3.1 A Brief Review

Urban renewal is not a new topic to municipality Beijing. In fact, since it was chosen to be the capital of the PRC in 1949, its inner-city had undergone redevelopment along the years.

It was estimated that in 1949, two-thirds of Beijing's residential housing were dilapidated, and 5 per cent were classified as structurally dangerous (Kwok, 1981, p.165). In order to revitalize the city and erect the new government's legitimacy, a lot of efforts were made to improve the poor living condi tions. The strategies adopted included rehabilitation of urban infrastructure and inner-city redevelop ment (Kwok, 1981, p.161). Reconstruction of Longxugou (Dragon Beard Ditch), a slum area in the heart of Beijing in the late 1950s was a noted example. Longxugou used to be the worst slum where a number of drainage ditches were used as garbage dumps. Undrained and smelly storm water often flooded the shacks. The clean-up of 200,000 tons of refuse accumulated along the ditches took three months, after which it was rebuilt as a commercial and residential neighborhood for the working class (Lalkaka, 1984).

The large portion of redevelopment in the inner-city was rehabilitation of the old housing units, which remained the chief supply of urban housing stock. During the first decade after 1949, over one million units, an equivalent of 60% of the housing stock in Beijing, were rehabilitated by the government (Kwok, 1981, p.165). In the following years, renewal projects took place in smaller scales. Redevelop ment projects were in the hands of municipal government. In order to redevelop, the government had to relocate the existing residents. The lack of available dwellings for relocation called for large invest ment besides the expenditures on land acquisition and housing demolition. With planned economy, the 'non-productive' fund in the hand of municipality was limited to large-scale redevelopment projects. Even some projects which had been planned and designed, were aborted due to exhausted resources. Heiyaochang in Taoranting area was one such case. The project occupied 3.15 hectare area of land and was planned and designed during the mid-1970s. The first phase started in 1973, and 12 years later, in 1985, finished new building totaled about 60,000 m 2, among which 50,000 m2 of housing. The project was finally aborted because of financial difficulty (Cai, 1994).

Beijing, as the capital and a national showcase, had the occasion to be granted large amount of re source to redevelop some politically significant area. In late 1977, 34 ten- to fifteen-story high apartment buildings were built along Qiansanmen avenue, the south edge of Tiananmen square, where the demolished inner-city wall used to stand. 34 buildings formed a streetscape of five kilometers long and were referred to by Beijingers as the 'new city wall' (fig. 3.1). When completed, the building were allocated by the municipal government to factories, government agencies, and schools for their em ployees. Some were reserved for residents whose houses had been demolished to make room for the renewal projects (Ma, 1981, p.233).

Beijing had built the largest number of new housing among the major cities during the period between 1949-1977. In fact, the total built-up area in 1977 was triple that in 1949. In 28 years, about 61 million m2 of space were constructed, of which 24 million were residential housing. 150 new residential dis tricts had been erected by 1977 (Ma, 1981, p.231). As a result, by 1978 the available per capita floor space in Beijing was somewhat above the national average (4.56 m2 as compared with 3.6 average) (Kirkby, 1985, p.166). Nonetheless, this number did not relieve the city from housing crisis. There were still almost one quarter of households suffering from 'severe' housing difficulties. Housing short age and over-crowding were as bad as any other large cities. According to an early 1980s' survey, 26,000 newly married couples were without their own homes; 108,000 families (around 10% of the total) where male and female children over the locally-specified age were sharing the same sleeping accommodation; 10,000 households had a per capita space of less than 2 m2 (Kirkby, 1985, p.166).

