecessary, but only when her husband was out.

Credit Facilities

Professional moneylenders known as mahajans are usually a common feature of rural life, but there are no professional moneylenders in these two villages. For small amounts of credit villagers are mainly dependant on richer relatives or friends. Faction chiefs often advance personal consumption loans to members of their communities. An agricultural bank located in Bajitpur advances loans to cultivators. Women are dependent on other women for small loans, which they use to buy a few chickens or ducks, or to buy paddy for processing. No woman ever visited the Agricultural Bank or was given a loan.

Grameen Bank, a mobile bank which gives income generating loans mainly to poor landless women, has started operations in one of the paras (Ajgubi). Grameen Bank recognizes the limited mobility of rural women and sets up weekly office in one of the courtyards/barandas of their members. Other members gather there and make their weekly loan repayment and compulsory savings contributions. (Fig. 48)

One of the loan recipients, Amena Begum, the only earning member in a family of five, borrowed Tk 2000.00 (approx. C$57.00) and bought two goats, some ducks and some paddy to husk. She repays the loan at Tk40.00 (C$1.20) per week for fiftytwo weeks. With her nominal salary as the school cleaner and the money she is earning from paddy-husking, she manages to support her family. She described how access to a small loan helped her to care for her family on a daily basis and to raise their standard of living. They were now able to have two meals a day instead of one.

Healthcare

Women in this area have little access to healthcare facilities. The usual practice is for husbands to describe the symptoms of their wives' illness to the male doctor in Kansat or to the two homeopaths in Bajitpur and bring medicine for their wives. Unless it is absolutely necessary women are nottaken to the doctor. This is both for reasons of purdah, lack of mobility and the inconvenience of going to the clinic. Women's lack of mobility and the long distance that has to be covered through muddy roads to reach government health facilities in Kansat means that women are mostly left out of modern health services. They are thus compelled to rely on indigenous health care practices which they can avail of easily and which operate within the given social constraints imposed on them. There are several village practicioners, known as the kobiraj, who dispense traditional herbal medicine. There are also several women kobiraj in the area, who are quite popular for treating women.

The only health-visitors that reach the women are the two female family planning workers who distribute contraceptives and advice women about planning their families. They visit weekly in different paras, setting up "shop" in some of the courtyards. Neighbourhood women, who are interested in availing of their services, or out of plain curiosity, gather in the courtyard.

Education

There are two primary schools, a girls school and a coeducational high school in this area. There are also two adult education centres in Shadashivpur run by an NGO named Sha-unnayan. All the schools for children are situated on land donated by the landlord family. One of the primary schools was established in 1882 by them. In this school there are 372 students of whom 169 are girls. The Government High School has 304 students, of which 131 are girls. The number of girls attending school is steadily increasing. This is probably as much due to changes in attitutde towards female education as to the presence of several educational institutions in the area. A school within a short distance becomes an important consideration for attendance, specially for girls approaching purdah age.

All parents interviewed agreed that education for children, both boys and girls, is necessary, but few sent their children to school beyond the age of ten. The drop in attendance is most acute in Grade Five. The dropout rate among girls is higher than for boys, the main reason being early marriage or confinement to the home at onset of puberty.

Both girls and boys are needed at home to help in household work, childcare and running errands. Because the mothers' mobility is severely restricted, children have to do most of the work that has to be done outside the homestead, such as taking animals to graze, collecting fuel and fodder, taking food to the fields, going to the neighbourhood shop, etc. In fact, the mothers' adherence to purdah is dependant to a great extent on the children's mobility. This fact is not taken into consideration in school timing. Schools open in the mornings when the children are mostly needed at home. The all-girl school in Binpara has helped in ensuring that more girls stay in school longer than usual. Parents feel more comfortable in sending girls to a school where they will not come in contact with young boys. Nevertheless, girls do drop out at an alarming rate; but if a girl is specially promising, teachers will visit her house in order to try to convince her parents to keep her in school. In the government high school, boy and girl students attend the same classes, but sit separately in the classroom. During break the boys play or congregate on the playing field, while the girls gather under the trees near the teacher's staffroom. Although the school is coeducational, the children are totally segregated by sex, both in and outside the classroom, and are not encouraged to communicate. There are no female teachers in this school. Parents however do not stress the need for female teachers; male teachers are quite acceptable because of their special status as educationists. For the same reason parents do not hesitate to send girls to religious schools known as maktabs in which all the teachers are male. Often, a religious education is the only education deemed necessary for girls. Among the mothers, the majority only received a religious education, i.e., they can read the Quran in Arabic, know how to pray (all Muslims pray in Arabic) and have some knowledge about Islamic history. In well-to-do families children do not go to the maktab, but receive religious education at home from private tutors.

