The case study analyzes the existing sanitation in the coastal communities of Puerto Princesa, in order to determine essential factors for the provision of sanitation systems for the community. This chapter discusses the range of problems encountered by the community due to absence of sanitary means of disposing human wastes. Other sanitation and environmental issues are considered accordingly to give a clearer picture of the problems. The study is based on the results of the field survey and research conducted by the author in June 1993.

5.1 Basis of Analysis

In analyzing the sanitation conditions in the coastal communities, an understanding of the community layout and housing conditions is necessary. These factors have a direct bearing on the sanitation conditions in the community and the problems related to them. The following discussions illustrate the typical community layout and the varying conditions among the households depending on the location of their houses within the coastal site.

a. Community Layout

A typical layout of the coastal communities is a comb-like structure, wherein an access road or pathway, acting as the base of the comb, runs along the coast. From this pathway or road, main wooden walkways supported by stilts branch off, extending towards the bay. These major wooden walkways give access to the different houses.

The two communities studied in detail illustrate this layout. In the case of Barangay Matahimik, the community is divided into five zones. Zones are identified through the major walkways that branch off the mainland, extending to the waters. The main access to the community is through the small street, called Calle Bajo, found at the west end. A long concrete pathway running along the southeast perimeter of the community is accessible from this street. From this pathway, wooden walkways on stilts branch-off, giving access to as many as 12 houses at one side which are at least 120 meters long. In the case of Barangay Pagkakaisa, the main access is through a coastal road, called Reynoso Street, which is the northeast perimeter of the community. From this road, six main footpaths branch off, providing access to the houses built above the tidal mudflat and the water. The layouts of the two communities are illustrated in Figures 5.1 and 5.2.

b. Housing Conditions

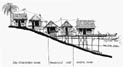

An actual count of houses in the community conducted by the city government of Puerto Princesa last May 1992, shows that there are 2,367 houses built in the community. Conditions vary among the households depending on the location of their houses within the coastal site. To illustrate these varying conditions, three zones, consisting of the dry, transition and water zones are defined.

The dry zone includes houses occupying the innermost strip of the coast that is relatively elevated and is not reached by the water even at high tide. Though this area is characterized by high ground water level, the level varies depending on the exact location of the house. The transition zone is between the elevated and water zones. This includes houses built above the tidal mudflat, the site of which is submerged in water at high tide and is dry at low tide. Finally, the water zone is the outermost strip of the community, with houses built above the bay itself. A house at the outermost edge of the water zone can be as far as 200 meters from the main stable land.

There is no exact boundary among these zones, since it is very difficult to define precisely the high and low tide levels of the bay. These zones were defined to represent the varying conditions within the community and are used as a basis of analysis throughout the thesis. A graphical representation of the zones is shown in Figure 5.3.

Housing conditions vary in terms of building materials used. From the visual survey of the communities, it was observed that some of the houses located on the dry and elevated regions are built with stronger materials such as concrete hollow blocks for walls, concrete flooring and foundation.

On the other hand, houses built on the transition and water regions are made of lighter materials such as bamboo, mangrove and palm leaves. As shown in Figure 5.4, the houses in these areas are supported by stilts. Their floor level is at least a meter from the highest level of water.

[ TopOfPage(); ]

5.2 Existing Environmental Sanitation

The analysis of the environmental sanitation in the coastal communities includes human waste disposal, the available water supply service levels, wastewater and solid waste disposal. Some existing services such communal toilets, water supply and garbage collection were provided by the local government to upgrade the sanitation conditions within the communities. Other aspects such as health related problems as well as the impact on the environment are discussed accordingly.

a. Human Waste Disposal

Existing sanitation facilities in the community are categorized as either communal toilet facilities provided by the local government and private toilets built by the people themselves. Though, these facilities are available, they do not guarantee the safe disposal of the excreta. Problems associated with the existing sanitation facilities are discussed below.