In 1978, Beijing started large-scale housing construction. Some expert believed that large-scale, inner -city renewal projects would take place within a few years because of severe overcrowding and dilapi dated living conditions in these areas (Kwok, 1981). Others supported this prediction from viewpoint of cost. McQuillan (1989, p.19) pointed out that in China's construction industry, the labor costs were much lower than material costs.1 It would be much cheaper to create new housing by rehabilitating old housing stock than by building new structures, because rehabilitation involved large amount of labor and small quantities of material. However, large-scale housing constructions were almost all located in the city periphery. The main reason was that the suburban development could avoid relocation prob lem. Further, easier land acquisition and lower administrative overhead were other favorable factors in suburban development. The old residential quarters in the inner-city were largely ignored until 1988. During this decade, investment on housing construction was at a very high level while the funds for repair and mainte nance were pitifully low. According to Zhu (1986), they accounted for only 1.78 percent of the total investment on housing construction during 1978 - 1985 in Beijing. The reason was that the preferred renewal approach continued to be demolition and reconstruction. Old residential buildings would sooner or later be cleared out to make way for new construction, thus they did not deserve any remedial efforts. After decades of deliberate negligence on repair and maintenance, the old houses had dilapi dated to very severe conditions, a large number of which were unsuitable or even dangerous for occu pation. A major effort to amend this situation could not be delayed anymore.

3.2 The living conditions in the old residential quarters

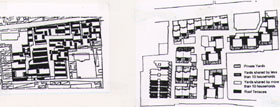

In 1949, the built area in city Beijing was only 108.9 km 2. After decades of expansion, in 1990, the built area of central urban area had reached 420 km 2, a 386% increase. From the city layout, the expan sion was radiating in concentric circles around the Old City (Yang Zhenhua, 1994) (fig. 3.2).

The Old City of Beijing occupies about 62 km2, which is the area historical preservation mainly concerns about. The layout of the Old City is a typical model of ancient Chinese capital. The city was planned primarily according to the traditional principles described in the book 'Kao Gong Ji' (Artificer's Record, late Spring & Autumn Period, 770-476 BC.), which reflected the traditional views in cosmology and code of ethics of Chinese society.

The imperial palace was located in the center of the city and the 8 km long north-south Royal Axis traversed the whole city. The street pattern was composed by orthodoxical chessboard arterial streets network and small lanes within (fig. 3.3).

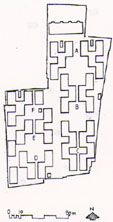

Almost without exception, the residential districts filled the gridiron street network of the city. The residential "super blocks" had an average size of about 750x750 meters (55 hectares). Rapid transportation and commercial activities were accommodated along the perimeter streets. Inside each super block, 6-step2 wide lanes called hutong3 in Chinese divided it into 44-step wide narrow strips.

Each strip was further divided into 44 by 44-step square lots, which were assumed to be possessed by one household. But most of them were sub-divided into smaller lots (Casault, 1989). This formed the so called fish-bone community tissue (fig. 3.4) (Wu, 1994). Within this frame work dwellers built their own houses in each lot. They could do so according to their means and needs without disrupting the neighborhood fabric. Traditionally, the layout of a house was decided by the economic status of the family. The house was constructed by the master builder with the participation of the owner family. In this way, houses were customized to match each family's specific needs.

With time, changes in a family's constitution and/or its economic status led to the house's transforma tion. The flexibility of changing the partition walls within the pavilion layout was ensured by the wooden column and truss structure system and the possibility of expansion could be accommodated by the resilience of the courtyard. This kind of adaptability was a main character that guaranteed the survival of the courtyard house as a prototype through history (fig. 3.5).

In 1949, 90% of the Old City area were residential quarters. There were 17.6 million m2 built space within the Old City and most were courtyard houses. Up till 1981, 4.6 million m2 had been demolished. The housing survey in the end of 1985 showed that there were 17.1 million m2 of one-story buildings at that time, almost the same as in 1949 (Jia & Liang, 1989). This fact reflected that when demolished for new redevelopment, courtyard houses had been replaced by new one-story buildings. The survey showed that at the end of 1985, one-story buildings comprised up to 45% of the total built area, of which only 9.5% was built before 1949 (Fan, 1989). According to Yu, until 1989, within the 62 km 2 of the inner city of Beijing, about 30% of the land was occupied by traditional buildings including court yard houses which totaled about 11 million m2, and housing 1.2 million people (Yu, 1989) (fig. 3.6).