There is an Adult Education program run by an NGO active in this region. Classes for women are held in a courtyard in a farmer's house, while the male school is held in the goli of another homestead. There are about twenty-five women in the class. The course that they follow is known as "functional education" and lasts for six months. It teaches them the rudiments of reading, writing and arithmetic and educates them in healthcare, nutrition, etc.

Classes are held at four o'clock in the afternoon when the women are not so busy with their domestic work. The students ranged in ages from sixteen to fortyfive. The teacher, who is a matriculate of the same para, reported that there have been no drop-outs and there was already a waiting list of women who wanted to attend the next course. All of the women were, however, from the same part of the para. Distance seems to be a determining factor in the attendance of school. (Fig. 49)

5.4.8 Women's Social Networks

Men and women have separate and parallel networks which they depend on for emotional, social and economic requirements, but for women's social network, the boundaries of the para are more relevant than that of the village.

Women, in their social behaviour, seem to be less conscious of class differences than men. I met long-time maids in Chowdhurypara, who have become close friends and confidantes of their female employers and are frequently consulted on family matters. Women of different classes form relationships that are mutually beneficial. For example, a poor woman will help out in a richer neighbour's house (not as a servant) when needed. This will ensure that she occasionally receives charity or a small loan from the neighbour.

Respondents spoke of the existence of a women's network of loan relationships, which is largely hidden from men. Some women save small amounts of money in order to lend it at interest to other women. The interest rates vary from five to twenty percent, depending on the relationship between the borrower and the lender.

While the male villagers depend on the shalish or the elected Union Chairman's for arbitration, women more often rely on his wife to do the same. The Chairman's court is held in the covered porch of his baithak, while that of his wife is mobile - she usually arbitrates in homesteads that she visits in the course of her work.

Women depend on other women for taking care of children and the household when they are ill. During deaths, it is the duty of women to visit the household to help and condole - men usually only attend funeral prayers. After births and marriages, women pay social visits to "see" (with a small gift) the new baby or the new bride. There are series of rituals in the woman's domain, dealt only by women.

Women visit neighbours' courtyards almost daily. This frequent interaction with other women helps to decrease the tedium of a confined life and keeps their social network active. Women depend on this network for gathering and disseminating information. Children often act as messengers. The beggar woman who moves from house to house to beg and to chat is also a part of the information system. (Fig. 50) For example, when Amena from Shadashivpur, came to our house on a Friday (the Islamic holy day, when people give alms), we came to know that House B was having koi-fish for lunch, that the couple in House F had quarreled and the wife had gone home to her parents and that House J had visitors from town.

5.4.9 Lifecycle Rituals

The different spaces in the home play an important part in marking the lifecycle rituals of the family. Except for the Islamic rites, men are usually excluded from lifecycle rituals such as birth and weddings; these are part of the women's domain.

Birth

None of the women interviewed ever went to a clinic or hospital to give birth. The usual practice is to go to the natal home for childbirth, at least for the first child. This practice is followed even in poor households. Only a few women reported that their natal families were too poor to support them during childbirth. For the birth a room or part of the room is set aside for the purpose and for forty days after the birth it will be known as the atur ghar or birth-room. Usually the child is born in the presence of female relatives or neighbours and a midwife is only called to cut the umbilical cord. There are no midwives in the Bajitpur and as the midwife is fetched only after childbirth, the cord is often cut only an hour or two after childbirth. Midwifery is considered to be a low status and polluting occupation and there are no Muslim dais (midwife) in this area. The usual practice is to give birth by squatting on the floor and the baby is mostly caught by the mother herself as this act is considered highly polluting. After the birth, the placenta is placed in an earthen pot and buried in the kanta. Women from richer households can afford to have a midwife throughout labour and also for days afterward to massage both her and the baby. Some women deliver babies themselves, as they are too poor to afford the services of a midwife. One woman with six children reported cutting the umbilical cord herself with a blade or a sickle (dao).

After child-birth, the mother and the new-born stay strictly confined to the birth-room for seven to nine days, during which the mother is supposed to do nothing except look after the baby. One respondent reported that for the birth of her sons she was confined for seven days and for her daughters for nine days, as girls are considered to be more polluting. For the period of confinement, a fire is kept burning constantly in the often windowless pitch-dark room, filling it with smoke. This fire is a safeguard against spirits harmful to babies. The only time the new mother leaves the room is when she goes out for natural functions. As in her post-birth state she is considered to be most vulnerable to possession by spirits, which in turn could harm the child, she is always accompanied by another female and carries a small sickle and a burning dung stick in her hand. These are meant to protect her from harm. Even after confinement is over, for upto six months, whenever she leaves the homestead with her child, she carries something made of iron to ward off evil spirits. After the nine-day period, she has a ritual bath and the birthroom is swept and plastered, the bed-linen is boiled to purify it and the new mother may now use the other spaces in the homestead. She is considered totally free from pollution only when forty days have elapsed. At that time both she and the birthroom are again ritually cleansed and she rejoins the normal activities of the household. During those forty days, many neighbouring women will not visit the household as the homestead is considered to be polluted as well.