The communal toilets provided by the local government in the coastal communities were located on the elevated areas to simplify the provision of waste treatment facilites. In the case of Barangay Pagkakaisa, as shown in Figure 5.5, the communal toilet is located between zones 4 and 5. The facility has six stalls with a communal septic tank for waste treatment. At present, it is being used and maintained by six households who live close to the facility. It is not made accessible to the other community members at all.

An interview with the community head of Barangay Pagkakaisa indicated that in the past, usage of the facility was a failure because the people did not know how to maintain it and it earned a reputation as an unsafe place, especially for children and women. Because of this, it was closed for some time. The residents living near the toilet, expressing their need for the facility, started to informally maintain it until it became their personal facility. At present, the six families who have access to the facility hold the key to their respective cubicle.

In the case, of Barangay Matahimik, the communal tolet is located along Calle Bajo at the southwest side of the community. The house at the opposite end is approximately 400 meters from the facility. The built toilet has six cubicles with a septic tank for waste treatment. As in the case of Barangay Pagkakaisa, improper use and poor maintenance were the problems. Most often stones were found inside the toilet seats. At present, the facility is locked and is not available to the community.

The unsuccessful attempt to provide communal toilets resulted in people providing their facilities. In Barangay Matahimik, 22 out of 26 respondents have private toilets, while the rest use their neighbor's toilet. In Barangay Pagkakaisa, all households interviewed have individual toilets. While toilets may be available in most households, no sanitary means of disposing human waste exists. In Barangay Matahimik, only one of the respondents with private toilets has a septic tank for waste treatment. In Barangay Pagkakaisa, only two respondent have septic tanks. The individual toilets of the rest are simply makeshift overhung toilets with human waste directly disposed into the bay. A detailed description of these toilets is discussed below.

Private toilets are built inside the houses, or outside, as extensions or as separate structures. The type of toilet built and used by the people varies depending on the location of the house. For some households built on dry and elevated areas, pour flush toilets were installed with septic tanks for on-site treatment.(1) Household no. 233 of Barangay Pagkakaisa, located within the elevated site, was able to build a pour-flush toilet with a septic tank underneath. Figure 5.6 illustrates this case.

Although households located on drier and elevated areas can have septic tanks for waste treatment, this does not guarantee sanitary means of disposing waste. Problems of effluent disposal from septic tanks may occur, considering that the ground water level in most of these areas is high and that the population density is also great.(2) From the survey and interviews conducted, it is noteworthy that there are some households that have pour-flush toilets without waste treatment means. In this case, human waste is disposed directly into the ground underneath the toilet. An example to illustrate this case is household no. 89 of Barangay Matahimik. At present, the house owner is still saving money to upgrade the toilet facility. Residents are hesitant to invest their money in toilet facilities when they do not own the land they are occupying.(3)

For houses located on the transition and water regions, the only option left is to build makeshift overhung toilets, with the human waste directly disposed into the water or mudflat. An example of this case is house no. 236-A of Barangay Matahimik. The house is located at the end of the walkway and is approximately 200 meters from the concrete footpath on land. As shown in Figure 5.7, the overhung toilet is a separate structure made of bamboo and grass supported by stilts. The floor is made of bamboo slats with a hole at the center. Human waste is directly disposed of into the water.(4)

b. Water Supply

Water supply both for drinking and domestic use is available in the coastal communities. In the case of Barangay Matahimik and Barangay Pagkakaisa, three means are used to supply water for drinking and domestic use: tapping water from the city water lines; fetching water from the communal handpumps installed by the local government for the community; and buying water from neighbors who either have water connections from the city lines or who have handpumps.

Considering the household survey conducted in Barangay Matahimik, 15 out of the 26 household respondents, have water connection from the city waterlines. Of these 15 households, 10 have connection lines while the remaining retrieve a part of their fee for water services either by selling water to neighbors or by sharing the waterline with another household. In Barangay Pagkakaisa, 4 out of 17 households interviewed have connections to the city waterlines. The remaining households depend on fetching water from the communal handpumps or buying water from neighbors.