Due to the lack of maintenance, many courtyard houses were in very poor condition. Three physical problems commonly existed in those dilapidated houses. First, unsafe structure, such as crumbling walls and rotting wood columns and trusses. Second, rain water accumulated in the summer time whenever there washeavy downpour, because the level of some courtyard houses was lower than the street level and also because the drainage system left from Qing and even Ming Dynasty was no longer capable of draining the water away. Finally, leaky roofs further exacerbated the former two problems. About two million m2 of the houses had been listed as 'dangerous houses' for years, but most of them were still inhabited (Yu, 1989).

Over-crowding was another serious problem. Population growth compounded simultaneously by a lag of housing supply, resulted in very high population density in the inner city. Families grew over the years but stayed in the same houses. It was quite common in these areas for a family of three genera tions to stay in one room. Lack of privacy was obvious. In extreme cases, some families had barely 2 m2 per person, just about the size of a single bed (Yu, 1989) (Fig. 3.7).

To ease these dire needs for living space, the residents resorted to building extra rooms. A 1984's survey showed that the self-built additions had substantially increased the living space (Table 3.1), consequently the FAR in these areas jumped from about 0.45 to 0.60 (Zhang Jingjin, 1992). The court yard housed all the additions and was transformed from the once sunny, delightful open space into, not uncommonly, a labyrinth (fig. 3.8). Lacking not only sunshine, many rooms could not even get natural light and ventilation. Officially these kinds of additions were prohibited, but after the 1976 earthquake, the prohibition simply could not be enforced (He Hongyu, 1990).

Lack of basic facilities was also a problem. Most of the courtyard houses did not have adequately equipped kitchens (most of the additions were used as kitchens), nor did they have showers, flushing toilets, gas lines, or central heating. Water taps usually had to be shared by several families. Trash cans and public toilets (often without flush), situated along the alleys, smelling foul all the time (Yu, 1989).

Table 3.1 The Population Density and FAR in five surveyed dilapidated residential areas

| Residential Areas | Population Density Capita/Ha | Formal Pavilions | FAR (m2/Ha) Total(including Self-builds) | Self-built/Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dongneidajie | 550 | 3624 | 5152 | 29.7 |

| Guanyuan nan | 608 | 4065 | 5715 | 28.9 |

| Guangwaidajie | 487 | 3171 | 4933 | 35.7 |

| Fuahuasi | 723 | 4118 | 5788 | 28.9 |

| Nanyingfang | 619 | 3499 | 5092 | 31.3 |

Source: Zhang Jingjin, 1992.

1). Early 1950s: floor space 2440.5 m2. A courtyard complex

2). Late 1970s: floor space 3196.5 m2, 131% of that in early 50s. A multi-household compound

3). The compound in 1987: floor space 3786.5 m2, 155% of that in early 50s. A courtyardless compound

These were the conditions in the traditional living quarters. The shanty additions, constructed with any available material, ruined the architectural grace of the old courtyard houses. The over-crowding, the poor utilities, and the incongruent-looking self-built shelters, together turned the once cozy and el egant old residential quarters into slums-like areas in the city center. It was a disgrace for the govern ment because all these conditions manifested the inadequacy of public supports.

3.3 Three Pilot Projects

The severe dilapidated and dangerous situation of urban housing existed for many years and was getting worse. A major under taking to amend this situation could not be delayed any further. The municipal government was not unwilling to respond, but, as the mayor once expressed, the government lacked the means to do so (Chen in Lu Xiaoxiang, 1991). However, years of housing reform and the growing real estate market provided new diversified resources. Within this context in 1987, four pilot projects were initiated as experiments on housing regeneration in the worst-conditioned old residential quarters.

The sites were chosen one from each of the four central city districts. Xiaohoucang in Xicheng, Ju-er hutong in Dongcheng, Dongnanyuan in Xuanwu , and Caochangtoutiao in Chongwen district. The rational was that since the municipality did not provide much financial support, each district

government was expected to explore its own ways to finance the project. This uncertainty on financial viability might explain the relatively small scale of all the four projects. Three of those four projects were completed by 1990 (except Caochangtoutiao ) (He, 1993). They were very successful in that they not only showed financial viability of the renewal projects, but explored new ap proaches on housing planning and design within the historical city center. Moreover, the political significance was also very positive.

