Upcycling waste as a construction material: sulfur concrete

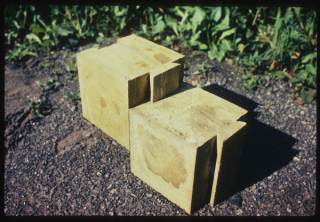

The MCHG launched with a ground-breaking idea: upcycling industrial waste into building components for low-cost housing. One of the key materials identified was sulphur, a by-product of petroleum refineries, and easily accessible in volcanic regions worldwide. Members transformed sulphur concrete into various building components such as paving blocks, bricks, tiles, and interlocking and self-aligning hollow blocks. They explored sulphur as a surface bonding and waterproofing agent.

The group experimented with new uses and applications of sulphur for low-cost housing. A concrete mixer, which was heated from the bottom, was used to combine sulphur, sand, and aggregates. The molten mixture could then be easily poured and shaped. Inspired by its many favourable attributes, including waterproofing, fast curing, strength, and availability, they cast household objects and building parts. They favoured small and interlocking components that were easy to fabricate, handle, and assemble.

Reducing buildings' operational and environmental costs: water, sanitation, and energy

The MCHG also identified household challenges of water and sanitation as one of the critical problems experienced globally by people with limited means, one that remains unresolved to this day. Driven by an ethic of environmental conservation, the Group tested low-fi techniques for collecting potable water and improving hygiene and sanitation. They embraced off-the-shelf hardware and do-it-yourself assembly techniques. Experiments in upcycling waste as a construction material were followed by new research seeking to reduce buildings’ operational and environmental costs. The items they explored ranged from composting toilets to solar stills, and from garbage bag solar water heaters to handheld water misters.

The ECOL Operation

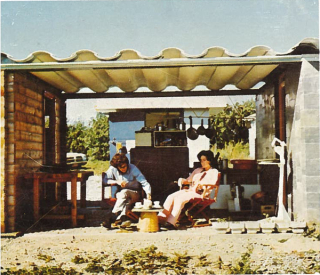

They also put sulphur concrete to the test by building several full-scale demonstration projects. The ECOL House, built on McGill University’s Macdonald Campus, was the MCHG’s first full-scale demonstration project made with sulphur. The simple design had two rooms separated by a small patio: one half tested the interlocking sulphur blocks while the other used the Pan-Abode pre-cut cedar logs. Sulphur tiles were placed as flooring, and industrial sewer pipes were cut and adapted into a low-cost, self-supporting roof. The house was visited and named “ECOL House” by Buckminster Fuller.

The MCHG also put many of its sanitation and water and energy saving experiments to the test at the ECOL House. The house attempted to resolve issues around water and power in a decentralized, small-scale, and low-cost manner; they had to “do more with less.” Rainwater was used for showering and hand-washing, and dirty wash water was converted back into drinking water using a rooftop solar still. Electricity for radios, pumps, motors, and lights was produced by a wind machine that was installed next to the house.

These influential publications introduced the Group’s mandate of developing new ways of building in ecologically responsible ways.

Subsequent Demonstration Projects

Following the construction of the ECOL house, MCHG members were involved in building full scale structures out of interlocking sulphur blocks in Canada, the United Arab Emirates, and the Philippines. In every case, the design of the sulphur block was tailored to suit local conditions and climate. In Saddle Lake in the Amiskwacīwiyiniwak region of central Alberta, they collaborated with members of the Cree Nation to build a circular community structure. In Saint-François-du-Lac, a village northeast of Montreal, they designed and built Maison Lessard, the first fully winterized building using sulphur technology.