The city government provided access to the community to tap from the city waterlines. The water supply system of the Puerto Princesa city is managed by the Local Waterworks and Utilities Administration (LWUA). Pipe connections from the city lines are provided to the community. A household member can apply for the connection and has to pay a minimum fee of $1.80 to $2.40 per month.(5) Pipes are then suspended underneath the walkways bringing water to the houses. However, this service is limited to houses that are located on dry and transition areas.(6) To increase access to this source, and at the same time reduce the monthly expenses for this service, households with connections share the line with a neighbor or relative.

As shown in Figure 5.8, household no. 191 of Barangay Matahimik, while it is located at the end of the walkway, has access to the waterline through line sharing. In this example, the household connected a rubber hose from the water pipe of the line owner and suspended the hose underneath the houses and walkways to bring water to his house. In this set-up, the household shares the monthly fee by paying at least half of the amount.

Water pressure from the city lines varies during the day. Pressure is relatively high in early mornings and late evenings. Most often, households with connections have to collect water during these periods in large drums or containers for their use.

Some households with access to the city lines sell water to their neighbors.(7) In selling water, a faucet or rubber hose is normally installed in front of the house.

Neighbors bring their pails or containers and create a queue along the walkway. Water coming from this source is usually for drinking. As shown in Figure 5.9, a typical morning scene in the community includes waterbuying, characterized by rows of containers and pails along the walkways.(8)

Water is sold in containers with prices ranging between $0.04 to $0.08 per 20 liters. In Barangay Matahimik, a household pays approximately $0.02 for a 10 liter pail of water and $0.04 for a 20 liter container. In Barangay Pagkakaisa, the price of water is double the price of that in Barangay Matahimik. Households pay at least $0.08 for a 20-liter container. This is due to much lower water pressure in Barangay Pagkakaisa as compared to that in Barangay Matahimik.

The third source of water in the coastal communities is the communal handpumps. In Barangay Matahimik, the local government installed eight handpumps along the elevated areas of the site. At present, only four of these are functioning. Water coming from this source is consumed for drinking as well as for domestic use such as bathing, laundry, and washing.

In most cases, fetching of water is done daily. Household members fetch enough water for the consumption of the day. Since the handpumps are located on the elevated areas of the site, the household members, especially those located on the water zone, have to walk a long distance to get water.(9) Figure 5.10 shows a typical handpump provided in the community.

c. Wastewater Disposal

Wastewater from the kitchen, laundry and bathing is disposed of into the bay without treatment. The kitchen sink consists of a basin with the hole or outlet, allowing the water to spill directly outside. Laundry is normally done at the rear extension of the house beside the overhang toilet,(10) on the small balcony in front of the house,(11) or on the wooden walkways itself. A typical scene in the community is of women washing clothes in front of the houses, with a parade of clothes hanging along the sides of the walkways. Bathing is done in the extension at the back of the house beside the toilet. Others, especially children, simply bathe on their front balcony or on the walkways where laundry is done. Doing laundry and bathing in these areas is convenient for the household members since they need not bring the pails or containers of water all the way inside the house.

d. Solid Waste Disposal

Accumulation of solid wastes, mostly broken bottles, plastics and other non-biodegradable wastes, remains a big problem in the coastal communities. This has been the consequence of the improper solid waste disposal practiced by the people over the years. Natural factors such as current and wind direction also contributed to this condition. The factors influencing this problem and interventions made to solve it are discussed as follows.