The Sites:

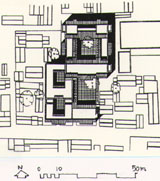

All sites of the three projects implemented by 1990 were located inside residential super blocks within the Old City, not adjacent to the perimeter large streets. The sites were small 4 compared to later projects. Xiaohoucang, the largest among the three, only covered 1.5 hectares, while the site of the first phase of Ju-er hutong was only 0.21 hectare. All the sites were chosen mainly on the merit of their advanced degree of dilapidation. The prob lems were very typically the plights described above. Over crowded Ju-er hutong had an average floor area of 7.8 m2 per capita, and with the unauthorized additions the ground coverage had increased. 56% to 83%. One third of the households could not get sunlight or even natural light all year long. Ventilation was generally very poor (Wu & Liu, 1990).

Leakage and flooding were other com mon problems. In Dongnanyuan, located in Dashila area where the population density may be one of the highest in the world, flooding was very serious in summer. The courtyards were 13 steps lower than the street level and the house interiors were two steps further down. The residents seemed to live underneath the city (Cai, 1994). Lack of basic utilities was also a common prob lem. In Ju-er hutong, 22 households in a courtyard house shared only one water tap, and the toilet was 100 meters away in the hutong (Wu & Liu, 1990).

Financing:

Each of the three projects achieved financial balance differently. The main objective of the projects was to improve the living conditions of the residents by increasing living area and providing basic necessities. Xiaohoucang and Dongnanyuan rehoused all the original residents on site, while Ju-er hutong only rehoused about one third, leaving the other two thirds to move to new residential quarters in the city periph ery or to exchange with other residents of the old city.

Xiaohoucang: although the sales price for original residents was heavily subsidized at only 280 Yuan/ m2 - not enough to cover the construction cost - only 20 households out of 269 bought their units (Huang, 1990). However, the project included an of fice building in addition to rehousing all the households, and this was sold at a market price of about 3,000 Yuan per m2, thus balancing the budget.

Ju-er hutong: initially, the project also intended to rehouse all the original residents. But due to the small scale of the parcel, it was impossible to save any land for other commercial purpose or extra housing units to sell at market price. The developer in duced the residents to move out by increasing the selling price while offering better accommodation in another area. The alternative location, Xiaoying, was near the Asian Game Village in the north of the city.

If they chose to stay, the selling price was 700 Yuan per m2 which was supposed to be shared evenly by residents and their work units. Although the price was much higher than that of Xiaohoucang, it just covered the construction cost and was still subsidized because the market price was around 3,500 Yuan per m2. In the end, 13 original households out of 42 moved back after the renewal. Through selling the other dwelling units at market price, the budget was balanced.

Dongnanyuan : financially, Dongnanyuan was a failure. Due to the location, the high population density and rehousing all the original households on site after renewal, it was impossible to have any extra floor area for market price. The situation was very similar to that in Xiaohoucang that although the selling price was highly subsidized, only 41 households, about 20% of the original, bought their dwelling units.

The rest were rented to the original residents at 0.55 Yuan per m2, a new and higher rent charge from the previous pre-renewal time. The budget was eventually subsidized by fund from local government (Cai, 1994).

Design Features:

All the three pilot projects explored new approaches to inte grate with the traditional residential context. All intended to pre serve the circulation network and the function of hutong as lively outdoor space for various activities. They all incorporated tra ditional materials in facades and architectural features like sloped roofs and intimately scaled massing to be in harmony with the traditional residential surroundings. Ju-er hutong tried to revitalize the traditional housing type in combination with modern living amenities: a shared courtyard about 15 by 13 m was the center of the two- to three-story walk-up apartment blocks on the perimeter (Wu, 1990). The idea was to keep a sense of con nection between neighbors while not diminishing the privacy of individual household and physical conditions such as sun light and ventilation. Xiaohoucang used the typical walk-up flat units, but deliberately minimized the massing to gain a more human scale. The walls along the preserved hutong were punctured occasionally by a traditionally styled gate, imparting a vernacular taste to the new structures. Both Ju-er hutong and Xiaohoucang meticulously preserved the existing trees in their layout, and the mature trees were very helpful in preserving a sense of tradition of the place. Dongnanyuan used a new walk-up housing type. The outdoor stairs provided direct and individual access from the ground and this also helped to keep the hutong lively all day long. All the three projects provided a good hierarchy of space, between the public and the private. Although no central green space was reserved, the neighborhoods were well planted. A series of activities could be accommo dated in the hierarchical spaces and no space was wasted.