Marriage

Weddings usually take place in the bride's home. Pre-wedding ceremonies give women a chance to sing and dance in the courtyard, while men are careful to stay away. Often a baithak is first built to receive a new bride-groom and his party on the wedding day. In a poor household, the groom had to sit under a tree in the goli in the absence of a proper baithak. A maulvi and twowitnesses first ask the groom's consent, then are escorted into the homestead to hear the bride's consent. Marriage prayers are held in the goli among the men. Only after the marriage has been solemnized is the groom taken into the courtyard to sit next to his bride. Some wedding rituals are then carried out by the women, before the bride leaves with her husband. The incorporation of the bride into her husband's family is marked with a ritualized entrance into her husband's home. There will be some special rituals in the deori of her affinal home, again carried out by the women of the family, to welcome her into the family and to make her entry into the homestead auspicious. This may take the form of reading a passage from the Holy Quran or more elaborate celebrations.

Death

After a family member dies, the body has to be washed and wrapped in a shroud according to Islamic injunctions. This usually takes place in the courtyard. For a female, a portion of the courtyard is screened off, while women wash her body. Water is collected in a hole dug in the courtyard. Funeral prayers are held in the goli, mosque or graveyard. A woman's corpse, while being carried on a byre is usually covered with an extra cloth or an oxcart cover to signify purdah. At times, the body is buried within the homestead - in the kanta or the goli. Women do not take part in burial prayers or the burial itself. Women also do not visit graves or graveyards. Their presence is considered to be polluting to the sacred ground.

5.4.10 Women's Cognition of their Surroundings

The usual tool for evaluating awareness and perception of spaces is by having the subjects draw cognitive maps. Due to the limited and often non-existent literacy of the respondents, this medium could not be utilised. Rather a series of questions attempted to draw out women's knowledge of their surroundings. From interviews, it was evident that women from all groups lacked adequate knowledge of their environment. Often they only knew the name of their own para. A few women could name some other paras in the village but could not point out the directions. They were also vague about landmarks and public institutions. Their world seemed to be confined to their own para andthose that they visited, which were very few. Even poor women, who were relatively more mobile, only knew the way to their places of work. One of the questions I would ask during interviews was, " Could you give me the directions to such and such place in the village?" Very few women could answer such a question accurately. Evidently, even as children, the respondents had not explored their surroundings to a great extent.

[ TopOfPage(); ]5.5 Poverty and space use

The economic condition of a family determines how strictly its female members can observe purdah. Poverty forces women to work outside the confines of the home. Poor women mainly seek employment from other women in wealthier households, either as domestic help or as processors of produce. In Bajitpur and Shadashivpur, there were few other opportunities for women to make a living.

The only women observed walking on the roads alone were poor women going to work or to bring work home. Women beggars also go about alone. Begging door-to-door is considered to be very non-purdah. There is only one woman beggar in Shadashivpur, who is an old widow supporting a divorced daughter and two grandchildren with her earnings. Every Friday, however, several younger women from another village come to beg in Bajitpur and Shadashivpur. They are looked down upon by the villagers and do not receive much sympathy. These women, along with domestic workers, are often victims of sexual exploitation as they are not considered as respectable as women who observe purdah.

Respondents informed me that before the famine of 1975, very few women left the house to earn a living and women were rarely visible on the village roads. Disaster conditions, natural and man-made, together with landlessness and lack of work opportunities have brought increasing impoverishment to this region. Also the rise of female heads of household has significantly increased (the national figures are 15%), indicating a breakdown of traditions. In better times, these women and their families would have been the responsibility of male kin. As families become poorer and the traditional extended familystructure disintegrates, such support is often not offered. Women who have been conditioned to be dependendent on male members of their family often face what Chen calls a "frightening financial independence."

In better times, these women were sustained by the rural economy. But in the present economic climate, even women with male support have to find ways to supplement the family income. This does not mean, however, that women are willing or able to do "outside" work, which is not acceptable to the community. Not many women opted to work for the "Food for Work" Programme, as it involved working on the roads and crossing into "male" space.