In 1989, a study of problems associated with the waste disposal in the Puerto Princesa Bay was prepared under the Palawan Integrated Area Development Project (PIADP). Based on the study, the types and composition of wastes discharged in the bay include: biodegradable wastes or those that can be decomposed by natural processes in the form of papers, excreta, food leftovers, comprise about 25%; and non-biodegradable materials in the form of broken-glasses, aluminum cans and plastics comprise 75% of the total wastes. In the coastal communities, 46% of the solid wastes are thrown into the bay, 35% are burned while 16% are disposed of in open pits. Only 3% is collected by the city garbage.(12)

The problem of accumulation of solid wastes along the Puerto Princesa Bay occupied by the coastal communities is also intensified by natural environmental factors. A study of the pollution problems of the Puerto Princesa Bay identified two areas of highest waste concentration, one of which is the site of the northern coastal slums.(13) According to the study, the accumulation of the waste in these areas is influenced by tidal fluctuations, actions of river draining into the bay, wind direction and water current direction.

Under normal estuarine conditions, the flushing of water is into the river during high tide and into the open sea during low tide. Since Puerto Princesa is a protected cove, the situation is different. The study of PIADP, as shown in Figure 5.11, illustrates that the current flows into the bay during high tide and flushes out in the reverse direction during low tide. Under ideal conditions, which means without the interference of the wind and river system, the bulk of the waste discharged into the bay will be brought out into the open sea by virtue of the "in-out" movement of the currents during the tidal changes. With the action of the wind and the absence of rivers however, the wastes become concentrated at some parts of the bay.(14)

This include the northern part of the port, which is occupied by four communities of the coastal slums, namely Barangay Matahimik, Tagumpay, Seaside, and Bagong Pag-asa.

In this area, characterized by a relatively shallow depth, the absence of a river to push out the accumulated waste, and the presence of the wind for 6 months, from November to April, blowing towards the area, the waste materials cannot be carried out by the outgoing current. Hence, solid wastes continue to accumulate.

In the case of Barangay Matahimik, which is located at the coastal area with the highest waste concentration, accumulated waste is about two feet high. The pollution problem due to garbage accumulation is worsened with the disposal of untreated human waste on the shoreline from the household overhang latrines.

The city government has implemented regular collection of garbage within the whole city to resolve or minimize pollution problems. In the case of Barangay Matahimik, all households were required to collect their garbage in plastic bags or sacks and bring them to the trash bins along the main roads and pathways on land. The garbage inside the bins is then collected and brought to a dumping area along the main road for the garbage truck pickup. This organized system helped minimize the pollution problems but does not, however, solve the problem of accumulation of waste on the coasts. At present, no major action is being taken regarding the removal of these wastes from the area.

Despite this organized system for garbage collection, throwing garbage into the water is still prevalent. In the random interview of households in Barangay Matahimik, 17 out of 26 respondents collect their trash and bring them to the trash bins on the mainland for collection. Five of the respondents claim to use their garbage as fuel for cooking. Other respondents, mostly those whose houses are built on the water, claim to throw their garbage into the bay.

[ TopOfPage(); ]

5.3 Health Condition and Observed Hygienic Practices related to Sanitation and Water Supply

a. Prevailing Diseases

There is limited information on the health status of the people of the coastal slums. The response from the random household interviews conducted did not clearly indicate diseases related to poor sanitation. This aspect of the household interview cannot be used to evaluate the present health status of the community. In an interview with the employees of the City Public Health Office, among the predominant sicknesses affecting the community members, especially children, are typhoid fever and diarrhea. The 1992 Health Status Report prepared by the Health Department of the City indicates that gastro-intestinal disorders are the most prevalent sicknesses that are easily acquired through contaminated drinking water affecting all ages in the whole city of Puerto Princesa.

At present, the City Public Health cannot propose any solution to the prevailing pollution and unsanitary conditions in the community. The most they can provide are clinical services as well as health and sanitation education to the people of the coastal communities.

b. Hygienic Practices

Hygienic practices influencing the sanitation conditions in households interviewed include defecation position, anal cleaning material used, and the manner of bringing water into the house and storage of water. Inspection of the toilets in the community reveal that both squatting and sitting positions for defecating are practiced by the people. Some households, particularly those located on the elevated and drier regions of the community, have toilet seats. However, since the majority of the households have overhung toilets that consist of merely a hole in the floor, squatting is the common practice.