Table 3.2 The Profile of the Three Pilot Projects, (source: Abramson, 1994).

Projects | Pre-Renewal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Households | %Owned Privately | Land Occupied (m2) | Built Area (m2) | |

| Ju-er Hutong Phase(I) | 44 | 2 | 2,100 | 1,672 |

| Dongnanyuan | 208 | 18 | 8,990 | 5,572 |

| Xiaohoucang | 298 | 5 | 15,000 | 8,721 |

Post-Renewal | ||||

| Number of Units | %Original Households Returned | Residential Area (m2) | Commercial and Public Area (m2) | |

| Ju-er Hutong Phase(I) | 46 | 30 | 2,760 | 0 |

| Dongnanyuan | 230 | 100 | 10,500 | 500 |

| Xiaohoucang | 350 | 100 | 19,900 | 3,100 |

The pilot projects were very successful in that they gave the municipal government the confidence to carry out housing renewal without heavy government subsidy. Thereafter in 1990, a large scale hous ing renewal program was promoted by the municipality.

3.4 Initiation of the Program

On April 30th, 1990, the Beijing municipal government issued a resolution to accelerate the pace of housing renewal, thus placing the Old and Dilapidated Housing Renewal Program in high gear. Within the second half of the same year, 37 renewal projects, as the first phase of this program, were set in motion. To date, many projects have already been completed and occupied, while others are still under construction. At the same time, new projects of Stage Two have already started.

It was interesting to note why in 1990, that particular year, the municipal government launched an urban renewal program targeting the old residential quarter. The severity of the housing problem was a prime reason, but that was not all. The following were also important considerations:

The municipal government was embarrassed by the slum-like areas in the city center . The decade-long economic boom had considerably improved the city image, the overpasses, the newly built public and commercial buildings along the wide boulevards, the high-rise apartments in the city periphery all helped to transform the old capital into a modern metropolis. But, when turning into the hutongs in the inner-city, it was like taking a trip into another age. Lacking in basic utilities, the decayed pavilions and especially the self-built additions during the late 1970s and early 1980s seemed obsolete and incongru ous in the modern streetscape. The government was determined to renew the old residential quarters, and make them fitting blocks of the modern metropolitan collage.

Vacant land in the city periphery was thought to be depleted . After decades of large-scale construction in the city periphery, the developable land assigned in the master-plan had almost been exhausted 5. If suburban development continued, it would either infringe on the preserved green space or sprawl farther away from the city. The preserved green space was the productive farmland supporting veg etable crops for the urban population, and it was also important in maintaining the urban ecological environment. If too far from the city center, development could not be sustainable because the com muting time would be unrealistically long. On the other hand, land in the inner-city was not suffi ciently utilized according to city planning authority. The dispersed one-story traditional housing was considered an inefficient use of land. Scarcity of available land was a prime motive to redevelop the inner-city.

The municipal government was finally capable of conducting such redevelopment . Ten years of large-scale housing construction had greatly improved the average living conditions of Beijingers, and relieved over-crowding in the old living quarters to a large extent, so that the relocation burden was relatively reduced. At the same time, housing reform had successfully shifted the responsibility of housing supply to work-units and local governments. Thus the municipal government could focus on helping the left-over residents6. With the financial input from district government, residents and their work-units, the municipal government was in a new position to conduct urban renewal projects which were unaffordable before7.

Based on all these factors, the municipal government initiated the Old and Dilapidated Housing Renewal Program in 1990. The sites of these projects were limited within and around the inner-city and targeted the dangerous and dilapidated parts of the old residential quarters. The financial and manage ment matters were controlled by the development enterprises. The only support the municipality of fered was a very limited fund (about 200 million Yuan) and a preferential policy - the exemption of some construction taxes on the developers.

3.5 The Scope

In initiating the renewal program, the municipal government commissioned the City Planning Institute to do a master plan for this program citywide. As the first step of the planning, a survey was done to identify the target parcels. The survey was basically an evaluation of existing housing quality, based on the criteria set by the Department of Construction. According to those criteria, housing quality was divided into five grades. The first and second were of acceptable quality, the fourth and fifth basically needed to be rebuilt, the third needed repair and renovation, either by rehabilitation or demolition -redevelopment. The renewal policy stated that if over 70% of the houses in an area were within the category of III, IV or V, and over 30% were classed in IV or V, that area was 'old and dilapidated' and needed renewal (Lü Junhua, 1994, I).

From the survey, the master plan suggested the total floor space needed to be renewed was 16.12 million m2. Among these, 10.50 million m2 were concentrated in 221 parcels, occupying 21 km 2 area of land. In those parcels, houses in class IV and V were 3.31 million m 2, about one third. Among which, 147 parcels and 80% of the area were located in the four central districts with a total floor area of 8.46 million m2 and housed 800,000 residents. The percentage of housing in class IV and V amounted to 33.5%, higher than that of the parcels in suburbs where they numbered about 22.9%. These figures showed that four central districts were the focal point of housing renewal program, both in number and in the degree of dilapidation (Zhang Zhixian, 1991).

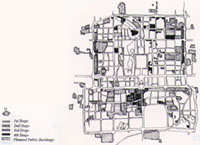

A large number of the parcels were along the demolished old city walls (now the east and west wings of the Second Ring Road, and the south edge of Qiansanmen Avenue); along the walls of the Temple of Heaven and the Temple of Xiannong; and in the gateway areas of the former city gates (fig. 3.20).

The objectives of the program were not only to improve the living conditions of the residents, but also to make way for the implementation of the city Master Plan, in order to improve the service of basic utilities. The program planned to implement phase by phase starting from the places where existing utility pipes could easily be accessed. By serendipity, most dilapidated parcels concentrated along the serviced Second Ring Road and a few thoroughfares. Thus, housing renewal in the Old City would be implemented from the perimeter radiating inwards.

The program was subdivided into four stages (fig. 3.21). Stage One included 37 projects, in which 22 were within the four urban districts, mostly on the outer side of the Second Ring Road. Stage Two had 42 parcels, mainly located along the inner side of the Second Ring Road and the south edge of Qiansanmen Avenue. The parcels were generally large and their housing conditions poor. The percent age of housing in Grade IV and V was over 30%, and the number will exceed 70% if Grade III houses were included. Those parcels could easily access basic utilities because they were adjacent to the serviced streets. Stage Three comprised of 31 parcels, located in the interior. The parcels were large and the locations were strategic for introducing utilities into the Old City area. Stage Four comprised of 25 parcels, all in the hinterland of the Old City. The parcels were smaller, remote from existing utilities, needed a large amount of investment and thus were difficult to execute (Table 3.2).

Table 3.3 The Intended Renewal Parcels in the Four Central Districts

| Before Renewal | After renewal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parcels | Land Occupied (Ha) | Built Area (M2) | Residents | Built Area (M2) | Residents | |

| Stage 1 | 22 | 166 | 790,000 | 109,500 | 2,080,000 | |

| Stage 2 | 42 | 570 | 2,730,000 | 248,000 | 6,640,000 | |

| Stage 3 | 31 | 441 | 2,560,000 | 247,000 | 5,050,000 | |

| Stage 4 | 25 | 196 | 1,160,000 | 105,500 | 1,860,000 | |

| Total | 120 | 1,373 | 7,250,000 | 710,000 | 15,630,000* | 625,000 |

*Among which, housing amounts about 11 million m2.

The four stages together comprised of 120 parcels, occupying about 14 km 2. of urban land with a population of about 710,000. Through the renewal, about 7,250,000 m2 floor space of old housing were to be demolished. Another 27 parcels of dilapidated housing areas were designated for large scale public or commercial buildings. They occupied 203 hectares of land and have 94,000 residents living in 1,210,000 m2 of old houses.