In terms of materials used for anal cleaning, water is used by those households with overhung toilets. This may be attributed to the fact that water is available to the community and that paper and other forms of material that can be used for anal cleaning are being discouraged from being thrown to the bay to prevent further pollution. For those households with toilets and treatment tanks, water and sometimes toilet papers are used.

The manner of bringing water into the house and storage of water are as follows. For those households with connections from the city waterlines, rubber hoses suspended underneath the houses and walkways were used. For those buying water from neighbors or fetching from the communal handpumps, water is hand carried in pails or plastic oil containers. As shown in Figure 5.12, drinking water is normally stored in plastic jars or pitchers and water for domestic and hygienic washing is stored in large metal drums or plastic pails.

The means of bringing water into the houses poses health hazards to the household members. For instance, rubber hose end connections were simply sealed with strips of cloth and the hoses have holes. Hence, water in these lines which are most often used for drinking are prone to contamination. For water carried in pails, fingers accidentally dipped into the water cause contamination as well.

Figure 5.12a and Figure 5.12b: Water is stored in plastic pails and containers and in large metal drums.

The case study illustrated that the sanitation and environmental problems in the coastal communities are due to the unsanitary means of disposing of human waste. This is amplified by the problems related to improper disposal of wastewater and solid waste.

In the two communities studied, although communal toilets have been provided, usage was not a success due to limited capacity, very poor access to users and poor maintenance. Hence, individual toilets were informally built by the people. For houses built on elevated areas, some households have septic tanks for waste disposal. For the houses within the transition area, options include the use of septic tank and direct disposal into the mudflat. The use of the septic tank in this area is questionable because of the high ground water level. The practice of directly disposing waste into the mudflat is also unsanitary because the natural flushing of excreta is obstructed by the accumulated solid waste within the area. For houses built above the water, the only option left is to build overhung toilets with the waste directly disposed of into the bay.

In the case study, the direct relation of the environmental problems to the health of the people could not be assessed well due to limited information. However, accumulated data on the health status of the people reveal diarrhea and gastro-intestinal disorders as the prevailing diseases related to sanitation and water supply.

The results of the survey from the case study presented in this chapter are then analyzed to determine significant factors to consider in the provision of sanitation technologies for the community. This analysis is presented in the next chapter.

[ TopOfPage(); ]

1. See for example the case of household no. 256 of Barangay Matahinik, Plate no.10, Appendix B .

2. See for example the case of household no. 170 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no. 7, Appendix B.

3. See Plate no.5, Appendix B .

4. See for example: Household no. 111 of Barangay Pagkakaisa, Plate no.13, Appendix B ; Household no. 114 of Barangay Pagkakaisa, Plate no. 14 Appendix B; Household no. 191 of Barangay Matahimik , Plate no. 8 Appendix B

5. All prices mentioned in the text are in Canadian Dollars. As of 1993, the exchange rate of $ 1.00 is approximately between P24.00 to P25.00 Philippine Pesos.

6. See for example the case of Household no.345 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no. 12 Appendix B.

7. See for example : Household no. 111 of Barangay Pagkakaisa, Plate no. 13, Appendix B ; Household no. 233 of Barangay Pagkakaisa, Plate no. 15 Appendix B ; Household no. 256 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no. 10 Appendix B

8. See also the cases of Household no. 114 of Barangay Pagkakaisa, Plate no. 14, Appendix B ; Household no. 236 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no. 8 Appendix B.

9. See for example the case of Household no. 131 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no. 6,Appendix B.

10. See for example the case of Household no. 191 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no.8,Appendix B.

11. See for example the case of Household no.256 of Barangay Matahimik, Plate no. 10 Appendix B.

12. Palawan Integrated Area Development Project (PIADP), Unpublished Report, 1989, p.103.

[ TopOfPage(); ]