To summarize, this renewal program concentrated on the four urban districts. It was very large in scale both in terms of total area and population affected. The program would be executed phase by phase from the perimeter moving inward. The perimeter parcels were easier to tackle in terms of easier access to utilities and lower population density, which meant lower development cost on utilities and relocation. However, parcels contained within this plan were generally larger than four hectares, and comprised only two thirds of all the old and dilapidated areas that needed renewal. Many small areas of dangerous housing scattered in the old residential quarters still needed to be dealt with more specifi cally.

3.6 Ends and Means

From the beginning, improving the living conditions of residents in the dilapidated housing was clearly the main goal of the housing renewal program. The principle for the program was summarized as so called Four-, and later Five-Integrations : the housing renewal program needed to be integrated with:

1). new district development;

2). housing system reform;

3). real estate development;

4). city image preservation;

5). city infrastructure improvement;

These Five-Integrations were the co-objectives the government intended to achieve through the hous ing renewal process, where, the first three were also means to support the implementation of the pro gram. The district governments were designated the main coordinators of the program.

The goal and objectives at the initiation stage of the program can be summarized as followings:

Goal:

To improve the living conditions of residents living in dangerous and dilapidated residential areas.

Objectives:

1). To develop new districts to disperse the population density in the central area;

2). To search for new approaches in housing reform;

3). To establish a self-sustained real estate industry;

4). To improve the appearances of the Old City , transform the city into a modern metropolis while keeping the traditional characteristics;

5). To improve urban infrastructure in the Old City;

6). To revise land use in the Old City;

Although the prime goal was clearly to improve living conditions of the residents in dilapidated areas, there were more diverse objectives which fell into three directions: to build a self-contained housing industry (2 & 3); to implement the city Master Plan (1, 5 & 6); and to assist in the historical preservation of the city (4). The most difficult problem of the housing renewal program was the scarcity of funds (Lu Xiaoxiang, 1991, I). The strategy, therefore, was mainly focused on economic viability. In order to reduce the population in the central area and revise land use, housing renewal needed to be in conjunction with the new district development in that the program needed accommodation in the periphery area to relocate the original residents. But more importantly, the new district development was expected to cross-subsidize the renewal projects. This help could be direct cash input within the same development enterprise, such as using the profit from new development to balance the deficit in the renewal project, or it could also be between different developers, such as providing the relocation accommodation at discounted prices (Lu Xiaoxiang, 1991, I).

In the housing reform, housing responsibility had decentralized from state to municipality, and further to district government. The district government in this case shared the burden with work-units and residents. As discussed in the previous chapter, this is the direction of housing reform: to let housing become individual households' own business.

The integration with real estate development was based on the same concern for financial viability. If a self-sustained real estate industry existed, then the subsidy from the government would no longer be needed. The possibility of this integration relied on the high land value in the central area. By common business sense, in high valued land, housing development needed to be of high quality and also trans acted at higher prices, and the profit thus gained would finance the relocation of the original residents, in this case, most probably to the outskirts.

As mentioned above, a prime reason to initiate the housing renewal program was that the old residen tial quarters had become a disgrace to the capital. Housing renewal in the Old City provided an oppor tunity to implement the city's Master Plan, which aimed to guide the city towards a modern metropo lis. And only through a thorough renewal could the basic infrastructure be updated. This is where the renewal program integrates with urban infrastructure improvement.

Among the objectives of the renewal program, the most ambiguous and thorny issue was city image preservation. Debates on this topic had lasted many years, among professionals, politicians and then the public. The subjects ranged from 'Does the city image deserve to be protected? ' to 'what to protect?' and 'how to protect ?'. This by itself showed a progress in the understanding of the issue. The necessity of integration with city image preservation for renewal projects marked an awareness of the importance of historical preservation.

3.7 The Players and Their Roles in the Renewal Program

The main players involved in the regeneration process in terms of program preparation, project imple mentation and utilization, are the municipal and local governments, various development and construction enterprises, designers including planners and architects, construction companies, and the original residents , the in-coming households as well as their work-units, which are actually the main consumers of the housing market (He Hongyu, 1993) (fig. 3.22).

As stressed above, the district governments were appointed the main coordinators of the renewal pro cess. They decided the location and size of renewal parcels; choose the form of redevelopment in terms of relocation, land usage and building types; and took responsibility for management after occupancy (Lü Junhua, 1993, II). The municipal government did not want to finance the program, but monitored the process closely through its branch bureaus. They were involved in the whole process from initia tion, to examining and to approving the detailed planning and design.

The development and construction enterprises were companies affiliated to the two levels of govern ment (He Hongyu, 1993). At the beginning, district government made the decisions at the preparatory stage and was responsible in case of financial deficit. Later, following further economic reform and the real estate boom, although still carrying the governments' imprimatur ( Lü Junhua, 1993, II), developers were becoming independent, self-supporting business enterprises. Profit-making became the prior ity. More and more they assumed responsibility for the whole development process, and the govern ments stepped back from the stage and were only in charge of setting the regulations and, sharing profits.

Professionals8 were the designers in institutes of urban planning and architectural design. Renewal projects were generally planned and designed by various architectural design institutes under the de tailed planning guidelines drawn by City Planning Institute of Beijing. Like any other profit-oriented developments, the specific demands of developers restricted the creativity and performance of the project designers.

Generally speaking, the construction companies involved in housing renewal were low profile companies lacking in skilled labors and modern tools. Although in a few cases like Ju-er hutong, the aspiration of builders fine-tuned the design. The construction process was supervised by a project manager who coordinated with the developer, the project designers including architect and engineers, and ex perts from municipal quality control bureau.

The consumers were composed of three categories, the original residents, the new comers and their work-units. Many social critics had pointed out that the original residents were often in a very disad vantaged position in the renewal process. They had very few options: either to stay in low quality rehousing units on site or to move to the far peripheral settlements. Now that the renewal program would affect 40% of Beijingers living in the central urban area, they ought to have a more active role. The work-units of the newcomers were the most important consumers of the housing market. They directly funded the relocation of original residents (He Hongyu, 1993). However, being the end users, their needs were not sufficiently attended to justify the price they paid.

The renewal program touches upon the political, economic, socio-cultural, environmental and techni cal aspects of society, on which each sector has its own expectation and concerns, which are often mutually conflicting. In this sense, housing renewal is a compromise among various interest groups. Next chapter will evaluate the program through case studies, in terms of identifying problems in the projects already implemented, and to discern the direction in the more recent proposed projects. Effort will also be made to identify the role each sector played in the process and the key issues of this program, which relate to the viability of projects in future stages.

1 A 1981 estimate showed that of 80% of total building production costs, labor accounted for only 7%, machinery 4%, miscellaneous 2%, and building materials 67%. The other 20% was for the administrative expenditures and taxes (McQuillan, 1985, p.19).

2 A measure used in ancient China.

3 Hutong was an Mongolian expression meaning "well".

4 There was a regulation that the parcels needed to be at least four hectares in size if it was for housing construction within the old city. The regulation was conceived to protect the city image because a lot of sporadic buildings had damaged the harmony of the area and infringed the master plan. This will be further discussed in Chapter Four.

5 In deed, many pieces of land allocated to individual work-units were not sufficiently used, and some factories which occupied large areas in the zone inbetween the Second and Third Ring Road were about to remove to far suburb. Thus the near suburb still had a big potential to be redeveloped. This will be further discussed in Chapter Five.

6 The remaining residents lived either in their private houses or in publicly owned houses. Those who lived in publicly owned houses worked for poor or small work units and/or had less powerful status in their work units. For them, it was very difficult to get access to the new developments.

7 There were about 400,000 households living in the dilapidated courtyard houses. To improve their housing standard to the average level of other communities, tens of billions of Yuan was needed (Huang Hui, 1991).

8 Actually, many government officials of various bureaus pertaining to city planning and housing management, were also experts in the field of city planning and architectural design, but here they represented the governments.

[ TopOfPage(); ]